¶ Cell Stem Cell

¶ Generation of human nucleus basalis organoids with functional nbM-cortical cholinergic projections in transplanted assembloids

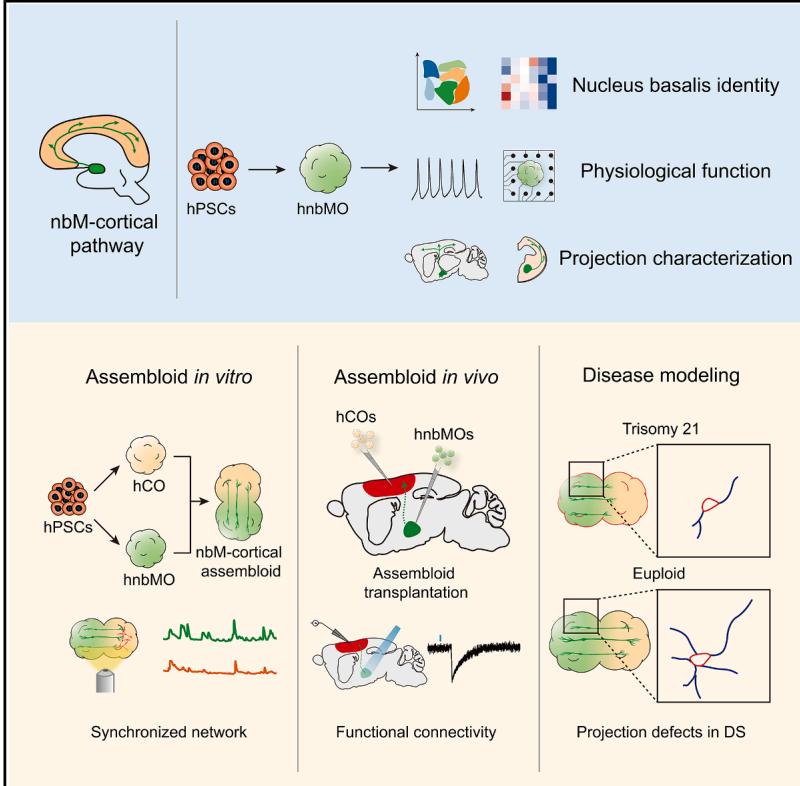

Graphical abstract

¶ Authors

Da Wang, Xinyue Zhang, Xiao-Yan Tang, …, Qing Cheng, Xing Guo, Yan Liu

¶ Correspondence

ydong@tyxx.ecnu.edu.cn (Y.D.), chengq@njmu.edu.cn (Q.C.), guox@njmu.edu.cn (X.G.), yanliu@njmu.edu.cn (Y.L.)

¶ In brief

The nucleus basalis of Meynert (nbM) regulates cortical function and cognition. Liu and colleagues report a method for creating human nbM organoids (hnbMOs) containing cholinergic projection neurons that form functional connections with the cortex. This work provides a model to investigate nbM circuits and cholinergic dysfunction in neurological disorders.

¶ Highlights

• Human nbM organoids generated from hPSCs recapitulate nucleus-specific identity

• hnbMOs establish long projection and functional connectivity with hCOs in vitro

• Assembloid transplantation formed the functional nbMcortical cholinergic pathway

• nbM-cortical assembloids model projection deficits in Down syndrome

¶ Generation of human nucleus basalis organoids with functional nbM-cortical cholinergic projections in transplanted assembloids

Da Wang,1,2,7 Xinyue Zhang,2,7 Xiao-Yan Tang,1,7 Yixia Gan,3,7 Hanwen Yu,1,7 Shanshan Wu,1,2 Yuan Hong,1

Mengdan Tao,1 Chu Chu,1 Xiaoxuan Qi,4 Hao Hu,2 Yimin Zhu,1 Wanying Zhu,1 Xiao Han,1 Min Xu,1 Yi Dong,3, *

Qing Cheng,4, * Xing Guo,2,5, * and Yan Liu1,2,6,8, *

1Institute for Stem Cell and Neural Regeneration, School of Pharmacy, Nanjing Medical University, Nanjing 211166, China

2State Key Laboratory of Reproductive Medicine and Offspring Health, Nanjing Medical University, Nanjing 211166, China

3Key Laboratory of Adolescent Health Assessment and Exercise Intervention of Ministry of Education, East China Normal University,

Shanghai 200241, China

4Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Women’s Hospital of Nanjing Medical University, Nanjing Women and Children’s Healthcare

Hospital, Nanjing 210004, China

5Department of Neurobiology, School of Basic Medical Sciences, Nanjing Medical University, Nanjing 211166, China

6Jiangsu Province Innovation Center for Brain-Inspired Intelligence Technology, Nanjing 210029, China

7These authors contributed equally

8Lead contact

*Correspondence: ydong@tyxx.ecnu.edu.cn (Y.D.), chengq@njmu.edu.cn (Q.C.), guox@njmu.edu.cn (X.G.), yanliu@njmu.edu.cn (Y.L.)

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.stem.2025.10.004

¶ SUMMARY

The nucleus basalis of Meynert (nbM), the major cholinergic output of the basal forebrain, regulates cortical modulation, learning, and memory. Dysfunction of the nbM-cortical cholinergic pathway is implicated in neurodegenerative and neurodevelopmental disorders, including Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and Down syndrome (DS). Here, we generated human nbM organoids (hnbMOs) from human pluripotent stem cells (hPSCs) containing functional cholinergic projection neurons. Then we reconstructed long-distance cholinergic projections from nbM to the cortex by co-culturing hnbMOs with human fetal brains and transplanting hnbMOs into immunodeficient mice. We further established nbM-cortical assembloids by fusing hnbMOs with human cortical organoids (hCOs). We also established a human-specific cholinergic projection system in transplanted assembloids. Using viral tracing and functional assays, we validated that cholinergic neurons send projections into hCOs and form synaptic connections. Moreover, we captured projection deficits in DS-derived assembloids, demonstrating the utility of this model for studying nbM-related neural circuits and neurological disorders.

¶ INTRODUCTION

The nucleus basalis, also known as the nucleus basalis of Meynert (nbM), mainly originates from the medial ganglionic eminence (MGE) and is considered one of the primary cholinergic outputs of the basal forebrain. It has been shown to dynamically modulate cortical activity and plays a critical role in learning and memory processes.1,2 Dysfunction of the cholinergic pathway from the basal forebrain to the cortex is implicated in neurological disorders such as Alzheimer’s disease and Down syndrome (DS), which is associated with cognitive impairment.3–5 Human cholinergic neurons (CHNs) derived from human pluripotent stem cells (hPSCs) provide powerful tools to study CHN-associated diseases and cell therapy.6–8 Previous studies reported the generation of two-dimensional (2D) human basal forebrain cholinergic neurons (BFCNs), which were limited to accurately replicate the spatial organization, cellular diversity, and crosstalk between different brain regions.

Brain organoids derived from hPSCs in three-dimensional (3D) culture recapitulate the developmental processes and physiological functions of the human brain.9–12 Previous studies have established region-specific brain organoids, including the cerebral cortex, thalamus (TH), cerebellum, etc.13–15 Afterward, assembloids fused with diverse region-specific organoids have become a model of crosstalk between different brain regions in vitro. 16–19 Meanwhile, animal models transplanted with human brain organoids provide a powerful platform for investigating the unique characteristics of human neural cells and the pathophysiology of neural circuits in vivo. 20,21 Although several nucleusspecific organoids have been established,22–24 the generation of organoids or assembloids containing BFCNs has not been reported. Therefore, a better model to recapitulate the human nucleus basalis and cholinergic projections in the nbM-cortical pathway is desired.

Here, we developed an approach for differentiating hPSCs into nbM organoids that encompassed functional CHNs in vitro and in vivo. Then we fused human nbM organoids (hnbMOs) with human cortical organoids (hCOs) to form nbM-cortical assembloids. We verified that CHNs project to hCOs and form functional connectivity in nbM-cortical assembloids. An innovative dual-transplantation approach was developed by transplanting corresponding organoids into the cortex and nbM region, thereby establishing a complete human cholinergic projection system. Furthermore, we identified the defects in the projection of CHNs in assembloids derived from DS induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs). Our work establishes a new approach for the study of neurological disorders associated with the nbMcortical CHN circuit.

¶ RESULTS

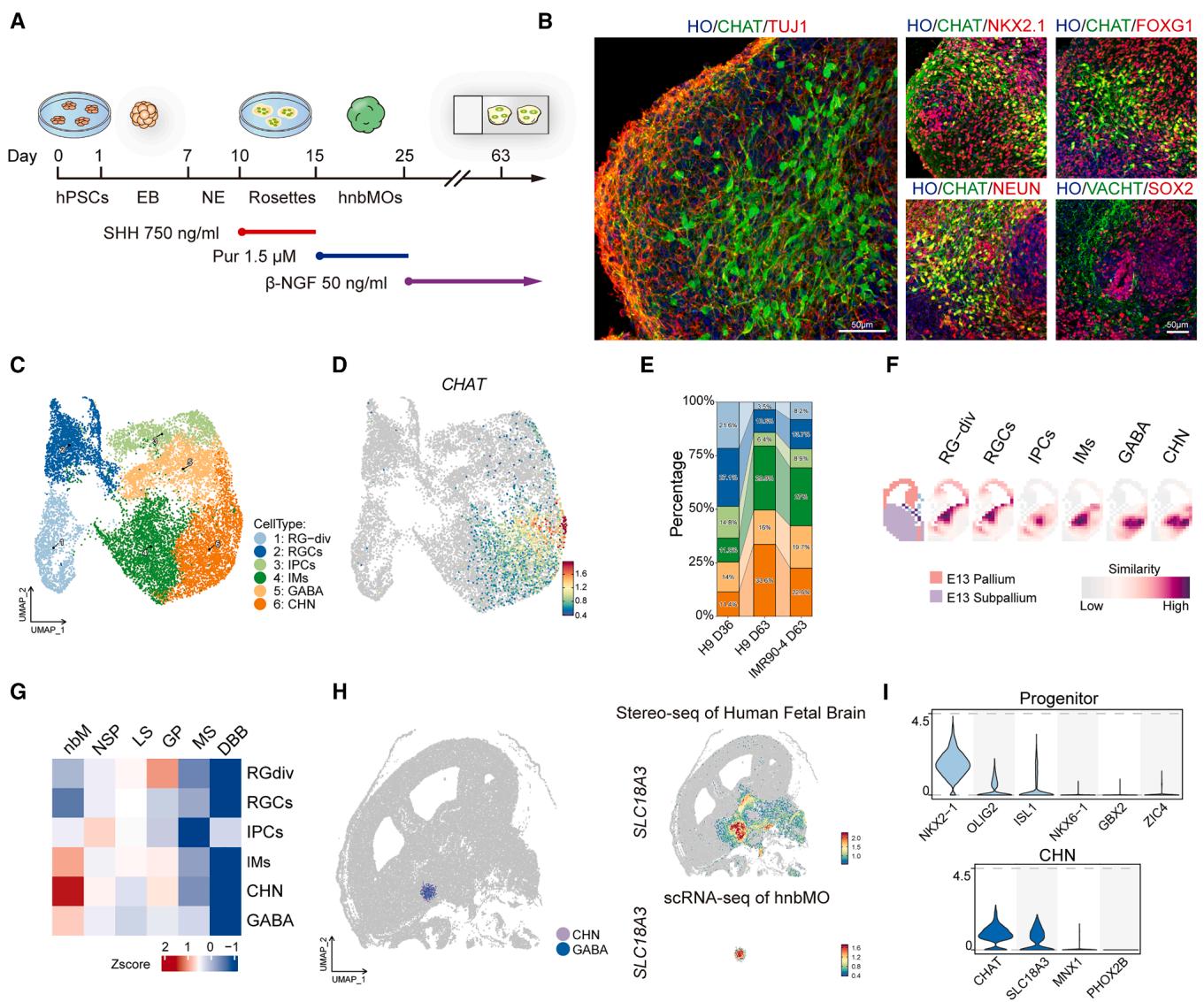

¶ Generation of hnbMOs from hPSCs

To generate hnbMOs in vitro, we established a differentiation protocol optimized from the 2D BFCNs culture strategy we previously reported (Figure 1A).6 Early treatment with high concentrations of sonic hedgehog (SHH) and combination with the SHH pathway agonist purmorphamine (Pur) enable the generation of MGE progenitor cells, which could develop into the nucleus basalis. 25,26 For the promotion of further differentiation of CHNs in the nucleus basalis, nerve growth factor (NGF) was subsequently added.2 To determine the optimal differentiation conditions for hnbMOs, we performed SHH dose-dependent experiments to ventralize the neural tube at the neuroepithelial stage (day 10). The MGE progenitor marker NKX2.1 expression in organoids was elevated with increasing SHH concentration (Figure S1A).28–31 At the treatment of SHH, the organoids exhibited the highest expression of NKX2.1 in total cells at day 36 and showed the highest expression of the CHN marker CHAT in NEUN+ cells at day 63 (Figure S1B; Video S1). We also identified abundant expression of forebrain marker FOXG1 and neuronal marker TUJ1 in hnbMOs at day 63 (Figures 1B and S1C). Furthermore, we also validated the expression of the typical CHN marker, vesicular acetylcholine (ACh) transporter (VACHT), which is responsible for packaging ACh into vesicles and was expressed in of neurons (Figures 1B, S1D, and S1E).

To validate the regional characterization and lineage specialization of hnbMOs, we performed single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) on hnbMOs derived from human embryonic stem cells (hESCs) (H9) at two differentiated time points (day 36 and 63) and from iPSCs (IMR90-4) at day 63, capturing a total of 14,245 cells. Uniform manifold approximation and projection (UMAP) revealed the identity of 6 cell types: dividing radial glial cells (RG-div), radial glial cells (RGCs), intermediate progenitor cells (IPCs), immature neurons (IMs), GABAergic neurons (GABAs), and CHNs (Figures 1C, S1F, and S1G). The CHN-marker gene CHAT is specifically highly expressed in CHNs (Figure 1D). From day 36 to 63, cell-type abundance analysis showed that the percentage of progenitor cells (RG-div, RGCs, and IPCs) decreased from to , while the percentage of cells in GABA and CHN clusters increased from to , suggesting a developmental transition from proliferative progenitors to differentiated GABAs and CHNs (Figures 1E and S1H). CHNs, identified by CHAT or SLC18A3 expression, and GABAs, marked by GAD2, represented the two major neuronal types in hnbMOs (Figures 1D and S1I). Pseudotime trajectory analysis suggested that these two populations may follow distinct differentiation pathways (Figures S1J and S1K). Notably, scRNA-seq analysis of H9- derived hnbMOs revealed that of cells expressed the CHN-marker CHAT, while expressed the mature neuron-marker RBFOX3 at day 63 (Figure S1L). hnbMOs derived from the human iPSC (hiPSC) line IMR90-4 demonstrated similar lineage development and an enriched production of and CHAT+ cells, indicating the reliability of hnbMO generation across different hPSC lines (Figures 1E, S1M, and S1N). To verify the regional identity of hnbMOs, we spatially mapped the scRNA-seq data of hnbMOs onto mouse in situ hybridization data from the Allen Brain Atlas by applying VoxHunt32 and found hnbMOs exhibited a higher correlation with the subpallium of the mouse forebrain compared with other regions. Furthermore, we found that RGCs in hnbMOs showed the high-scaled correlation with the ventricular zone (VZ) region of the mouse MGE when analyzing the atlas corresponding to the different cell types (Figure 1F). We next compared the transcriptomic signatures of hnbMOs with those of human fetal brain regions using the BrainSpan Atlas of the Developing Human Brain.33 Remarkably, at day 36, hnbMOs exhibited the highest scaled correlation with MGE of the human fetal brain in 8–9 postconceptional weeks (PCW) (Figure S1O). Furthermore, transcriptomic analysis revealed that both CHN and GABA clusters of hnbMOs at day 63 exhibited the highest transcriptomic similarity to the nbM of the human fetal brain at 21 PCW, with much lower similarity to other MGE-derived nuclei, such as the medial septal (MS) nucleus and diagonal band of Broca (DBB) (Figure 1G). Moreover, we mapped the CHN and GABA clusters from hnbMO scRNA-seq data onto the spatial transcriptomic dataset of the human gestational weeks (GW) 16 fetal brain and multiplexed error-robust fluorescence in situ hybridization (MERFISH) data from the adult mouse brain.34,35 These results demonstrated that both clusters showed specifically high similarity to the nbM region in both human and mouse brains (Figures 1H and S1P).

To further validate the transcriptomic characteristics of nucleus basalis identity in hnbMOs, we observed that their progenitor cells exhibited robust expression of NKX2-1, OLIG2, and ISL1, key transcription factors crucial for the development of CHNs in the basal forebrain.25,30,36–38 By contrast, these cells showed negligible expression of NKX6-1 and GBX2 (Figure 1I), which are primarily associated with spinal motor neurons and striatal cholinergic precursors.39 –41 ZIC4, a transcription factor specifically expressed in the medial septum but not in the nbM,42,43 was scarcely detected in the precursor cells of hnbMOs (Figure 1I), indicating that hnbMOs are regionally distinct from the medial septum. Additionally, mature CHNs in hnbMOs barely expressed MNX1 and PHOX2B, which are characteristic of spinal CHNs (Figure 1I).44,45 These results indicated the specific MGE lineage characteristics and nbM identity of hnbMOs at the transcriptional level.

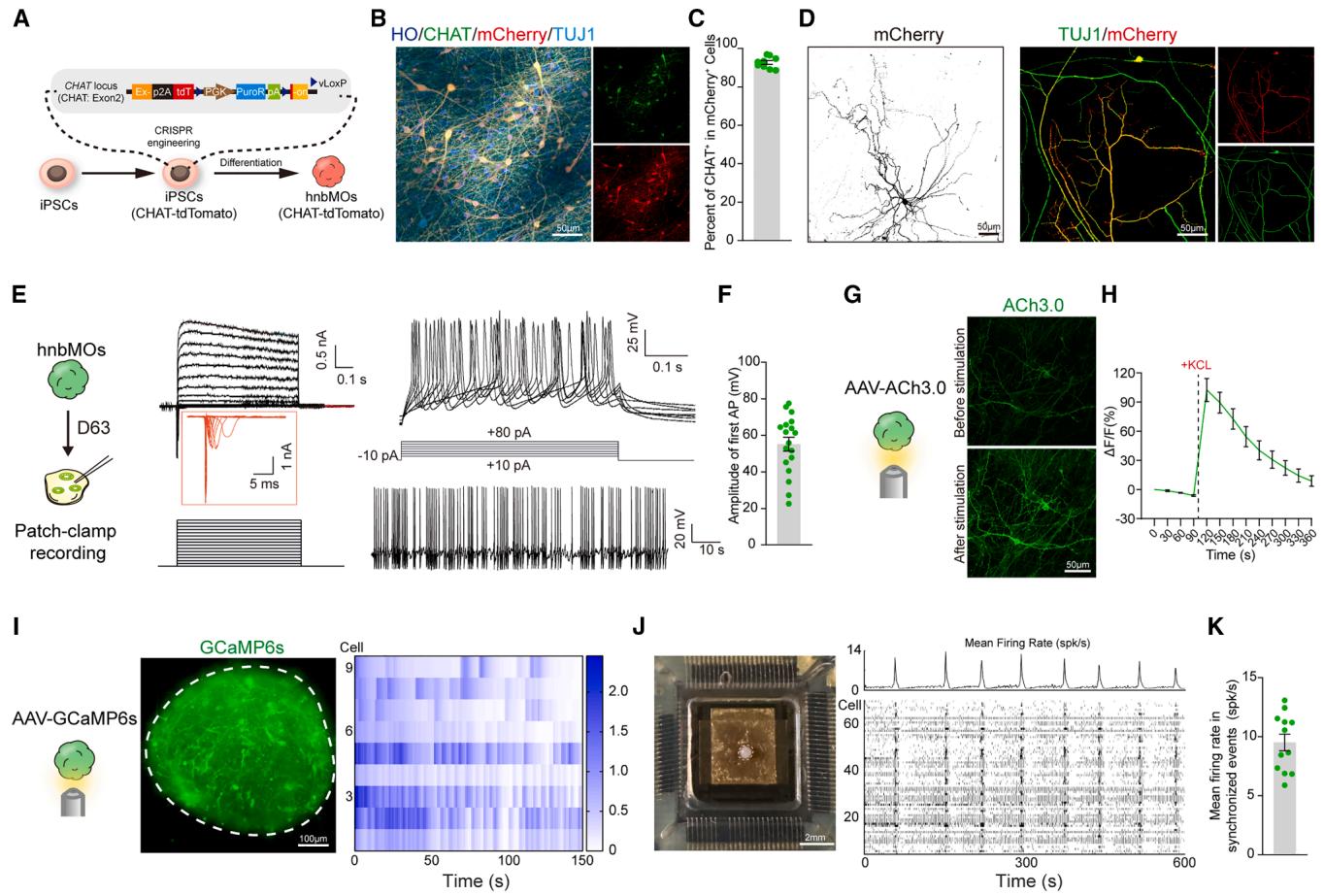

¶ Morphological and functional maturation of hnbMOs

To assess the morphological and functional maturation of hnbMOs, we first sought to establish a reliable approach for specifically identifying hPSC-derived CHNs. To this end, we built a CHAT report line by inserting the fluorescent protein tdTomato into the CHAT locus (CHAT-tdT hPSCs) (Figure 2A). We used the anti-mCherry antibody to label the red fluorescent protein tdTomato, which shares high sequence homology with mCherry. We observed that of mCherry+ cells were CHAT+ CHNs after differentiating CHAT-tdT hPSCs into hnbMOs (Figures 2B and 2C). Since BFCNs utilize massive neuritic arbors to innervate large areas of the cerebral cortex,46 we observed that CHNs exhibited a typical projection neuron morphology with long neurites and dendritic spines at day 100 (Figure 2D).

Figure 1. Generation of hnbMOs from hPSCs

(A) Schematic showing the differentiation condition for hnbMOs. hPSCs, human pluripotent stem cells; EB, embryoid body; NE, neuroepithelial cell; SHH, sonic hedgehog; Pur, purmorphamine; -NGF, beta nerve growth factor.

(B) Immunostaining of hnbMOs for CHAT, TUJ1, NKX2.1, FOXG1, NEUN, SOX2, and VACHT at day 63 (scale bar, .

© UMAP of cell types in hnbMOs from H9 (day 36, day 63) and IMR90-4 (day 63).

(D) Feature plots showing the expression of the CHAT gene in hnbMOs.

(E) Percentage of all cell types in the scRNA-seq data split by groups in hnbMOs.

(F) VoxHunt mapping of hnbMO clusters onto the E13 mouse brain (Allen Brain Atlas).

(G) Heatmap showing the gene set score analysis between different human MGE-derived nuclei (21 PCW) and various cell types in hnbMOs. nbM, nucleus basalis of Meynert; NSP, nucleus subputaminalis; LS, lateral septum; GP, globus pallidus; MS, medial septum; DBB, diagonal band of Broca.

(H) Spatial projection of hnbMO-derived CHN and GABA onto the Stereo-seq spatial transcriptomic map of human GW16 fetal brain (left). Spatial expression of SLC18A3 in Stereo-seq data of the human fetal brain (right top) and scRNA-seq data of hnbMOs (right bottom).

(I) Violin plots of marker genes in progenitor (day 36) and CHN (day 63) clusters of hnbMOs.

See also Figure S1, Table S1, and Video S1.

To evaluate the physiological function, we detected the electrophysiological activity of hnbMOs at day 63. We detected depolarization-evoked sodium and fast potassium currents, together with both evoked and spontaneous action potentials, confirming their electrophysiological activity (Figures 2E and 2F). The release of ACh transmitters is also a critical physiological process in CHNs; thus, we utilized the previously reported ACh biosensor (ACh3.0).47 Live-cell imaging analysis detected the presence of the sensor, as indicated by GFP expression, in hnbMOs-derived neurons (Figure 2G). The GFP signal intensity significantly increased upon KCl stimulation, demonstrating the functional release of ACh in hnbMOs (Figures 2G and 2H).

Figure 2. Morphological and functional maturation of CHNs in hnbMO

(A) Schematic of experimental design for generating CHAT reporter cell line.

(B) Representative images of CHAT and mCherry in hnbMOs differentiated from the CHAT reporter cell line at day 45 (scale bar, .

© Scatterplots showing the quantification of cells in mCherry+ cells in CHAT reporter hnbMOs (scale bar, ).

(D) Immunostaining of neurite for mCherry and TUJ1 in CHNs derived from CHAT reporter hnbMOs at day 100 (scale bar, ).

(E) Whole-cell patch-clamp recording and representative membrane response of , current peak, and APs of CHAT-tdTomato neurons in hnbMOs at day 63. (F) Scatterplots showing the amplitude of the first AP in hnbMOs. The data were obtained from 3 independent biological experiments. cells from 6 organoids; mean SEM.

(G) Representative images of expression in hnbMOs before and after adding KCl ) at day 60 (scale bar, ).

(H) Representative ΔF/F traces showing ACh3.0 fluorescence responses in hnbMOs before and after adding KCl ). The data were obtained from 3 independent biological experiments. organoids; mean SEM.

(I) Calcium imaging of hnbMOs neurons expressing the calcium indicator GCaMP6s at day 80 of differentiation. Heatmap showing of GCamP6s signal from 9 cells. Imaging was repeated in hnbMOs from 3 independent differentiation experiments with similar results (scale bar, ).

(J) MEA assay in hnbMOs at day 120. Bright field of hnbMOs cultured using the HD-MEA Accura Chip (scale bar, , left), mean firing rate in the hnbMO area, and raster plot of neural network activity from 74 cells (right).

(K) Scatterplots showing mean firing rate in synchronized events from hnbMOs. The data were obtained from 3 independent biological experiments. organoids; mean SEM.

See also Videos S2 and S3.

Synchronized activity of neural networks is considered a characteristic of maturity in organoids. To assess network activity, we imaged GCaMP6s-expressing hnbMOs at day 80 and observed multiple synchronized spontaneous calcium events (Figure 2I; Video S2). To evaluate the electrophysiological synchronization activity of hnbMOs, the high-density 3D microelectrode array (HD-MEA) recordings at day 120 detected spontaneous spikes and network-level synchronization in hnbMOs (Figures 2J and 2K; Video S3). In summary, the calcium imaging and microelectrode array (MEA) recordings showed neural synchronization of hnbMOs.

Taken together, these data demonstrated that hnbMOs exhibited both morphological and functional maturation characteristic of BFCNs.

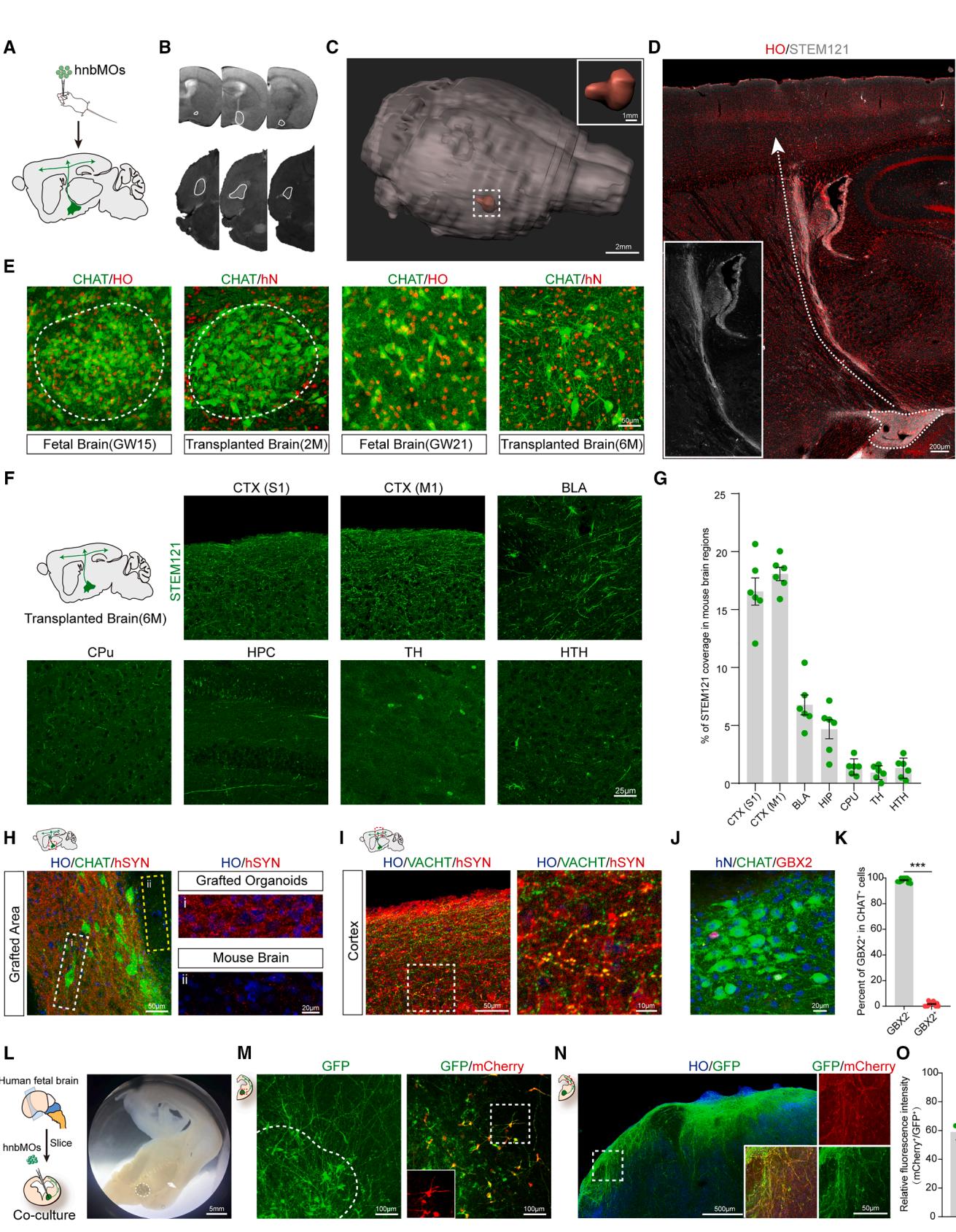

Figure 3. Characterization of cholinergic projection in hnbMOs

(A) Schematic of the identification transplantation experimental design. hnbMOs are transplanted at day 37 of differentiation into the nbM of SCID beige mice.

(B) Coronal and horizontal view T2-weighted MRI images showing grafted hnbMOs in the nbM at 2 months post-transplantation.

© 3D volume reconstructions using MRI images of mouse brain at 2 months post-transplantation (scale bar, ).

(D) Overview of projection pathways from grafted hnbMOs in the transplanted mouse brain at 6 months post-transplantation (scale bar, 200 μm).

(E) Immunostaining of CHAT+ neurons in the nbM of GW15 human fetal brain and GW21 human fetal brain, grafted hnbMOs at 2 months post-transplantation and

6 months post-transplantation (scale bar, 50 μm).

(F) Schematic of projection tracing from grafted hnbMOs in sagittal sections. Representative images of STEM121⁺ projections in multiple brain regions at

6 months post-transplantation. Primary somatosensory cortex (S1), primary motor cortex (M1), basolateral amygdala (BLA), caudate putamen (CPu), hippocampus (HPC), thalamus (TH), and hypothalamic region (HRH) (scale bar, 25 μm).

(G) Quantification of percentage of STEM121 fluorescence coverage in the transplanted mouse brain. The data were obtained from 3 independent biological

experiments. n = 6 mice; mean ± SEM.

(H) Representative images of CHAT and hSYN in grafted hnbMOs and surrounding mouse brain tissue (left); (Gi) for grafted organoids and (Gii) for mouse brain

(scale bar, 50 μm, left; 20 μm, right).

(I) Representative images of VACHT and hSYN in mouse cortex (scale bar, 50 μm, left; 10 μm, right).

(J) Representative images of GBX2 and hN in CHAT+ neurons of grafted hnbMOs at 2 months post-transplantation (scale bar, 20 μm).

(K) Scatterplots with the bar showing the percentage of GBX2− and GBX2+ cells in CHAT+ neurons of grafted hnbMOs. The data were obtained from 3 independent biological experiments. n = 6 mice; 2 random slices were quantified for each mouse; two-tailed unpaired t test; mean ± SEM. ***p < 0.001.

(L and M) Bright field of hnbMOs cultured with human fetal brain slice (scale bar, 5 mm) and representative images of mCherry+ CHN coimmunostaining with GFP

in co-cultured hnbMOs (scale bar, 100 μm).

(N) Representative images of mCherry+ cholinergic projections coimmunostaining with GFP in the cortex of a fetal brain slice (scale bar, 500 μm, left; 50 μm, right).

(O) Scatterplots showing the percentage of relative fluorescence intensity (mCherry+/GFP+) in human fetal cortex. The data were obtained from 3 independent

biological experiments. n = 6 slices from 3 fetal brains; 2 slices were quantified for each brain; mean ± SEM.

See also Figure S2.

¶ Characterization of hnbMOs projections in transplanted mice and co-cultured brain slices

Cholinergic projection neurons in the nucleus basalis innervate the cortex with long, highly branched, and elaborate axonal arbors.48 Our work has demonstrated that CHNs in hnbMOs showed typical projection neuron morphology. However, the lack of specific factors, such as mechanical structure and signaling, has limited the targeted axonal growth of CHNs in vitro—maintained organoids. The transplantation of organoids overcomes these limitations and provides a model for maturation and axon guidance of in vivo human neural circuits.20,21,49 To establish the human nbM-cortical cholinergic pathway in vivo, we transplanted hnbMOs into the nbM region of severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID) Beige mouse brains (Figure 3A). We performed T2-weighted MRI on mice at 2 months post-transplantation to visualize the localization of organoids in living mice (Figure 3B). After applying 3D reconstruction, we found that the grafted organoid was accurately localized in the nucleus basalis in the host brain (Figure 3C). We next assessed the cellular identity characteristics of grafted organoids by immunofluorescence at 2 months post-transplantation. Grafted human cells were identified by hN and STEM121 expression (Figures 3D, 3E, and S2A–S2D). Immunostainings revealed human grafted cells that co-expressed CHAT , FOXG1 , NKX2.1 , and OLIG2 with hN (Figure S2B). At 6 months post-transplantation, approximately -long-distance projection bundles in the dorsolateral pathway were observed to project from the grafted organoids into the host cortex (Figure 3D). Abundant human-derived fibers were observed in the primary somatosensory cortex (S1), primary motor cortex (M1), and basolateral amygdala (BLA). By contrast, only sparse projections were detected in the caudate putamen (CPu) and hippocampus (HPC), with minimal signals observed in the TH and hypothalamic region (HRH) (Figures 3F and 3G). These results suggest that the grafted nbMOs established human-derived projections in the host brain, which recapitulated the characteristic cholinergic projection pattern of the nucleus basalis in vivo. 50

We next examined the developmental pattern of grafted CHNs from 2 to 6 months after transplantation (Figure 3E). At 2 months post-transplantation, groups of CHNs in the grafted organoid formed a nest-like pattern, similar to the primitive CHNs generated in the human fetal brain at GW15. At 6 months post-transplantation, the primitive CHNs in the nest-like structure gradually dispersed over time to form more abundant projection neurons, which is similar to a previously reported article studying MGE development in the human fetal brain.51 Meanwhile, the expression of enriched human synapses in transplanted organoids was also observed (Figure 3H). Furthermore, confocal microscopy analysis revealed that large numbers of STEM fibers projected into the mouse cortex, closely apposed the processes of mouse pyramidal neurons, and also expressed human-specific synaptophysin (SYP) (Figure 3I). To further verify the identity of the transplanted hnbMOs, we observed widespread expression of the human nuclear marker (hN) among Hoechst+ nuclei and the presence of ACh receptors among cells in the grafted region (Figures S2E and S2F). We also detected human-derived GABA, including the GABAergic subtype marked by calretinin (CR) (Figure S2G), allowing further characterization of the inhibitory neuronal diversity in the grafts. We found that nearly all CHNs in the grafted hnbMOs were (Figures 3J and 3K), which excludes the expression of cholinergic interneurons. The results demonstrated that CHNs in grafted organoids maintain their projection neuron identity and project long distances to the cortex.

To better understand the projection of CHNs in hnbMOs, CHAT reporter hnbMOs pre-labeled with adeno-associated virus (AAV)-hSYN-GFP were co-cultured with GW15 brain slices in the nucleus basalis region (Figures 3L and S2H). After 2 weeks of co-culture, hnbMO-derived CHNs survived well, extended long branched neurites, and projected abundant GFP⁺ fibers into the fetal cortex over distances exceeding 2 cm (Figures 3M–3O).

Together, our results demonstrated the characterization of CHNs in hnbMO that projected to target regions in both mouse brain and human fetal brain slices.

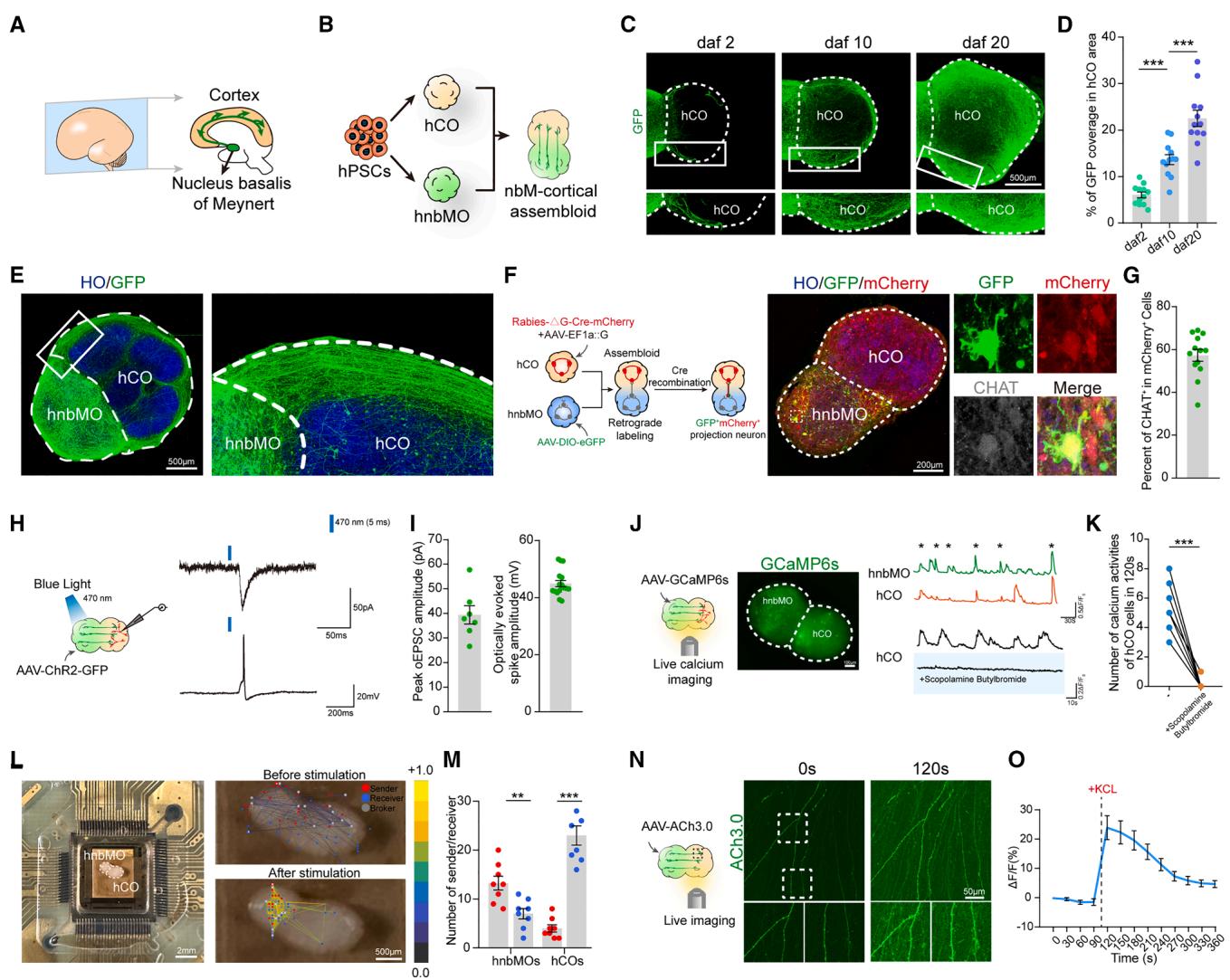

¶ Generation of nbM-cortical assembloids in vitro

The nbM is critical for cognitive function through its cortical projections (Figure 4A).52–54 By fusing hnbMOs with hCOs,we generated nbM-cortical assembloids in vitro (Figure 4B). After fusion, hCOs expanded more rapidly than hnbMOs (Figures S3A and S3B), consistent with the rapid expansion of the cortex during human brain development. To visualize the projections, we labeled the hnbMOs with AAV-hSYN-GFP prior to fusion. At 20 days post-fusion, hCO and hnbMO retained their regional markers (Figures S3C and S3D), with approximately of GFP⁺ cells expressing NKX2.1 and over expressing CHAT (Figures S3E and S3F). Meanwhile, we observed abundant hnbMO-derived projection bundles in the hCO of the assembloid (Figure 4C). Notably, projections into the hCO increased over time to ), while avoiding the VZ of the hCO (Figures 4C–4E), consistent with normal physiology. We next labeled hCOs with mCherry and hnbMOs with GFP. After 20 days of fusion, few mCherry+ hCO-to-hnbMO but abundant hnbMO-to-hCO projections were observed, validating their directional projection (Figures S3G and S3H). Moreover, we used the CHAT reporter cell line to produce nbM-cortical assembloids. Live-cell imaging revealed progressive increases in the tdTomato+ cholinergic projections in the hCO, along with dynamic growth cone motility (Figures S3I– S3K; Video S4).

To verify the synaptic connections between hnbMO-derived CHNs and hCO, we performed rabies virus retrograde labeling (Figure 4F). We respectively infected hCOs with RV-ΔG-CremCherry/AAV-EF1a::G and hnbMOs with AAV-DIO-eGFP for Cre-dependent GFP expression. We observed widespread expression of mCherry in the hCO and the presence of GFP and mCherry double-positive cells in the hnbMO side at 10 days after fusion, with nearly of these cells being CHAT+ CHNs, indicating that CHNs derived from hnbMOs form synaptic connections with hCOs (Figure 4G). Furthermore, immunohistochemical analysis revealed co-localization of the presynaptic marker SYP and the postsynaptic marker PSD95 in the projections from hnbMO to hCO (Figure S4A). In addition, staining for TBR1 and STAB2 identified deep- and upper-layer cortical neurons in the hCO, confirming that neurites had extended into the cortical region (Figure S4B). To assess functional synaptic connectivity in assembloids, hnbMOs were pre-labeled with optogenetic viral vectors and fused with hCOs. At 20 days after fusion, optically evoked excitatory postsynaptic currents (EPSCs) with an average amplitude of approximately 40 pA and neuronal firing were detected in hCO neurons following 470-nm light stimulation on the hnbMO side (Figures 4H, 4I, and S4C), demonstrating synaptic connections between hnbMO and hCO.

To assess emergent network properties in assembloids, we performed calcium imaging and observed synchronized calcium activity between hnbMOs and hCOs (Figure 4J). After treatment with the ACh receptor antagonist scopolamine butylbromide, calcium activity in hCO cells was significantly suppressed (Figure 4K), whereas the addition of the nicotinic receptor antagonist mecamylamine had minimal effect (Figures S4D and S4E). These results indicated that cortical calcium signaling was regulated by cholinergic inputs primarily via muscarinic receptors. By contrast, scopolamine butylbromide had no effect on calcium activity in hCOs alone, supporting that CHNs in hnbMOs modulated calcium signaling in nbM-cortical assembloids (Figures S4F and S4G). We next applied the HD-MEA in nbMcortical assembloids, which detected a greater number of electrophysiological activity senders on the hnbMO side and more receivers on the hCO side under unstimulated conditions (Figures 4L and 4M). To further assess functional connectivity, localized electrical stimulation of the hnbMO region elicited electrical spikes in the hCO side (Figures 4L and S4H), confirming functional connections between hnbMOs and hCOs. Furthermore, optogenetic field potential recordings showed that optical stimulation of AAV-ChR2-GFP–labeled hnbMOs elicited a field potential of in the hCO (Figures S4I and S4J). These results demonstrated that nbM-cortical assembloids formed effective neural projection connections with synchronized network signaling.

To assess ACh release in assembloids, we infected hnbMOs with the sensor. 7 days after fusion, projection fibers extended into the hCO, and upon KCl stimulation, these fibers showed increased fluorescence intensity and synaptic vesicle number, confirming dynamic ACh release into the hCO (Figures 4N and 4O). We also examined the effect of ACh input on the expression of m-type ACh receptors (m-AChR) in the hCO. Confocal microscopy showed a marked increase in the expression of m-AChR in the hCO after fusion (Figures S4K and S4L). These results suggest that hnbMOs containing CHNs release ACh, enhancing the expression of ACh receptors in the hCO.

¶ Construction of nbM-cortical projections in transplanted assembloids

To reconstruct human nbM-cortical pathways in vivo, we innovatively transplanted the corresponding organoids into the cortical and nbM of mice to create transplant assembloids. Both grafted mCherry+ hCOs and hnbMOs showed well survival at 6 months post-transplantation (Figure 5A). Of note, extensive hnbMOs-derived cholinergic projections were observed in hCOs after transplantation (Figures 5B–5D). The overall projection preference of CHNs in dual-transplanted mice closely resembled the projection pattern observed in grafted nbMOs described previously. Meanwhile, grafted hCOs sent out abundant projections to multiple regions of the host brain, which followed in vivo cortical projection patterns (Figures 5E and 5F). Notably, bundles of mCherry+ neurites were observed passing through and segregating the grafted hnbMOs (Figure 5B).

To verify functional synaptic connectivity in vivo, hnbMOs were pre-labeled with optogenetic viral vectors before transplantation. At 4 months post-grafting, 470-nm light stimulation of the hnbMOs graft elicited approximately 20 pA of optogenetically evoked excitatory postsynaptic current (oEPSCs) in mCherry-labeled hCO neurons, indicating functional synapse formation between transplanted hnbMOs and hCOs (Figures 5G and 5H).

Together, these results confirmed that we have established a human nbM-cortical cholinergic projection in the mouse model, with the transplanted hCOs projecting to the deep brain of the host.

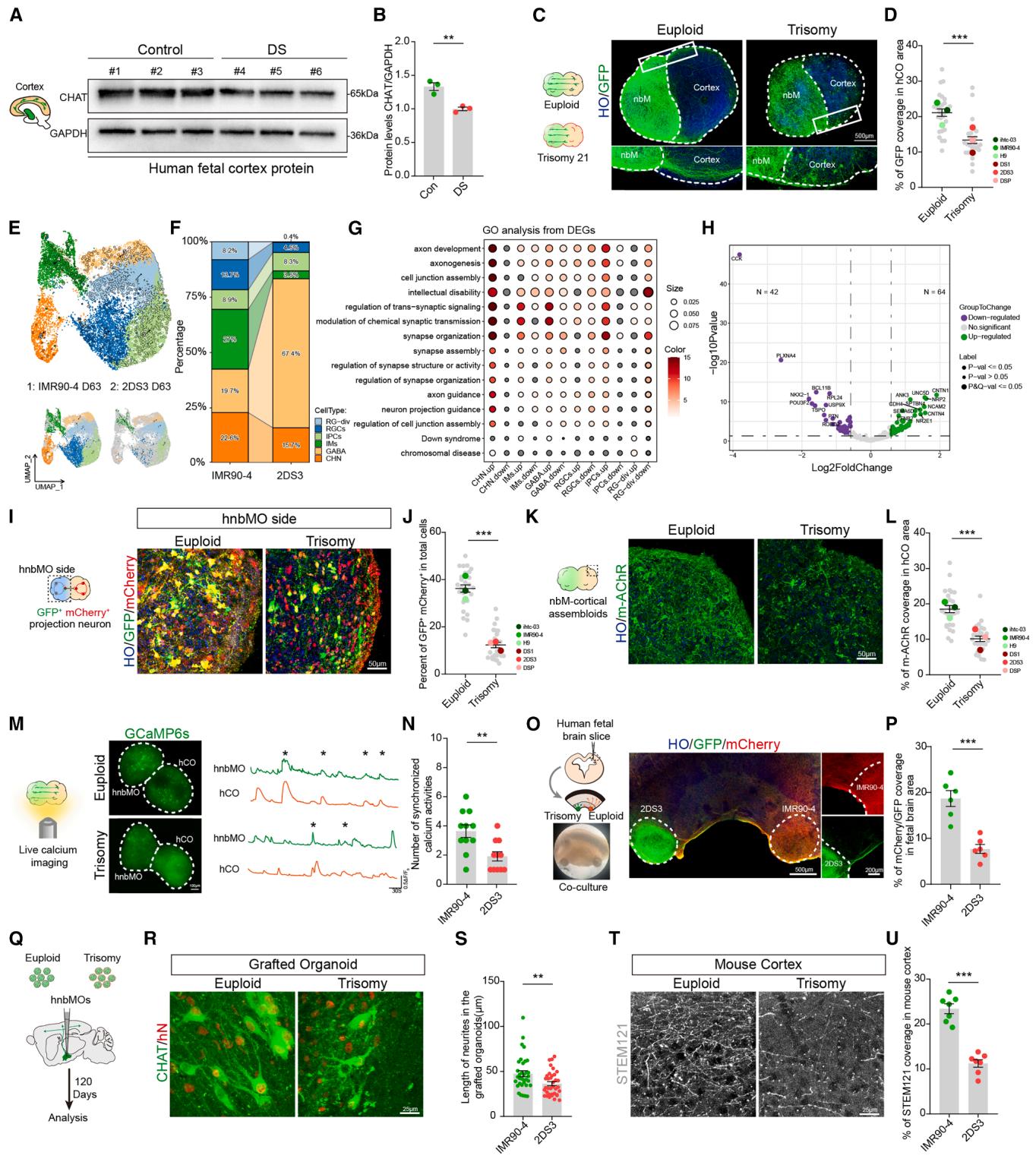

¶ Modeling cholinergic projection deficits of the nbM-cortical pathway in DS

Lastly, we examined whether nbM-cortical assembloids could be used to model cholinergic projection defects associated with neurodevelopmental disorders. DS is a genetic disorder associated with intellectual disability, caused by an extra copy of chromosome 21. Previous studies have shown that DS patients exhibit amyloid precursor protein (APP)-related neuropathologies and reduced ACh activity,55,56 suggesting that aberrant cholinergic connectivity may underlie the cognitive impairments observed in DS. We validated CHAT expression in the cortex of mid-gestation fetal brains and mouse brains. Notably, immunostaining and western blot results showed that the CHAT expression in the cortex of DS was significantly reduced compared with control (Figures 6A, 6B, and S5A–S5D), suggesting a reduction of cholinergic neuronal projection in the DS cortex. However, it is not known whether assembloids derived from DS patients could recapitulate the nbM-cortical pathway defects.

Figure 4. Characterization of nbM-cortical assembloids

(A) Schematic diagram describing nbM-cortical projections in the developing human forebrain at mid-gestation.

(B) In vitro modeling of nbM-cortical projections using assembloids derived from hPSCs.

© Representative images of neurite extension and elongation in nbM-cortical assembloids at days after fusion (daf) 2, 10, and 20 (scale bar, . (D) Scatterplots with the bar showing the percentage of coverage per area on the hCO side at daf 2, 10, and 20. The data were obtained from 3 independent biological experiments. assembloids per group; one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison test; mean SEM; . (E) Representative images of hnbMO-derived hSYN-GFP projections in nbM-cortical assembloids at daf 20 (scale bar, ).

(F) Schematic detailing retrograde viral tracing experiment in nbM-cortical assembloids and representative images of nbM-cortical assembloid at daf 10 showing co-expression of GFP, mCherry, and CHAT on the hnbMO side (scale bar, ).

(G) Scatterplots showing the percent of cells in mCherry+ cells. The data were obtained from 3 independent biological experiments. assembloids; 1–2 random slices were quantified for each organoid; mean SEM.

(H) Schematic of the optogenetic EPSCs and neuronal firing recording of assembloids at daf 20 stimulated by light-emitting diode (LED) light.

Scatterplots showing the quantification of the peak optogenetic EPSC amplitude and optically evoked spike amplitude in assembloids at daf 20. The data were obtained from 3 independent biological experiments. assembloids; mean SEM.

(J) Schematic illustrating spontaneous live calcium imaging of assembloids, nbM-cortical assembloids expressing GCaMP6s, and example traces of cells. Representative ΔF/F₀ traces showing spontaneous calcium in hCO cells blocked by scopolamine butylbromide (scale bar, .

(K) Scatterplots with the bar showing quantification of the number of calcium activities for baseline and for 120 s after exposure to scopolamine butylbromide. The data were obtained from 3 independent biological experiments. cells from 4 assembloids; two-tailed paired test; .

(L) Representative image of nbM-cortical assembloid at daf 20 recording using the HD-MEA Accura Chip (right). Functional connectivity maps of neural activity recorded from the MEA before (top) and after (bottom) electrical stimulation (scale bar, , left; , right).

(M) Scatterplots with the bar showing quantification of the number of sender and receiver nodes detected in nbM-cortical assembloids. The data were obtained from 3 independent biological experiments. assembloids; two-tailed paired t test; mean SEM; , .

(N) Time-lapse of fluorescence under the treatment of KCl ( (scale bar, .

(O) Representative ΔF/F traces showing fluorescence responses in cells before and after adding KCl (40 mM). The data were obtained from 3 independent biological experiments. assembloids; mean SEM.

Figure 5. Establishment of nbM-cortical projections in assembloid transplantation

(A) Schematic of the dual-transplantation experimental design (left), representative images of mCherry and STEM121 in grafted mouse brain at 6 months posttransplantation (right) (scale bar, .

(B) Representative images of VACHT and GFP in grafted hCOs, and mCherry and hN in grafted hnbMOs (scale bar, , top; , bottom). © Scatterplots showing the percentage of coverage per area in grafted hCO at 6 months post-transplantation. The data were obtained from 3 independent biological experiments. mice; mean .

(D) Representative images of GFP, mCherry, and STEM121 in grafted hCOs at 6 months post-transplantation (scale bar, ).

(E) Schematic illustration of projection tracing in the dual-transplantation experiment of hnbMOs and hCOs. Representative images showing GFP⁺ projections derived from grafted hnbMOs (middle) and mCherry⁺ projections from grafted hCOs (right) in multiple brain regions at 6 months post-transplantation. Basolateral amygdala (BLA), caudate putamen (CPu), hippocampus (HPC), thalamus (TH), and cerebral peduncle (CP) (scale bar, ).

(F) Quantification of percentage of GFP and mCherry fluorescence coverage. The data were obtained from 3 independent biological experiments. mice; mean .

(G) Schematic and representative images of whole-cell patch-clamp recordings from dual-transplanted brain slices under bright-field and mCherry fluorescence (scale bar, , and a schematic of optogenetic EPSCs at 4 months post-transplantation.

(H) Scatterplots showing the quantification of oEPSC amplitudes in dual-transplanted brain slices. The data were obtained from 3 independent biological experiments. cells from 6 mice; mean SEM.

Figure 6. Modeling of projection defect in nbM-cortical assembloids derived from patients with DS

(A) Representative western blot of CHAT levels in control and DS human fetal cortex at GW18.

(B) Representative relative quantitation of CHAT levels in control and DS human fetal cortex. The data were obtained from 3 independent biological experiments.

fetal brains per group; two-tailed paired t test; mean SEM; .

© Schematic of euploid and trisomy 21 nbM-cortical assembloids and immunostaining for GFP at daf 20 in euploid and trisomy assembloids (scale bar, ).

(D) Scatterplots with the bar showing the percentage of GFP coverage per area of the hCO side. The data were obtained from 3 independent biological experiments. assembloids from three cell lines per group; two-tailed unpaired t test; mean SEM. .

(E) UMAP plot of cell types detected in euploid and trisomy 21 hnbMOs at day 63.

(F) Percentage of all cell types in the scRNA-seq data splitting by groups.

(G) GO analysis of DEGs between trisomy 21 and euploid organoids splitting by cluster.

(H) Volcano plot of DEGs on axon development between euploid and trisomy 21 hnbMOs.

(I) Representative images showing monosynaptically connected GFP⁺/mCherry⁺ projection neurons in the hnbMO side of euploid and trisomy 21 assembloids at

20 daf (scale bar, 50 μm).

(J) Scatterplots with the bar showing the percentage of GFP+ mCherry+ cells in total cells of the hnbMO side. The data were obtained from 3 independent

biological experiments. n = 27 assembloids from three cell lines per group; two-tailed unpaired t test; mean ± SEM. ***p < 0.001.

(K) Representative images of m-AChR in the hCO side of euploid and trisomy 21 assembloids at daf 20 (scale bar, 50 μm).

(L) Scatterplots with the bar showing the quantification of percentage of m-AChR fluorescence coverage per area of CO. The data were obtained from 3 independent biological experiments. n = 27 assembloids from three cell lines per group; two-tailed unpaired t test; mean ± SEM. ***p < 0.001.

(M) Schematic illustrating spontaneous live calcium imaging of euploid and trisomy 21 assembloids, nbM-cortical assembloids expressing GCaMP6s, and

example ΔF/F0 traces of cells (scale bar, 100 μm).

(N) Quantification of the number of calcium activities for euploid and trisomy 21 assembloids. The data were obtained from 3 independent biological experiments.

n = 11 cells from 6 assembloids per group; two-tailed unpaired t test; mean ± SEM. **p < 0.01.

(O) Schematic of euploid and trisomy 21 hnbMOs cultured with human fetal cortex slice. The euploid hnbMOs expressed with mCherry and the trisomy 21

hnbMOs expressed with GFP are cultured with human fetal brain slices at day 37 (left top). Bright field of hnbMOs cultured with human fetal brain slice (left

bottom). Representative images of GFP and mCherry coimmunostaining in the co-culture system (middle) (scale bar, 500 μm, left; 200 μm, right).

§ Quantification of percentage of mCherry and GFP fluorescence coverage in fetal brain area. The data were obtained from 3 independent biological experiments. n = 6 co-culture slices from 3 fetal brains; two-tailed unpaired t test; mean ± SEM. ***p < 0.001.

(Q) Schematic of the experimental design for transplantation of euploid and trisomy 21 hnbMOs.

® Representative images of CHAT coimmunostaining with hN in euploid and trisomy 21 grafted hnbMOs of transplanted mouse at 120 days post-transplantation

(scale bar, 25 μm).

(S) Quantification of the length of neurites in the euploid and trisomy 21 grafted hnbMOs. The data were obtained from 3 independent biological experiments.

n = 34 cells from 7 mice per group; 5–6 random slices were quantified for each brain. Two-tailed unpaired t test; mean ± SEM. **p < 0.01.

(T) Representative images of STEM121 immunostaining in the cortex of a mouse transplanted with euploid and trisomy 21 hnbMOs at 120 days post-transplantation (scale bar, 25 μm).

(U) Quantification of percentage of STEM121 coverage in the cortex of mouse transplanted with euploid and trisomy 21 hnbMOs. The data were obtained from

3 independent biological experiments. n = 7 mice per group; two-tailed unpaired t test; mean ± SEM. ***p < 0.001.

See also Figure S5.

To investigate whether nbM-cortical projection deficits in DS could be modeled, we differentiated hiPSCs derived from DS patients into hnbMOs. These hnbMOs expressed FOXG1 and NKX2.1 and produced CHAT+ NEUN+ neurons (Figure S5E), indicating their nucleus basalis characteristics. We differentiated three control hPSC lines and three DS iPSC lines 19 and found that the proportion of MGE progenitor cells (NKX2.1) and CHNs (CHAT) was significantly lower in DS hnbMOs (NKX2.1: vs. ; CHAT: vs. (Figures S5F– S5I), aligning with DS pathological phenotypes.3,5 Consistently, western blot analysis further confirmed reduced CHAT protein levels in DS hnbMOs derived from three individuals (Figures S5J and S5K). Next, we generated nbM-cortical assembloids using both DS-derived and control-derived organoids to examine neuron projections. At 20 days after fusion, markedly fewer nerve fibers from the hnbMO were observed in the hCO region of DS-derived assembloids compared with controls (Figures 6C and 6D), indicating impaired projections in DS.

To systematically characterize neuronal projection abnormalities in DS nbM-cortical assembloids, we conducted scRNA-seq on day 63 differentiated hnbMOs derived from DS and control hiPSCs cells) (Figure 6E). Transcriptomic analysis revealed a reduction in CHNs in DS hnbMOs (Figure 6F). Gene Ontology (GO) analysis of differentially expressed genes (DEGs) showed significant enrichment in pathways related to axonogenesis and axon development, with the most pronounced changes in CHN (Figure 6G). The volcano plot visualized DEGs associated with axon development between DS and control hnbMOs (Figure 6H). Among these DEGs associated with axonal development, previous studies have identified ANK3 and NCAM2 as being linked to neurodevelopmental disorders in DS.57,58 The observed overlap between transcriptomic signatures in DS hnbMOs and pathways implicated in projection defects establishes this in vitro platform as a testable framework for probing developmental anomalies.

To verify whether DS-derived assembloid exhibits connectivity deficits, we performed rabies virus retrograde tracing in DSderived assembloids. Following immunostaining, we observed a significant reduction in the proportion of GFP and mCherry double-positive cells in the hnbMO side of DS assembloids (Figures 6I and 6J), indicating a decrease in projection neurons forming synaptic connections with the hCO in DS assembloids. The hCO in DS assembloids displayed reduced ACh receptor expression corresponding to the defective cholinergic projections (Figures 6K and 6L). Live-cell calcium imaging also revealed a substantial reduction in synchronized calcium activity between hnbMO and hCO in DS assembloids compared with controls, indicating impaired neural network events (Figures 6M and 6N). To further detect the defective projection origination, we pre-labeled DS-derived hnbMOs with GFP and control hnbMOs with mCherry and co-cultured both with human fetal cortical slices (Figure 6O). After 2 weeks of co-culture, fibers from DS hnbMOs were significantly fewer than mCherry+ fibers from the control (Figure 6P), demonstrating that the projection deficits primarily originate from neuronal abnormalities in the DS-derived hnbMOs rather than the target hCO.

To further investigate the defects in CHNs, we found that neurite length was reduced both in DS hnbMOs and fetal brains (Figures S5H, S5I, S5L, and S5M). Moreover, live-cell imaging revealed a decreased neurite growth rate, indicating impaired growth and development of DS CHNs (Figures S5N and S5O). MEA analysis showed a decreased number of spikes in DS hnbMOs (Figures S5P and S5Q), indicating functional impairment. These findings suggest that developmental defects in CHNs are a key contributor to their impaired projections toward the hCO. To further validate these findings in vivo, we transplanted control and DS hnbMOs into the mouse brain (Figure 6Q). At 3 months after transplantation, both control and DS hnbMOs demonstrated robust survival in the mouse nbM region (Figure 6R). Immunostaining revealed that the longest neurites of CHAT⁺hN⁺ neurons in the grafted DS hnbMOs were reduced, compared with the control group (Figure 6S). Moreover, fewer human-derived neurites were observed in the cortex of mice transplanted with DS hnbMOs (Figures 6T and 6U), consistent with the projection deficits seen in assembloids.

Together, these findings demonstrate that hnbMOs and nbMcortical assembloids effectively model disease-related projection defects and neural activity abnormalities in DS.

¶ DISCUSSION

The nbM is a crucial nucleus located in the basal forebrain, characterized by its abundance of CHNs, and its dysfunction has a significant impact on neurological and psychiatric disorders.59–63 In this study, we constructed hnbMOs with a high proportion of functional CHNs. Specifically, in contrast to previous MGE organoid protocols that mainly give rise to interneuron populations, we combined enhanced SHH signaling with supplementation of -NGF, which allowed us to generate hnbMOs enriched in CHNs, representing a distinct lineage output compared with conventional MGE models (Table S1).6,16,64,65

Given that many nuclei arise from the MGE, distinguishing nbM identity is essential. Our transcriptomic data show that nbMOs closely match the nbM region in both human and mouse brains, with much lower similarity to other MGE-derived nuclei. Despite its importance, no in vitro models exist for its cholinergic pathway. We therefore generated nbM-cortical assembloids that recapitulate key features, including cholinergic projections and synapse formation with cortical neurons.

One of the key innovations of this study is the dual transplantation. Traditional single-region transplantation cannot fully model human neuron pathways in mice, as the origin or termination of pathways is often heterologous.20,21,49 By utilizing dual transplantation, we have successfully established the first intact human-derived neural pathway in mice with homologous projection initiation and termination regions. This approach may provide a more accurate model for investigating neurological or psychiatric disorders that involve interactions between different brain regions. Future studies could focus on investigating how these grafted organoid connections contribute to host neural activity and behavior.

Current DS research faces significant challenges due to the limitations of existing models, which could not fully replicate human-specific trisomic gene expression.66 Patient-derived organoids and assembloids provide a promising platform for investigating neural pathway dysfunction in DS. Our data indicated that reduced CHNs production may contribute to decreased cholinergic projections, as our hnbMOs effectively recapitulate this key pathological feature observed in DS fetal brain tissues. Moreover, scRNA-seq analysis revealed that disrupted axonal projections in DS hnbMOs may be attributed to dysregulation of axon-related molecules such as ANK3 and NCAM2. Aberrant splicing of ANK3, which is critical for axon initial segment integrity and neuronal polarity,57 has been reported in DS and may underlie impaired axonal development in our DS organoids. Meanwhile, NCAM2, a chromosome 21-encoded neural adhesion molecule involved in neurite outgrowth and polarity,58 is overexpressed in DS organoids, potentially disrupting cytoskeletal organization and might lead to axonal misguidance or retraction. These findings suggest that both diminished neuronal production and impaired projection capability contribute to the observed projection deficits. Future work could elucidate how these molecular alterations contribute to impaired neuronal complexity, axonal development, and network dysfunction in DS.

Besides projection deficits, we observed a significantly increased proportion of GABA in the nbM organoids derived from DS iPSCs, consistent with previous studies.20,67 This shift in neuronal subtype composition may disrupt the excitatory/ inhibitory (E/I) balance. Such an imbalance is likely to impair key functional properties of the neuronal network.68 Indeed, our MEA recordings revealed decreased neuronal excitability and a reduction in spiking activity and a reduction in burst spiking activity in DS nbMOs compared with controls. These data suggest that an altered GABAergic/cholinergic ratio may contribute to network-level deficits in DS. Future studies will focus on dissecting the underlying mechanisms and exploring potential therapeutic interventions to restore the E/I balance.

Notably, Sun et al. reported that CHNs from the basal forebrain could rapidly integrate into glioblastoma and promote tumor growth,69 thereby revealing a previously unrecognized role of BFCNs in tumor biology. However, there remains a lack of a 3D human model that recapitulates BFCNs with stable ACh output. Our work may resolve this challenge by utilizing hnbMOs, which provide ACh output and may serve as a finer model for investigating neuron-cancer interactions in vitro. Overall, our work presents a promising avenue to model the human nucleus basalis and provides pioneering insights into nbM-cortical pathway-related neuron disorders.

¶ Limitations of the study

Despite the significant advancements presented in this study, several limitations remain. The maturation of organoids is still limited compared with their in vivo counterparts, potentially affecting the full recapitulation of CHNs functionality and connectivity. Enhancing organoid culture systems, such as through the incorporation of vascularization, will better mimic physiological environments and promote higher levels of maturation, which are crucial for future studies. Furthermore, while this study focused on the construction and investigation of hnbMOs and their projections, it did not address the signaling inputs to the nbM. Future research should aim to integrate upstream brain region organoids with hnbMOs and hCOs to elucidate the regulatory mechanisms and their potential contributions to disease phenotypes.

¶ RESOURCE AVAILABILITY

¶ Lead contact

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the lead contact, Yan Liu (yanliu@njmu.edu.cn).

¶ Materials availability

This study did not generate new, unique reagents.

¶ Data and code availability

Sequencing data have been deposited in the Gene Expression Omnibus database (GEO: GSE286235) and are publicly available as of publication. The accession numbers for the published datasets analyzed in this paper are listed in the key resources table. This study does not report original algorithms. Any additional information required to reanalyze the data reported in this paper is available from the lead contact upon request.

¶ ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China grants (82325015, 82530038, 82171528, 82371260, U23A20429, 22274079, and 5203302); the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2021YFA1101803, 2021YFA1101802, 2025YFC3408902, 2022YFA1104800, and 2023YFF1203600); the Joint Project of the Yangtze River Delta Science and Technology Innovation Community (2024CSJZN0600); the Natural Science Foundation of Jiangsu Province (BK20240131 and BK20240520); the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (2024M761478); the Scientific Innovation Research of College Graduate in Jiangsu Province (KYCX24_2008); and the Basic Research Program of Jiangsu, Jiangsu Province Innovation center for Brain-Inspired intelligence technology (BM2024001).

¶ AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

D.W., X.Z., X.G., and Y.L. designed the experiment. D.W., X.Z., X.-Y.T., and Y.L. wrote the manuscript. D.W. and X.Z. performed the experiments with technical assistance from X.-Y.T., S.W., M.T., C.C., H.H., Y.Z., W.Z., X.H., M.X., Y.D., and X.G. X.Q. and Q.C. collected human tissue samples. H.Y. and Y.H. performed scRNA-seq analysis. Y.G. and X.Z. performed optogenetic patch-clamp experiments. D.W. and X.Z. performed additional data analyses. Y.L. directed the project.

¶ DECLARATION OF INTERESTS

The authors declare no competing interests.

¶ STAR★METHODS

Detailed methods are provided in the online version of this paper and include the following:

¶ • KEY RESOURCES TABLE

• EXPERIMENTAL MODEL AND STUDY PARTICIPANT DETAILS

○ Cell lines

Human primary brain tissue

Animals

¶ METHOD DETAILS

Generation of hnbMOs

Generation of hCOs

○ Generation of CHAT-tdTomato hiPSC line using CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing

Generation of nbM-cortical assembloids

○ Co-Culture of human fetal brain tissue and organoids

○ Dissociation of organoids for 2D culture

Frozen section and immunocytochemistry

Tissue clearing and 3D reconstruction of brain organoids

Viral labeling

Live-cell imaging

Retrograde rabies tracing in nbM-cortical assembloids

Single-cell RNA sequencing and analysis

Western blot

Whole-cell patch-clamp recordings

Optogenetic stimulation

MEA assay

Electrical stimulation and recording of nbM-cortical assembloids

Organoids transplantation

MRI of transplanted mice

¶ QUANTIFICATION AND STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

Statistical analysis

Quantification of fluorescence intensity

Quantification of projection

○ Quantification of neurite outgrowth from grafted hnbMOs

¶ SUPPLEMENTAL INFORMATION

Supplemental information can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.

stem.2025.10.004.

Received: March 3, 2025

Revised: August 22, 2025

Accepted: October 5, 2025

¶ REFERENCES

- Woolf, N.J. (1991). Cholinergic systems in mammalian brain and spinal cord. Prog. Neurobiol. 37, 475–524. https://doi.org/10.1016/0301-0082 (91)90006-m.

- Ballinger, E.C., Ananth, M., Talmage, D.A., and Role, L.W. (2016). Basal Forebrain Cholinergic Circuits and Signaling in Cognition and Cognitive Decline. Neuron 91, 1199–1218. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuron.2016. 09.006.

- Yates, C.M., Simpson, J., Maloney, A.F., Gordon, A., and Reid, A.H. (1980). Alzheimer-like cholinergic deficiency in Down syndrome. Lancet 2, 979. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(80)92137-6.

- Baker-Nigh, A., Vahedi, S., Davis, E.G., Weintraub, S., Bigio, E.H., Klein, W.L., and Geula, C. (2015). Neuronal amyloid- accumulation within cholinergic basal forebrain in ageing and Alzheimer’s disease. Brain 138, 1722–1737. https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/awv024.

- Casanova, M.F., Walker, L.C., Whitehouse, P.J., and Price, D.L. (1985). Abnormalities of the nucleus basalis in Down’s syndrome. Ann. Neurol. 18, 310–313. https://doi.org/10.1002/ana.410180306.

- Liu, Y., Weick, J.P., Liu, H., Krencik, R., Zhang, X., Ma, L., Zhou, G.M., Ayala, M., and Zhang, S.C. (2013). Medial ganglionic eminence-like cells derived from human embryonic stem cells correct learning and memory deficits. Nat. Biotechnol. 31, 440–447. https://doi.org/10. 1038/nbt.2565.

- Hu, Y., Qu, Z.Y., Cao, S.Y., Li, Q., Ma, L., Krencik, R., Xu, M., and Liu, Y. (2016). Directed differentiation of basal forebrain cholinergic neurons from human pluripotent stem cells. J. Neurosci. Methods 266, 42–49. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jneumeth.2016.03.017.

- Yue, W., Li, Y., Zhang, T., Jiang, M., Qian, Y., Zhang, M., Sheng, N., Feng, S., Tang, K., Yu, X., et al. (2015). ESC-Derived Basal Forebrain Cholinergic Neurons Ameliorate the Cognitive Symptoms Associated with Alzheimer’s Disease in Mouse Models. Stem Cell Rep. 5, 776–790. https://doi.org/10. 1016/j.stemcr.2015.09.010.

- Amin, N.D., and Pas‚ca, S.P. (2018). Building Models of Brain Disorders with Three-Dimensional Organoids. Neuron 100, 389–405. https://doi. org/10.1016/j.neuron.2018.10.007.

- Lancaster, M.A., Renner, M., Martin, C.A., Wenzel, D., Bicknell, L.S., Hurles, M.E., Homfray, T., Penninger, J.M., Jackson, A.P., and Knoblich, J.A. (2013). Cerebral organoids model human brain development and microcephaly. Nature 501, 373–379. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature12517.

- Pas‚ ca, A.M., Sloan, S.A., Clarke, L.E., Tian, Y., Makinson, C.D., Huber, N., Kim, C.H., Park, J.Y., O’Rourke, N.A., Nguyen, K.D., et al. (2015). Functional cortical neurons and astrocytes from human pluripotent stem cells in 3D culture. Nat. Methods 12, 671–678. https://doi.org/10.1038/ nmeth.3415.

- Qian, X., Nguyen, H.N., Song, M.M., Hadiono, C., Ogden, S.C., Hammack, C., Yao, B., Hamersky, G.R., Jacob, F., Zhong, C., et al. (2016). BrainRegion-Specific Organoids Using Mini-bioreactors for Modeling ZIKV Exposure. Cell 165, 1238–1254. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2016.04.032.

- Kadoshima, T., Sakaguchi, H., Nakano, T., Soen, M., Ando, S., Eiraku, M., and Sasai, Y. (2013). Self-organization of axial polarity, inside-out layer pattern, and species-specific progenitor dynamics in human ES cellderived neocortex. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 110, 20284–20289. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1315710110.

- Xiang, Y., Tanaka, Y., Cakir, B., Patterson, B., Kim, K.Y., Sun, P., Kang, Y.J., Zhong, M., Liu, X., Patra, P., et al. (2019). hESC-Derived Thalamic Organoids Form Reciprocal Projections When Fused with Cortical Organoids. Cell Stem Cell 24, 487–497. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.stem. 2018.12.015.

- Muguruma, K., Nishiyama, A., Kawakami, H., Hashimoto, K., and Sasai, Y. (2015). Self-organization of polarized cerebellar tissue in 3D culture of human pluripotent stem cells. Cell Rep. 10, 537–550. https://doi.org/10. 1016/j.celrep.2014.12.051.

- Xiang, Y., Tanaka, Y., Patterson, B., Kang, Y.J., Govindaiah, G., Roselaar, N., Cakir, B., Kim, K.Y., Lombroso, A.P., Hwang, S.M., et al. (2017). Fusion of Regionally Specified hPSC-Derived Organoids Models Human Brain Development and Interneuron Migration. Cell Stem Cell 21, 383–398. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.stem.2017.07.007.

- Miura, Y., Li, M.Y., Birey, F., Ikeda, K., Revah, O., Thete, M.V., Park, J.Y., Puno, A., Lee, S.H., Porteus, M.H., and Pașca, S.P. (2020). Generation of human striatal organoids and cortico-striatal assembloids from human pluripotent stem cells. Nat. Biotechnol. 38, 1421–1430. https://doi.org/ 10.1038/s41587-020-00763-w.

- Andersen, J., Revah, O., Miura, Y., Thom, N., Amin, N.D., Kelley, K.W., Singh, M., Chen, X., Thete, M.V., Walczak, E.M., et al. (2020). Generation of Functional Human 3D Cortico-Motor Assembloids. Cell 183, 1913–1929. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2020.11.017.

- Tang, X.Y., Xu, L., Wang, J., Hong, Y., Wang, Y., Zhu, Q., Wang, D., Zhang, X.Y., Liu, C.Y., Fang, K.H., et al. (2021). DSCAM/PAK1 pathway suppression reverses neurogenesis deficits in iPSC-derived cerebral organoids from patients with Down syndrome. J. Clin. Invest. 131, e135763. https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI135763.

- Xu, R., Brawner, A.T., Li, S., Liu, J.J., Kim, H., Xue, H., Pang, Z.P., Kim, W.Y., Hart, R.P., Liu, Y., and Jiang, P. (2019). OLIG2 Drives Abnormal Neurodevelopmental Phenotypes in Human iPSC-Based Organoid and Chimeric Mouse Models of Down Syndrome. Cell Stem Cell 24, 908–926. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.stem.2019.04.014.

- Revah, O., Gore, F., Kelley, K.W., Andersen, J., Sakai, N., Chen, X., Li, M. Y., Birey, F., Yang, X., Saw, N.L., et al. (2022). Maturation and circuit integration of transplanted human cortical organoids. Nature 610, 319–326. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-022-05277-w.

- Huang, W.K., Wong, S.Z.H., Pather, S.R., Nguyen, P.T.T., Zhang, F., Zhang, D.Y., Zhang, Z., Lu, L., Fang, W., Chen, L., et al. (2021). Generation of hypothalamic arcuate organoids from human induced pluripotent stem cells. Cell Stem Cell 28, 1657–1670. https://doi.org/10. 1016/j.stem.2021.04.006.

- Kiral, F.R., Cakir, B., Tanaka, Y., Kim, J., Yang, W.S., Wehbe, F., Kang, Y.J., Zhong, M., Sancer, G., Lee, S.H., et al. (2023). Generation of ventralized human thalamic organoids with thalamic reticular nucleus. Cell Stem Cell 30, 677–688. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.stem.2023.03.007.

- Pang, W., Zhu, J., Yang, K., Zhu, X., Zhou, W., Jiang, L., Zhuang, X., Liu, Y., Wei, J., Lu, X., et al. (2024). Generation of human region-specific brain organoids with medullary spinal trigeminal nuclei. Cell Stem Cell 31, 1501– 1512. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.stem.2024.08.004.

- Sussel, L., Marin, O., Kimura, S., and Rubenstein, J.L. (1999). Loss of Nkx2.1 homeobox gene function results in a ventral to dorsal molecular respecification within the basal telencephalon: evidence for a transformation of the pallidum into the striatum. Development 126, 3359–3370. https:// doi.org/10.1242/dev.126.15.3359.

- Allaway, K.C., Mun˜ oz, W., Tremblay, R., Sherer, M., Herron, J., Rudy, B., Machold, R., and Fishell, G. (2020). Cellular birthdate predicts laminar and regional cholinergic projection topography in the forebrain. eLife 9, e63249. https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.63249.

- Reilly, J.O., Karavanova, I.D., Williams, K.P., Mahanthappa, N.K., and Allendoerfer, K.L. (2002). Cooperative effects of Sonic Hedgehog and NGF on basal forebrain cholinergic neurons. Mol. Cell. Neurosci. 19, 88–96. https://doi.org/10.1006/mcne.2001.1063.

- Rubenstein, J.L., Shimamura, K., Martinez, S., and Puelles, L. (1998). Regionalization of the prosencephalic neural plate. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 21, 445–477. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.neuro.21.1.445.

- Wilson, S.W., and Rubenstein, J.L. (2000). Induction and dorsoventral patterning of the telencephalon. Neuron 28, 641–651. https://doi.org/10. 1016/s0896-6273(00)00171-9.

- Magno, L., Kretz, O., Bert, B., Erso¨ zlu¨ , S., Vogt, J., Fink, H., Kimura, S., Vogt, A., Monyer, H., Nitsch, R., and Naumann, T. (2011). The integrity of cholinergic basal forebrain neurons depends on expression of Nkx2- 1. Eur. J. Neurosci. 34, 1767–1782. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-9568. 2011.07890.x.

- Scuderi, S., Kang, T.Y., Jourdon, A., Nelson, A., Yang, L., Wu, F., Anderson, G.M., Mariani, J., Tomasini, L., Sarangi, V., et al. (2025). Specification of human brain regions with orthogonal gradients of WNT and SHH in organoids reveals patterning variations across cell lines. Cell Stem Cell 32, 970–989. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.stem.2025.04.006.

- Fleck, J.S., Sanchı´s-Calleja, F., He, Z., Santel, M., Boyle, M.J., Camp, J.G., and Treutlein, B. (2021). Resolving organoid brain region identities by mapping single-cell genomic data to reference atlases. Cell Stem Cell 28, 1148–1159. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.stem.2021.02.015.

- Hawrylycz, M.J., Lein, E.S., Guillozet-Bongaarts, A.L., Shen, E.H., Ng, L., Miller, J.A., van de Lagemaat, L.N., Smith, K.A., Ebbert, A., Riley, Z.L., et al. (2012). An anatomically comprehensive atlas of the adult human brain transcriptome. Nature 489, 391–399. https://doi.org/10.1038/ nature11405.

- Li, Y., Li, Z., Wang, C., Yang, M., He, Z., Wang, F., Zhang, Y., Li, R., Gong, Y., Wang, B., et al. (2023). Spatiotemporal transcriptome atlas reveals the regional specification of the developing human brain. Cell 186, 5892–5909. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2023.11.016.

- Yao, Z., van Velthoven, C.T.J., Kunst, M., Zhang, M., McMillen, D., Lee, C., Jung, W., Goldy, J., Abdelhak, A., Aitken, M., et al. (2023). A high-resolution transcriptomic and spatial atlas of cell types in the whole mouse brain. Nature 624, 317–332. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-023-06812-z.

- Elshatory, Y., and Gan, L. (2008). The LIM-homeobox gene Islet-1 is required for the development of restricted forebrain cholinergic neurons. J. Neurosci. 28, 3291–3297. https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5730- 07.2008.

- Furusho, M., Ono, K., Takebayashi, H., Masahira, N., Kagawa, T., Ikeda, K., and Ikenaka, K. (2006). Involvement of the Olig2 transcription factor in cholinergic neuron development of the basal forebrain. Dev. Biol. 293, 348–357. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.01.031.

- Cho, H.H., Cargnin, F., Kim, Y., Lee, B., Kwon, R.J., Nam, H., Shen, R., Barnes, A.P., Lee, J.W., Lee, S., and Lee, S.K. (2014). Isl1 directly controls a cholinergic neuronal identity in the developing forebrain and spinal cord by forming cell type-specific complexes. PLoS Genet. 10, e1004280. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1004280.

- Sander, M., Paydar, S., Ericson, J., Briscoe, J., Berber, E., German, M., Jessell, T.M., and Rubenstein, J.L. (2000). Ventral neural patterning by Nkx homeobox genes: Nkx6.1 controls somatic motor neuron and ventral interneuron fates. Genes Dev. 14, 2134–2139. https://doi.org/10.1101/ gad.820400.

- Guthrie, S. (2007). Patterning and axon guidance of cranial motor neurons. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 8, 859–871. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrn2254.

- Chen, L., Chatterjee, M., and Li, J.Y.H. (2010). The mouse homeobox gene Gbx2 is required for the development of cholinergic interneurons in the striatum. J. Neurosci. 30, 14824–14834. https://doi.org/10.1523/ JNEUROSCI.3742-10.2010.

- Magno, L., Asgarian, Z., Apanaviciute, M., Milner, Y., Bengoa-Vergniory, N., Rubin, A.N., and Kessaris, N. (2022). Fate mapping reveals mixed embryonic origin and unique developmental codes of mouse forebrain septal neurons. Commun. Biol. 5, 1137. https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-022- 04066-5. 43. Magno, L., Barry, C., Schmidt-Hieber, C., Theodotou, P., Ha¨ usser, M., and Kessaris, N. (2017). NKX2-1 Is Required in the Embryonic Septum for Cholinergic System Development, Learning, and Memory. Cell Rep. 20, 1572–1584. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.celrep.2017.07.053.

- Arber, S., Han, B., Mendelsohn, M., Smith, M., Jessell, T.M., and Sockanathan, S. (1999). Requirement for the homeobox gene Hb9 in the consolidation of motor neuron identity. Neuron 23, 659–674. https://doi. org/10.1016/s0896-6273(01)80026-x.

- Pattyn, A., Hirsch, M., Goridis, C., and Brunet, J.F. (2000). Control of hindbrain motor neuron differentiation by the homeobox gene Phox2b. Development 127, 1349–1358. https://doi.org/10.1242/dev.127.7.1349.

- Zaborszky, L., Csordas, A., Mosca, K., Kim, J., Gielow, M.R., Vadasz, C., and Nadasdy, Z. (2015). Neurons in the basal forebrain project to the cortex in a complex topographic organization that reflects corticocortical connectivity patterns: an experimental study based on retrograde tracing and 3D reconstruction. Cereb. Cortex 25, 118–137. https://doi.org/10. 1093/cercor/bht210.

- Jing, M., Li, Y., Zeng, J., Huang, P., Skirzewski, M., Kljakic, O., Peng, W., Qian, T., Tan, K., Zou, J., et al. (2020). An optimized acetylcholine sensor for monitoring in vivo cholinergic activity. Nat. Methods 17, 1139–1146. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41592-020-0953-2.

- Wu, H., Williams, J., and Nathans, J. (2014). Complete morphologies of basal forebrain cholinergic neurons in the mouse. eLife 3, e02444. https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.02444.

- Schafer, S.T., Mansour, A.A., Schlachetzki, J.C.M., Pena, M., Ghassemzadeh, S., Mitchell, L., Mar, A., Quang, D., Stumpf, S., Ortiz, I.S., et al. (2023). An in vivo neuroimmune organoid model to study human microglia phenotypes. Cell 186, 2111–2126. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell. 2023.04.022.

- Chen, Z.Y., Yang, Y.L., Li, M., Gao, L., Qu, W.M., Huang, Z.L., and Yuan, X.S. (2023). Whole-brain neural connectivity to cholinergic neurons in the nucleus basalis of Meynert. J. Neurochem. 166, 233–247. https://doi.org/ 10.1111/jnc.15873.

- Paredes, M.F., Mora, C., Flores-Ramirez, Q., Cebrian-Silla, A., Del Dosso, A., Larimer, P., Chen, J., Kang, G., Gonzalez Granero, S., Garcia, E., et al. (2022). Nests of dividing neuroblasts sustain interneuron production for the developing human brain. Science 375, eabk2346. https://doi.org/10. 1126/science.abk2346.

- Williams, S.R., and Fletcher, L.N. (2019). A Dendritic Substrate for the Cholinergic Control of Neocortical Output Neurons. Neuron 101, 486–499. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuron.2018.11.035.

- Mei, F., Zhao, C., Li, S., Xue, Z., Zhao, Y., Xu, Y., Ye, R., You, H., Yu, P., Han, X., et al. (2024). Ngfr+ cholinergic projection from SI/nBM to mPFC selectively regulates temporal order recognition memory. Nat. Commun. 15, 7342. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-51707-w.

- Gulledge, A.T., Bucci, D.J., Zhang, S.S., Matsui, M., and Yeh, H.H. (2009). M1 receptors mediate cholinergic modulation of excitability in neocortical pyramidal neurons. J. Neurosci. 29, 9888–9902. https://doi.org/10.1523/ JNEUROSCI.1366-09.2009.

- Weijerman, M.E., van Furth, A.M., Vonk Noordegraaf, A., van Wouwe, J.P., Broers, C.J.M., and Gemke, R.J.B.J. (2008). Prevalence, neonatal characteristics, and first-year mortality of Down syndrome: a national study. J. Pediatr. 152, 15–19. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2007. 09.045.

- Canfield, M.A., Honein, M.A., Yuskiv, N., Xing, J., Mai, C.T., Collins, J.S., Devine, O., Petrini, J., Ramadhani, T.A., Hobbs, C.A., and Kirby, R.S. (2006). National estimates and race/ethnic-specific variation of selected birth defects in the United States, 1999–2001. Birth Defects Res. A Clin. Mol. Teratol. 76, 747–756. https://doi.org/10.1002/bdra.20294.

- Rastogi, M., Bartolucci, M., Nanni, M., Aloisio, M., Vozzi, D., Petretto, A., Contestabile, A., and Cancedda, L. (2024). Integrative multi-omic analysis reveals conserved cell-projection deficits in human Down syndrome brains. Neuron 112, 2503–2523. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuron.2024. 05.002.

- Parcerisas, A., Pujadas, L., Ortega-Gasco´ , A., Perello´ -Amoro´ s, B., Viais, R., Hino, K., Figueiro-Silva, J., La Torre, A., Trulla´ s, R., Simo´ , S., et al. (2020). NCAM2 Regulates Dendritic and Axonal Differentiation through the Cytoskeletal Proteins MAP2 and 14-3-3. Cereb. Cortex 30, 3781– 3799. https://doi.org/10.1093/cercor/bhz342.

- Shafiee, N., Fonov, V., Dadar, M., Spreng, R.N., and Collins, D.L. (2024). Degeneration in Nucleus basalis of Meynert signals earliest stage of Alzheimer’s disease progression. Neurobiol. Aging 139, 54–63. https:// doi.org/10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2024.03.003.

- Hall, H., Reyes, S., Landeck, N., Bye, C., Leanza, G., Double, K., Thompson, L., Halliday, G., and Kirik, D. (2014). Hippocampal Lewy pathology and cholinergic dysfunction are associated with dementia in Parkinson’s disease. Brain 137, 2493–2508. https://doi.org/10.1093/ brain/awu193.

- Perry, E.K., Lee, M.L., Martin-Ruiz, C.M., Court, J.A., Volsen, S.G., Merrit, J., Folly, E., Iversen, P.E., Bauman, M.L., Perry, R.H., and Wenk, G.L. (2001). Cholinergic activity in autism: abnormalities in the cerebral cortex and basal forebrain. Am. J. Psychiatry 158, 1058–1066. https://doi.org/ 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.7.1058.

- Cheng, L., Xu, C., Wang, L., An, D., Jiang, L., Zheng, Y., Xu, Y., Wang, Y., Wang, Y., Zhang, K., et al. (2021). Histamine H1 receptor deletion in cholinergic neurons induces sensorimotor gating ability deficit and social impairments in mice. Nat. Commun. 12, 1142. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467- 021-21476-x.

- Wenk, G.L. (1997). Rett syndrome: neurobiological changes underlying specific symptoms. Prog. Neurobiol. 51, 383–391. https://doi.org/10. 1016/s0301-0082(96)00059-7.

- Birey, F., Andersen, J., Makinson, C.D., Islam, S., Wei, W., Huber, N., Fan, H.C., Metzler, K.R.C., Panagiotakos, G., Thom, N., et al. (2017). Assembly of functionally integrated human forebrain spheroids. Nature 545, 54–59. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature22330.

- Nicholas, C.R., Chen, J., Tang, Y., Southwell, D.G., Chalmers, N., Vogt, D., Arnold, C.M., Chen, Y.J.J., Stanley, E.G., Elefanty, A.G., et al. (2013). Functional maturation of hPSC-derived forebrain interneurons requires an extended timeline and mimics human neural development. Cell Stem Cell 12, 573–586. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.stem.2013.04.005.

- Zhao, X., and Bhattacharyya, A. (2018). Human Models Are Needed for Studying Human Neurodevelopmental Disorders. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 103, 829–857. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajhg.2018.10.009.

- Chakrabarti, L., Best, T.K., Cramer, N.P., Carney, R.S.E., Isaac, J.T.R., Galdzicki, Z., and Haydar, T.F. (2010). Olig1 and Olig2 triplication causes developmental brain defects in Down syndrome. Nat. Neurosci. 13, 927–934. https://doi.org/10.1038/nn.2600.

- Kleschevnikov, A.M., Belichenko, P.V., Gall, J., George, L., Nosheny, R., Maloney, M.T., Salehi, A., and Mobley, W.C. (2012). Increased efficiency of the GABAA and GABAB receptor-mediated neurotransmission in the Ts65Dn mouse model of Down syndrome. Neurobiol. Dis. 45, 683–691. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nbd.2011.10.009.

- Sun, Y., Wang, X., Zhang, D.Y., Zhang, Z., Bhattarai, J.P., Wang, Y., Park, K.H., Dong, W., Hung, Y.F., Yang, Q., et al. (2025). Brain-wide neuronal circuit connectome of human glioblastoma. Nature 641, 222–231. https:// doi.org/10.1038/s41586-025-08634-7.

- Hao, Y., Hao, S., Andersen-Nissen, E., Mauck, W.M., 3rd, Zheng, S., Butler, A., Lee, M.J., Wilk, A.J., Darby, C., Zager, M., et al. (2021). Integrated analysis of multimodal single-cell data. Cell 184, 3573–3587. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2021.04.048.

KEY RESOURCES TABLE

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

| Antibodies | ||

| CHAT | Mililpore | Cat# AB144P; RRID:AB_2079751 |

| CHAT | ABclonal | Cat# A19031; RRID:AB_2862523 |

| TUJ1 | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat# T8660; RRID:AB_477590 |

| TUJ1 | Covance | Cat# PRB-435P; RRID:AB_291637 |

| NKX2.1 | Santa Cru | Cat# sc-13040; RRID:AB_793532 |

| FOXG1 | Abcam | Cat# AB18259; RRID:AB_732415 |

| NEUN | Arigo | Cat# ARG52283; N/A (RRID not available) |

| SOX2 | R&D | Cat# AF2018; RRID:AB_355110 |

| VACHT | Synaptic system | Cat#139103; RRID:AB_887864 |

| mCherry | Abcam | Cat#AB167453; RRID:AB_2571870 |

| mCherry | Abcam | Cat#AB125096; RRID:AB_11133266 |

| GFP | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat# AB3080; RRID: AB_91337 |

| Human Nuclei | Chemicon | Cat# MAB1281; RRID:AB_94090 |

| STEM121 | Takara | Cat# Y40410; RRID:AB_2801314 |

| hSYN | Calbiochem | Cat# 574777; RRID:AB_2200124 |

| GBX2 | Thermo Fisher | Cat# PA5-77984; RRID:AB_2735826 |

| NESTIN | Santa Cruz | Cat# sc-21247; RRID:AB_650014 |

| OLIG2 | Santa Cruz | Cat# sc-19969; RRID:AB_2236477 |

| GABA | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat# A2052; RRID:AB_477652 |

| Calretinin | Swant | Cat# CR7697; RRID:AB_2619710 |

| mAChR | Synaptic system | Cat# 223 017; RRID:AB_2238208 |

| TBR1 | Abcam | Cat# AB31940; RRID:AB_2200219 |

| PKC-入 | BD | Cat# 610207; RRID:AB_397606 |

| PAX6 | Biolegend | Cat# 862001; RRID:AB_2801237 |

| Synaptophysin | Abcam | Cat# AB16659; RRID:AB_443419 |

| PSD95 | Cell Signal Technology | Cat# 2507; RRID:AB_561221 |

| Hoechst33258 | Thermo Fisher | Cat# H3569; RRID:AB_2651133 |

| GAPDH | Peprotech | Cat# 60004-1-Ig; RRID:AB_2107436 |

| Bacterial and virus strains | ||

| RV-CVS-ENVA-N2C(△G)-mCherry-2A-Cre | BrainVTA | R05003 |

| rAAV-EF1a-DIO-EGFP-WPRE-hGH pA | BrainVTA | PT-0795 |

| rAAV-EF1a-RVG-WPRE-poly A | BrainVTA | PT-4870 |

| rAAVCAG-GCaMp6s-WPRE-hGH polyA | BrainVTA | https://www.brainvta.ltd/ |

| rAAV-CAG-ACh3.0-WPREs | BrainVTA | https://www.brainvta.litd/ |

| pAAV-hSYN-EGFP-3xFLAG-WPRE | OBiO | https://www.obiosh.com/ |

| pAAV-hSYN-hChR2 (H134R) -EYFP | OBiO | https://www.obiosh.com/ |

| PAAV-hSYN-MCS-mCherry-3FLAG | OBiO | https://www.obiosh.com/ |

| Chemicals,peptides,and recombinantproteins | ||

| Essential 8 | Life technology | Cat# A14666SA |

| DMEM/F-12 | Thermo Fisher | Cat# C11330500BT |

| N2 Supplement | Thermo Fisher | Cat# 17502-048 |

| NEAA | Gibco | Cat# 11140035 |

| SB431542 | R&D | Cat# 1614/10 |

| DMH1 | R&D | Cat# 4126/10 |

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

| B27 Supplement | Thermo Fisher | Cat# 12587010 |

| Dispase | Gibco | Cat# 17105041 |

| Gentle Cell Disociation Reagent | Stemcell | Cat# 100-0485 |

| Matrigel | Corming | Cat# 354230 |

| P/S antibiotic | Gibco | Cat# 15140122 |

| ROC inhibitor | Stem Cell | Cat# 72304 |

| Vitronectin | Life technology | Cat# A31804 |

| FBS | Life technology | Cat# 10099141 |

| TrypLE | Thermo Fisher | Cat# 12604013 |

| DPBS | Gibco | Cat# 14190136 |

| β-NGF | Peprotech | Cat# 450-1-250 |

| Purmorphamine | Stemgent | Cat# 04-0009 |

| SHH-C24 | R&D system | Cat# 1845-SH |

| SHH-C25 | R&D system | Cat# 464-SH |

| BDNF | Peprotech | Cat# 450-02-100 |

| CAMP | Sigma | Cat# D0260 |

| BrainPhys Neuronal Medium | Stem Cell | Cat# 05790 |

| Penilli/Streptomycin | Life technology | Cat# 15140-122 |

| PFA | Sigma | Cat# 158127 |

| O.C.T compound | SAKURA | Cat# 4583 |

| PBS tablets | Medicago | Cat# 09-9400-100 |

| Donkey serum | Millipore | Cat# S30-KC |

| Triton X-100 | Amresco | Cat# 0694 |

| Scopolamine Butylbromide | AbMole | Cat# M3590 |

| Mecamylamine hydrochloride | AbMole | Cat# M7940 |

| TBST 10X | Sangon | Cat# C006161 |

| RIPA | Thermo Fisher | Cat# 89901 |

| Cocktail | Beyotime | Cat# P1005 |

| NON-Fat Powdered Milk | Sangon | Cat# A600669 |

| CaCI2 | sigma | Cat# 21097-250g |

| KCI | SCR | Cat# 10016318 |

| Nacl | Sigma | Cat# 7647-14-5 |

| HEPES | Sigma | Cat# H3375 |

| NaHCO3 | SCR | Cat# 10018960 |

| MgS04 | SCR | Cat# 10013018 |

| EGTA | Sigma | Cat# 67-42-5 |

| Critical commercial assays | ||

| SCALEVIEW0-S4 | FUJIFILM | Cat# 194-18561 |

| Deposited data | ||