¶ Transplanted human striatal progenitors exhibit functional integration and modulate host circuitry in a Huntington’s disease animal model

Linda Scaramuzza a,b,1 , Marta Ribodino c,d,1 , Christian Cassarino a,b,2 , Marta Morrocchi a,b,2 , Gabriela B Gomez Gonzalez c,d,2 , Roberta Parolisi c,d,2 , Edoardo Sozzi e , Giacomo Turrini c,d , Valentina Cerrato c,d , Paola Conforti a,b , Eriola Hoxha c,d , Riccardo Tognato f , Greta Galeotti a,b , Chiara Cordiglieri b , Maria Cristina Crosti b , Stefano Zucca d,g , Martina Lorenzati c ,d , Serena Bovetti d,g , Paolo Spaiardi h , Claudio de’Sperati i , Gerardo Biella h , Linda Ottoboni j , Malin Parmar e , Simone Maestri a,b , Dario Besusso a,b,* , Elena Cattaneo a,b,*,3 , Annalisa Buffo c,d,**,3

a Department of Biosciences, University of Milan, Milan 20133, Italy

b National Institute of Molecular Genetics “Romeo ed Enrica Invernizzi”, Milan 20122, Italy

c Department of Neuroscience Rita Levi-Montalcini, University of Turin, Turin 10126, Italy

d Neuroscience Institute Cavalieri Ottolenghi, University of Turin, Orbassano 10043, Italy

e Wallenberg Neuroscience Center and Lund Stem Cell Center, Lund University, Lund 22184, Sweden

f Carl Zeiss Spa, Research Microscopy Solution, Milan, Italy

g Department of Life Sciences and Systems Biology, University of Turin, Turin 10123, Italy

h Department of Biology and Biotechnologies, University of Pavia, Pavia 27100, Italy

i Laboratory of Action, Perception and Cognition, Vita-Salute San Raffaele University, Milan 20132, Italy

j Department of Pathophysiology and Transplantation (DEPT), Dino Ferrari Centre, University of Milan, Milan 20122, Italy

*Corresponding authors at: Department of Biosciences, University of Milan, Milan 20133, Italy.

** Corresponding author at: Department of Neuroscience Rita Levi-Montalcini, University of Turin, Turin 10126, Italy.

E-mail addresses: dario.besusso@unimi.it (D. Besusso), elena.cattaneo@unimi.it (E. Cattaneo), annalisa.buffo@unito.it (A. Buffo).

1 co-first authors

2 co-second authors

3 co-last authors

¶ ARTICLEINFO

Keywords:

Stem cell therapy

Neurodegeneration

Huntington’s disease

Cell transplantation

MSN (Medium Spiny Neurons)

Striatum

¶ ABSTRACT

Huntington’s disease (HD) is a fatal neurodegenerative disorder caused by a CAG repeat expansion in the HTT gene. This leads to progressive loss of striatal neurons and motor-cognitive decline. While current gene-targeting approaches aiming at reducing somatic instability show promise – especially in case of early treatment – they cannot restore the already compromised neuronal circuitry at advanced disease stages. Thus, cell replacement therapy offers a regenerative strategy to rebuild damaged striatal circuits. Here, we report that human striatal progenitors (hSPs) derived from embryonic stem cells via a morphogen-guided protocol survive long-term when transplanted into a rodent model of HD and recapitulate key aspects of ventral telencephalic development. By employing single-nucleus RNAseq of the grafted cells, we resolved their transcriptional profile with unprecedented resolution. This has identified transcriptional signals of D1- and D2-type medium spiny neurons (MSN), Medial Ganglionic Eminence (MGE) and Caudal Ganglionic Eminence (CGE) -derived interneurons, and regionally specified astrocytes. Moreover, we demonstrate that grafted cells undergo further maturation 6 months post-transplantation, acquiring the expected regionally defined transcriptional identity. Immunohistochemistry confirmed stable graft composition over time and supported a neurogenic-to-gliogenic switch posttransplantation. Multiple complementary techniques including virus-based tracing and electrophysiology assays demonstrated anatomical and functional integration of the grafts. Notably, chemogenetic modulation of graft activity regulated striatal-dependent behaviors, further supporting effective graft integration into host basal ganglia circuits. Altogether, these results provide preclinical evidence that hSP-grafts can reconstruct striatal circuits and modulate functionally relevant behaviors. The ability to generate a scalable, molecularly defined progenitor population capable of in vivo functional integration supports the potential of hSPs for clinical application in HD and related basal ganglia disorders.

¶ 1. Introduction

Huntington’s disease (HD) is a fatal, autosomal dominant neurodegenerative disorder caused by a CAG repeat expansion in the HTT gene leading to the progressive loss of striatal projection neurons and severe motor, cognitive, and psychiatric dysfunction [1]. Among the most affected neuronal populations are the striatal projection medium spiny neurons (MSNs), which constitute over of human striatal neurons and are central to the regulation of basal ganglia circuitry.

Emerging therapeutic approaches aiming at reducing the levels of mutated HTT (mHTT) based on the use of antisense oligonucleotides (ASOs) [2], RNA interference (RNAi), CRISPR-based gene editing [3,4], and small molecule splice variants modulators have shown promise in preclinical and early clinical studies [5]. However, these approaches face significant challenges, including allele specificity, off-target effects, and delivery constraints, particularly significant for deep brain structures such as the striatum. Moreover, none of these strategies directly address the restoration of the neuronal architecture and connectivity of the basal ganglia lost during disease progression.

Cell replacement therapy offers a potentially restorative approach for neurodegenerative conditions such as Parkinson’s disease (PD) and HD by aiming at replacing damaged neuronal populations and partial restoration of functional striatal circuitry. Proof-of-concept for this strategy has been established for PD through initial clinical and preclinical studies employing human fetal progenitors obtained from the ventral mesencephalon, with some individuals exhibiting remarkable long-lasting improvements in motor symptoms [6]. However, variable outcomes, together with ethical, logistical, and standardization concerns, have limited its scalability and reproducibility [6,7]. In recent years, advances in human pluripotent stem cell (hPSC) differentiation protocols have enabled the generation of neurons in vitro with MSN characteristics and increasing fidelity [8,9]. Nevertheless, important questions remain regarding the long-term identity, functional integration, and phenotypic impact of these grafts - issues that are fundamentally relevant for their therapeutic application.

We previously developed a differentiation protocol based on temporal exposure to morphogens and small molecules recapitulating Lateral Ganglionic Eminence (LGE) development and enabling the generation of D1- and D2-type striatal MSN progenitors in vitro [8]. These human striatal progenitors (hSPs) exhibit key transcriptional hallmark and striatal characteristics within 25 days in vitro (DIV). In the present study, we investigated the in vivo maturation, integration, and functional contribution of these hSPs following transplantation into a chemically lesioned rodent model of HD.

Using single-nucleus transcriptomics, we provide a high-resolution molecular characterization of the grafts, revealing enrichment in MSNs as well as the emergence of diverse interneuron subtypes and astrocytes. In parallel, we assessed circuit-level integration through anatomical tracing and analysis of spontaneous and evoked neuronal activity. Finally, we demonstrate that chemogenetic modulation of hSPgraft activity alters motor behavior, providing direct evidence of functional engagement with the host striatal circuitry.

These findings establish that LGE-patterned progenitors not only acquire a striatal identity post-transplantation but also form integrated grafts capable of influencing the behavioral response of the animals, reinforcing their potential for future clinical application in HD.

¶ 2. Materials and methods

¶ 2.1. hESC maintenance

The hESC H9 line (WiCell) was cultured on dishes coated with Cultrex , Trevigen) in complete mTeSR1 medium (StemCell Technologies, 85850) and maintained for up to three months with daily medium changes. For passaging, cells were dissociated twice a week using PBS (Euroclone, ECB4053) supplemented with EDTA (Sigma-Aldrich, 324506).

¶ 2.2. hESC striatal differentiation

hESCs were differentiated into striatal neurons as previously described in [8]. Briefly, cells were plated at a density of cells on Cultrex-coated plates in complete mTeSR™1 medium supplemented with ROCK inhibitor Y-27632 (RI; StemCell Technologies, 72307). For neuronal induction cells were subjected to Dual-SMAD inhibition using SB431542 and LDN193189 (StemCell Technologies, 72234 and 72149), in DMEM/F12 (Life Technologies, 11320033) supplemented with N2 (Life Technologies, 17502048) and B27 without retinoic acid (RA; Life Technologies, 17504044) for a total of 12 days. Starting on DIV5, recombinant human SHH C-25 II (R&D Systems 464‑SH) and DKK-1 (PreproTech, 120‑30‑10UG) were added to the culture and maintained until DIV25. On DIV21, cells were dissociated into single cells using Accutase (StemCell Technologies, 07920) and replated at a density of onto plates coated either with Matrigel GFR (StemCell Technologies, 354230) or Biolaminin 521 , Voden, LN521‑02) for continued culture. Cells were then maintained in DMEM/F12 supplemented with N2, B27 with RA (Life Technologies, 17504044), and BDNF (PreproTech, 450–02–10UG) until the end of the differentiation protocol (DIV35).

¶ 2.3. In vitro cell counting

At key stages of differentiation (DIV 5, 15, and 35), cells were fixed with cold paraformaldehyde (PFA) and subjected to immunofluorescence staining for markers indicative of MSN fate acquisition. Images were acquired using a Leica SP5 confocal microscope at magnification. Image analysis was performed using ImageJ software, through customized processing pipelines developed for each specific marker to enhance image quality and quantify marker-positive cells. The image processing workflow included contrast enhancement, saturation normalization (set at 0.35), edge detection of regions of interest (ROIs), background subtraction using a 10-pixel rolling ball radius, conversion to binary masks, hole filling, and particle analysis restricted to a size range of 20–300 pixels. DAPI staining was used to refine and validate cell segmentation. This methodology enabled accurate detection and quantification of marker-positive cells, with average counts per biological and technical replicate reported as follows: Hoechst ${ \sim } 6 0 0 $ ), GABA , DARPP32 ), CTIP2 , SIX3 , ISLET1/3 , mCherry , and HA .

¶ 2.4. Generation of Bi-DREADD hESC cell line

To engineer hESC H9 in order to introduce the bidirectional chemogenetic system Bi-DREADD [10], a total of viable cells were nucleofected using the Human Stem Cell Nucleofector Kit Solution Supplement 1; Lonza, VPH‑5022) with each of the plasmids AAVS1-TALEN-L (Addgene $# 5 9 0 2 5 $ , AAVS1-TALEN-R (Addgene #59026), and AAVS1-pur-CAG-Bi-DREADD (Addgene #159457). Nucleofection was performed using the B-016 program. Post-nucleofection, cells were plated on Cultrex ^ \mathrm { \textregistered } -coated dishes in mTeSR™1 with RI and incubated at . Puromycin selection was initiated on day 6 for three days. Surviving colonies were dissociated and sorted via FACS (FACSAria III SORP), selecting mCherry-positive cells. Single mCherry-positive cells were seeded in 96-well plates for clonal expansion. Expanded clones were transferred to larger culture formats and maintained in mTeSR™1.

To assess the correct insertion of the cassette, genomic DNA was extracted using the NucleoSpin \textsuperscript { \textregistered } Tissue kit (Macherey-Nagel, 740952) from clones reaching confluence. PCR screening was performed with PrimeSTAR HS DNA Polymerase (Takara, R010A) using primers targeting the left and right junction regions of homology arms flanking the AAVS1 insertion site (Suppl. Table 3). PCR products were analyzed by electrophoresis to confirm targeted integration of the Bi-DREADD cassette.

¶ 2.5. Cloning of lentiviral plasmids expressing jGCaMP7f and GFP

For the production of lentiviral particles expressing the calcium indicator jGCaMP7f, the corresponding coding sequence was subcloned from Addgene plasmid using first the HindIII-HF (NEB, R3104S) restriction enzyme followed by blunting using T4 DNA polymerase (NEB, M0203S). The purified linearized plasmid was then digested using BamHI-HF (NEB, R3136S) and the final product isolated by gel extraction (Zymoclean, D4002). The receiving Addgene plasmid was digested with BamHI and PmeI (NEB, R0560S) and purified by gel extraction. of linearized were ligated with water as control or with of blunted insert using T4 ligase (NEB, M0202S) overnight at . The following day, of the ligation product were transformed into One Shot™ TOP10 Chemically Competent E. coli competent cells (Thermofisher, C404003) with a shock at and the transformed bacteria spread into Ampicillin-embedded agar plates. Next day, four visible colonies were isolated and incubated in LB medium overnight for clonal expansion and miniprep purification (QIAprep Spin Miniprep Kit, 27106) the following day. Miniprep extractions were digested with BamHI and EcoRI-HF (NEB, R3101S) and digestion products run into agarose gel to confirm fragment insertion. Plasmids of positive clones were verified by Sanger sequencing and further expanded for large scale plasmid isolation.

A similar procedure was followed to clone the eGFP sequence into the identical backbone, starting by digesting the Addgene plasmid with AgeI and PmeI to remove the RFP coding sequence. The eGFP sequence was obtained by enzymatic digestion from Addgene plasmid using NotI followed by fill-in blunting with T4 DNA polymerase and new digestion with AgeI. The eGFP fragment was isolated by gel extraction. Ligation using of backbone and of insert or water was run overnight at followed by transformation, clonal isolation, validation by enzymatic digestion and Sanger sequencing as previously described.

¶ 2.6. In vitro calcium imaging

Calcium imaging was performed at DIV35 on cells replated at DIV21 into a 24-well Ibidi plate. Cells were incubated with Fluo-4 AM (Invitrogen, F14201; 1:1000 in HBSS, GibcoTM, 14025–092), a calciumsensitive fluorescent dye. After removing the culture medium, of Fluo-4 solution was added per well, and the plate was incubated at for , followed by two HBSS washes. To stabilize the signal for live imaging, of HBSS was added, and the cells incubated at for an additional .

Recordings were acquired using a Nikon TiE/CREST Video-ConfocalSuperResolution microscope equipped with a 16-channel LED, environmental chamber , and a dry objective. Fluo-4 was excited at , and images were captured at 1 frame per second for per region. Basal activity was recorded for , followed by another of recording after the addition of CNO (Biotechne, 49236) and SALB (Biotechne, 5611) to assess ligand-evoked activity.

Raw videos were processed in Fiji (ImageJ), applying contrast enhancement (saturation ) and background subtraction rolling ball), then saved as AVI files for analysis in Calima software [11, 12]. Calima corrected for bleaching and identified Regions of Interest (ROIs) based on fluorescence intensity: frame averaging (2.00–18.00) and intensity thresholds (0.03–0.1) were used to isolate cell bodies. Fluorescence traces were normalized using a 30-second baseline, and fluctuations exceeding baseline variability were defined as calcium spikes. Spike data were exported as CSV files (rows timepoints; colum ; values or 1).

Spike analysis was performed using an RStudio pipeline with the tidyverse, ggplot2, and xlsx packages. The percentage of active ROIs and the Mean Firing Rate (spike count per ROI per time window) were calculated for both basal and post-ligands conditions.

Calima software was used to assess functional connectivity by analyzing the synchronicity of calcium events between ROIs. ROIs were considered connected if their events occurred within the same time window, were within one-third of the image diagonal, and had an oscillation similarity above 0.7. In the representative images the connected ROI are linked by a red line.

¶ 2.7. Animals and in vivo experimental procedures

The experimental procedures involving live animals were performed in strict accordance with the European directive (2010/63/EU), the Italian Law for Care and Use of Experimental Animals (DL116/92), and the University of Turin institutional guidelines on animal welfare and authorized by the Italian Ministry of Health (Authorization: 327/2020- PR). Additionally, the ad hoc Ethical Committee of the University of Turin specifically approved this study. All studies involving animals are reported in accordance with the ARRIVE guidelines.

Adult athymic nude male rats (Hsd:RH-Foxn1rnu, 200–250 g, 7–8 weeks old) were purchased from ENVIGO laboratories. After a two-week acclimatization period, the rats underwent a unilateral striatal lesion induced by the injection of quinolinic acid (QA; 0.12 M; each point;) at the stereotaxic coordinates : , , and , , . All surgical procedures were performed under deep general anesthesia obtained with isoflurane (Isoflurane-Vet , Merial Italy) vaporized in . Rats were transcardially perfused under deep general anesthesia (Isoflurane-Vet ). Successful lesions were confirmed by behavioral assessment in the apomorphine-induced rotational test and post-hoc histological inspection. Three-four weeks later, rats received a single cell suspension of DIV15 hSPs divided in two deposits at the stereotaxic coordinates (mm): , , . The AP location of graft injection targets the region with the most extensive MSN depletion, i.e., where the two lesion sites overlap. Grafted cells had been detached with Accutase (StemCell Technologies, 07920) and RI and resuspended in DMEM/F12 supplemented with N2 and B27 with RA at a concentration of total volume). QA injection and cell implantations were performed with a blunt needle of a Hamilton syringe (Neuros Syringe) at a controlled infusion rate of . A 2-minute pause was maintained between dorsoventral (DV) depositions, and the needle was left in place for an additional following the final injection before slow retraction.

For synaptic tracing experiments, hSPs were transduced two times at DIV10 and DIV12 with a synapsin1 (hSyn)-driven TVA-GP-GFP polycistronic lentiviral vector (Addgene, ) at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 2 in the presence of polybrene (SigmaAldrich, H9268) [10,13,14]. The lentiviral construct carries sequences for the expression of a synapsin promoter-controlled histone-tagged GFP, a TVA receptor (for selective infection by EnvA-pseudotyped ΔG-rabies virus, mRV, carrying an mCherry reporter), and glycoproteins that enable monosynaptic spreading of the mRV. One week before sacrifice, the transplanted rats received an intra-graft injection with a modified rabies virus (ΔG-RV, carrying an mCherry reporter to label afferent neurons synapsing onto the grafted cells at stereotaxic coordinates : , , and , , .

For in vivo calcium photometry experiments, hSPs were transduced two times at DIV10 and DIV12 with lentiviral particles encoding either the calcium indicator jGCaMP7f (LV-hSyn-jGCaMP7f, TU/ mL) or green fluorescent protein (LV-hSyn-eGFP, , used as a control for calcium-independent fluorescence emission, under the human synapsin promoter (Vector Builder, VB230110–1508fjn, pLV230110–1006asc) at a MOI of 10 in the presence of polybrene. After the surgery, the head wounds were sutured using nonabsorbable silk suture (size 4–0, with BB needle, Ethicon) and the animals were allowed to rest for the following days.

¶ 2.8. In vivo chemogenetic modulation of graft activity

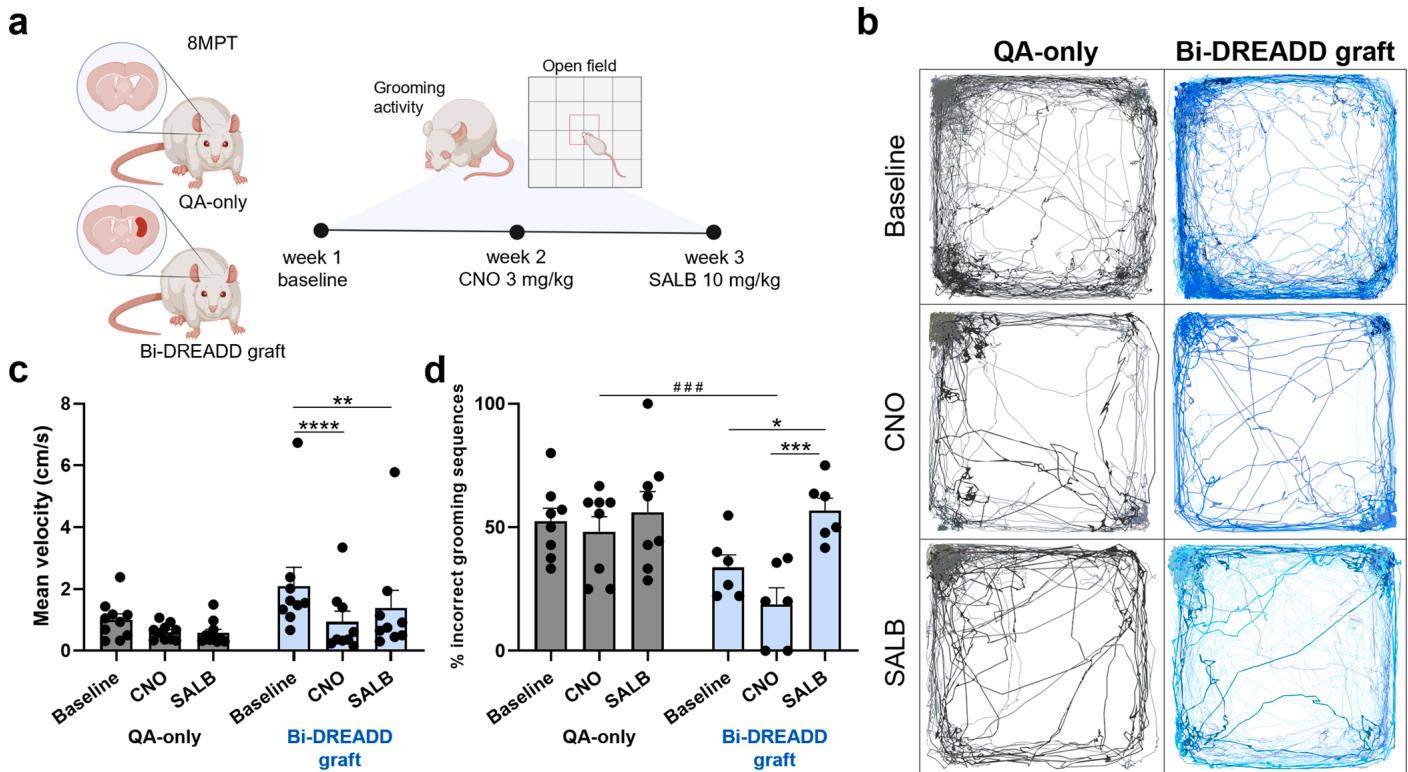

Since 6 months post transplant (6MPT), rats grafted with DIV15 BiDREADD hSPs and QA lesioned-only control rats were evaluated for their locomotion in the open field and grooming activity inside a glass -diameter cylinder at baseline and after the administration of the chemogenetic ligand CNO , Hello Bio, HB1807) and SALB , Hello Bio, HB4887). Each pharmacological treatment was performed with a one-week interval from each other to avoid drug interaction confounding effects. Behavioral tests were started 60 and after CNO and SALB administration, respectively. The QA-only group was composed of both sham rats ), injected with of cell resuspension medium (DMEM/F12 supplemented with N2 and B27 with RA), and empty Bi-DREADD grafts ).

Mean velocity and distance covered in the open field arena) over were measured with Ethovision ^ \mathrm { \textregistered } (Noldus). Rats were then video-recorded for in a glass cylinder test and correct and incorrect grooming sequences [15,16] were manually annotated.

Cytochemistry and immunohistological procedures

Cell cultures were fixed with ice-cold paraformaldehyde (PFA) for , permeabilized with Triton X-100 (Sigma-Aldrich, T8787) in PBS for and blocked with normal goat serum (Vector Laboratories, S-1000) for at room temperature. Cells were then incubated overnight at with primary antibodies (Suppl. Table 4). Appropriate Alexa Fluor-conjugated secondary antibodies (Life Technologies) were diluted 1:500 and mixed with Hoechst (Invitrogen, 33,342) to counterstain nuclei. Images were acquired on a Leica TCS SP5 Confocal laser microscopy (Leica Microsystems), using a oil immersion objective $\mathrm { \Delta } ( \mathrm { z o o m } = 1 . 7 ) $ ) guided by LAS-F software.

At 2 and 6MPT, rats were transcardially perfused under deep general anaesthesia, with saline solution, followed by cold PFA in phosphate buffer (PB, \mathrm { p H } 7 . 4 \AA . The brains were immediately dissected and postfixed for at . Then they were cryoprotected in sucrose (Sigma-Aldrich, S0389) in PB, embedded at in cryostat medium (Bio-Optica, 05–9801), and cryostat sectioned in 40 -thick coronal slices. The slices were stored in an antifreeze solution at until they were ready to be used. For in vivo calcium recording specimens, optrode was removed after perfusion and its placement was examined on -thick sagittal slices.

Immunofluorescence reactions were performed on floating brain sections incubated for at in a solution of 0.01 M PBS, , containing Triton X-100, normal donkey serum at the ratio of 1:20 and primary antibodies (Suppl. Table 4). When anti-CTIP2 primary antibody was used, antigen retrieval with Tris/EDTA at for was performed before primary antibody incubation. The sections were then incubated for at room temperature in a solution of 0.01 M PBS, that contains Triton X-100, normal donkey serum 1:20, secondary species-specific antibodies conjugated with Alexa Fluor dyes (Jackson Immunoresearch) and DAPI (Thermo Fisher Scientific, 62247). Slides were coverslipped with Mowiol (Sigma-Aldrich, 81381). Fluorescent tile-scan images of entire brain slices were acquired using the Axioscan 7 Microscope Slide Scanner (Carl Zeiss Microscopy). All images were collected using a ZEN confocal microscope LSM980 and ApoTome Axio Observer Z1 (Carl Zeiss Microscopy) microscope. ZEN Microscopy Software (Carl Zeiss Microscopy) and Fiji (ImageJ) software were used to adjust image contrast. The qualitative analysis of the distribution of migrated cells was performed by manual annotation based on microscope inspection of the position of HuNu-positive grafted cells, discriminating the ipsilateral and the contralateral hemisphere. For this purpose, we analyzed one -thick section every along the AP axis for each animal. Neurons were distinguished for the coexpression of doublecortin DCX.

¶ 2.9. Quantitative histological analysis

Graft volume was measured sampling one coronal slice every in animals sacrificed at 2 and 6MPT. The graft area in each slice was defined by the presence of high-density HuNu-positive cells. Graft survival was defined by the presence of a dense core of human cells identified by HuNu immunostaining or GFP reporter expression. Volume was interpolated using the Cavalieri method.

Cell density was computed as the number of HuNu-positive cells per . Graft expressions of Ki67, CTIP2, GABA, DARPP32 and SOX9 were quantified over the HuNu-positive population, sampling 2–3 fields per slice, 2–3 slices per graft. The average count for each marker over the HuNu-positive cells is reported as follow: 2MPT, cells over cells, cells over cells, cells over ${ \sim } 5 7 5 $ cells, cells over ~565 HuNu+ cells; 6MPT, cells over HuNu+ cells, cells over ~374 cells, cells over ~195 cells, CTIP2 + hDARPP32 cells over ~195 lls, cells over cells, cells over cells.

¶ 2.10. Analysis of graft input and output

In the viral-tracing analysis, images were acquired using an Axioscan microscope (Zeiss) and processed and analyzed using ImageJ (NIH). Neurons were assigned to specific brain regions based on the classifications from the Athymic Nude Rat Brain Atlas [17], using anatomical reference points in the sections visualized by DAPI. Multichannel immunofluorescence was performed to identify traced (mCherry-- positive GFP-negative) cells of the host (HuNu-negative) at extrastriatal sites. These cells were counted using ImageJ (NIH) in at least 35 slices per animal along the anteroposterior axis. Three series of brain sections were analyzed, with each series containing at least 11 sections, each spaced at intervals. The selected series started at specific anteroposterior coordinates: Bregma , and .

As regards graft output, the positive fractioned area (i.e. the percentage of positive pixels throughout the entire ROI) occupied by graftderived fibers in the striatal target regions of the brain was quantified over the nucleus area manually traced using ImageJ-Fiji software. Samples with donor migrated cells in the target regions have been excluded from this analysis.

¶ 2.11. Tissue clearing and light sheet imaging

The brain of an athymic adult rat, which was lesioned and received a graft of cells transduced with the synapsin1-driven TVA-GP-GFP (Addgene, ) polycistronic lentiviral vector, was processed for light sheet microscopy using the iDISCO clearing method [18], with an optimized de-lipidation step for rat brains [19].

The brain was divided by a midline sagittal cut, with each hemisphere processed individually. The hemispheres were washed in PBS/ , then in B1N buffer ( Triton X-100/Glycine/ NaN3) and dehydrated in a B1N/MeOH gradient (from to ). It was subsequently washed in MeOH, DCM, and MeOH, then rehydrated through a reverse B1N/MeOH gradient, followed by washes in B1N, SdC buffer NaN3/methyl -cyclodextrin), and PTwH (PBS/ TritonX- Tween-20/ Heparin/ NaN3). The sample was washed in PTx.2 Triton X-100) 4 times at room temperature, followed by overnight incubation in permeabilization solution (PBS/ Triton X DMSO/ glycine). After incubation in blocking solution (PBS Triton X-100/ donkey serum) at for , the sample was incubated with primary antibodies dilutions in donkey serum anti-GFP 1:100, and anti-RFP 1:1500 in PTwH containing DMSO and normal donkey serum at for 11 days with shaking. Following primary antibody incubation, the sample was washed in PTwH , then incubated at with secondary antibodies in normal donkey serum for 10 days. It was then washed in PTwH , with additional washes every hour during the day and left overnight. For tissue clearing, the sample was sequentially dehydrated in , , , , and MeOH (1 h per step), followed by MeOH overnight. It was then incubated in MeOH with shaking overnight, transferred to DCM, and finally cleared in dibenzyl ether (DBE). The cleared hemisphere was imaged using an Ultra Microscope II (LaVision Biotec), equipped with an sCMOS camera (Andor Zyla, model 5.5) and a objective lens (LaVision LVMI-Fluor ). Imaging was performed using two laser configurations with the corresponding emission filters: 680/30 for RFP and 525/50 for background and GFP. Zstack acquisition was carried out using InspectorPro software (LaVision Biotec) at intervals. To cover the entire hemi-brain, multiple overlapping stacks ( overlap) were acquired using a mosaic acquisition approach. For analysing and 3D reconstruction of traced cells, Arivis (Version 3.01) was used. Atlas regions of the rat brain [20] (https://www.ebrains.eu/brain-atlases/reference-atlases/rat-brain) were imported as 3D objects for compartmentalization. Intensity signals of the staining (GFP-positive for graft or RFP-positive/GFP-negative for traced primary afferent) were used in combination with volume threshold-based segmentation. Following segmentation, all objects to be compartmentalized were grouped and assigned to their corresponding atlas regions.

¶ 2.12. In vivo fiber-photometry

Fiber-photometry recordings were performed using the Time Correlated Single Photon Counting System (TCSPC, Becker Hickl GmbH), developed following Meng et al., [21]. Upon implantation in the brain of the rats, optrodes were tethered to the detector and laser via a multimode fiber optic patch cord. This patch cord delivered light from picosecond pulsed diode laser at (equivalent power measured at the end of the fiber) to excite the cell populations expressing the fluorophore, and the emitted photons were collected at via the same patch cord and conveyed to the detector. The detector consists of a photon multiplier of solid state that converts the fluorescence (photon counts) into electrical signals transmitted to the TCSPC recording system via the data acquisition card. Thus, the fiber-photometry allowed the study of graft-derived photons with a resolution-level of cell population.

For this approach, 6 rats received jGCaMP7f-hSPs and 4 GFP-hSPs grafts. They underwent surgery for optrode implantation 2 weeks before the start of recordings. The fiber tip (core diameter: ; length: , B&H) was implanted through a skull hole with the aim to target the upper region of the graft, at the stereotaxic coordinates (mm): , according to the [17]. Sterile mini scrubs and dental cement (Paladur) were used to secure and stabilize the implant to the skull.

Spontaneous calcium signals were recorded in rats freely moving in an open arena, condition referred as awake (AW, box dimension: ), or under deep anesthesia (AN, dose: ip, ketamine, xylazine [70 mg, , from 6 up to 10MPT. For each animal, we continuously recorded the graft activity in about 50 sessions in AW, 30 in anesthesia conditions, and 6 in FSK, with each recording lasting 608 s . Five animals (3 jGCaMP7f, 2 GFP) were discarded from the analysis due to several reasons: in two rats (1 jGCaMP7f, 1 GFP) the optrode was accidentally removed; one rat (jGCaMP7f) exhibited seizures and was therefore excluded from the study; in other case the graft was located outside the striatum, while and in the last GFP-rat, the optrode placement was not possible to be confirmed in the post-mortem histological analyses.

Moreover, traces used for the analysis were selected based on the assessment of trace stability (percentage of constant baseline photon detection, also called floor noise and signal quality (signal surpassing the noise level). Recordings with those noise signals persisting after the signal correction, present in more than of the total time, were excluded from the analysis (Fig. S5a). The foot-shock (FSK) traces were selected under the same criteria applied to the evaluation period of 3 s before and after the stimuli. Thus, for the analysis we end-up with an average of 25 recordings in AW, 22 in AN and 4–5 in FSK, per rat.

Evoked responses were elicited by application of FSK to rats showing spontaneous activity (jGCaMP7f-graft group) or significant fluorescence signals photons/second, laser power; GFP-graft group) in the open arena. Rats were habituated to the room-chamber without FSK stimuli, for 2 days (sessions of , each). The day of the test, rats were placed in the same shock box chamber (Habitest, Model H13–15). Each session began with a 2-min period without stimuli, followed by two electrical stimuli in intensity and of duration), delivered in pseudo-random intervals of 2–3-min (Fig. 4 g). Each rat received up to two sessions per day, until completing 5–6 sessions. Video recordings of were taken simultaneously to align the photometry signals with the stimulus time.

¶ 2.13. Analysis of the fiber-photometry calcium signals

¶ 2.13.1. Pre-Processing of raw traces

The fiber photometry signals were processed using a custom Matlab script (GSE302876). We first applied a low-pass (5 Hz) and a high-pass filter to the signal to correct for high-frequency noise and slow drifts, respectively, followed by a smoothing filter (time window of 1 s) to compensate for photobleaching. Then, to correct the variability between rats, we normalized the absolute fluorescent signals using , where is the mean signal of the entire recording.

¶ 2.13.2. Peak detection

Calcium transients (peaks) were detected using a heuristic method adjusted to our data (settings: minimum inter-peak interval , minimum prominence 0.5, threshold of 2.5 sd of the mean signal), which considers standard features used in calcium peak detection [22] [23,24] as well as specific jGCaMP7f properties [25].

The signal-features, maximal peak amplitude (relative to baseline and averaged in each recording after alignment to maximal peak amplitude) and frequency (detected over the first of each recording), were calculated between conditions and experimental group. For specific comparison in which the number of traces varied considerably across groups or conditions, the number of considered samples was determined by the smallest sample size and adjusted with an equivalent number of traces randomly selected from the larger groups.

¶ 2.13.3. FSK response analysis

Peak detection was performed as described above with the difference that normalization of the traces, F0 was calculated locally, over of the pre-stimulus signal, and then subtracted to the post-stimulus signal. Calcium transients were time-locked to the time of FSK for each group. The change in the average fluorescent signal was calculated within a 3-second time window before and after stimulus delivery (FSK response, stimulus locked condition). Responses from all animals to each stimulus were visualized using event-related heat maps. To confirm the specificity of FSK responses, the was also computed by aligning transients to random time points (random alignment condition) drawn from a uniform distribution.

¶ 2.13.4. MEA recordings on ex vivo brain slices

Neuronal activity was recorded using the BioCAM DupleX system (3Brain) with CorePlate™ 1 W 38/60 MEA chips. Bi-DREADD-grafted rats were decapitated under isofluorane anesthesia and transcardially perfused with NMDG-HEPES solution. -thick parasagittal brain slices of the ipsilateral hemisphere were sectioned with a cut angle of using a vibratome in carboxygenated NMDGHEPES solution at room temperature. Slices were then transferred to a recovery chamber filled with carboxygenated NMDG-HEPES solution. Slices were allowed to recover for at followed by an additional recovery in 1X normal Ringer solution at room temperature . Slices were then positioned onto a dry MEA chip to ensure optimal contact between the region of interest, such as the graft, and the electrodes. The on-chip amplification circuit allows for bandpass filtering conferred by a global gain of 60 dB sufficient to record fast oscillations. The MEA monowell was continuously perfused with 1X normal Ringer solution using a peristaltic or syringe pump at a flow rate between 2 and . The perfusion system included inlet and outlet tubing to ensure constant exchange of fresh medium and oxygenation. To reduce low-frequency noise introduced by the perfusion lines, grounding was applied to the tubing according to the manufacturer’s recommendations. At the beginning of the experiment, a digital image of the slice was taken through a stereomicroscope. During the post-hoc analysis the digital image was overlayed on the activity map to identify the graft and host areas in the slice. After positioning the slice, the system was perfused with 1X normal Ringer solution for at least to allow stabilization and observation of basal activity. This was followed by perfusion with DA for , then washed with 1X normal Ringer for . Subsequently, CNO or SALB for to verify responsiveness. Raw data were analyzed with BrainWave software (3Brain). Spike detection was performed using the PTSD (Precise Timing Spike Detection) algorithm, with the detection threshold set at seven times the standard deviation of the baseline signal on each electrode [26]. Signals were high-pass filtered at to isolate multiunit activity. Bursts were identified using a time-based burst detection algorithm that defined a burst as a minimum of three consecutive spikes occurring within a maximum interspike interval of . Only active electrodes—those recording consistent spiking activity—were included in the burst analysis. To ensure accurate anatomical localization of recorded signals, the electrophysiological data were spatially mapped onto the slice morphology by superimposing brightfield images taken prior to the recording session onto the electrode layout. This allowed for precise correlation between spike activity and the graft region of interest.

¶ 2.13.5. Nuclei Isolation and snRNAseq

Graft cores were dissected from rat striatum samples from rats at 6MPT) and flash frozen. Similarly, hSPs were detached for the plate at the desired time point, flash frozen and conserved at until processed for snRNAseq. Nuclei isolation and sample preparation for snRNAseq were performed following the procedure described in Fiorenzano et al. [27]. Briefly, for nuclei isolation samples were thawed on ice and transferred in a glass douncer with of nuclei lysis buffer sucrose; 6 mM ; MgAc; 0.1 mM ; Tris_HCl, ; 1 mM DTT; Triton X) supplemented with 0.4 of RNAse inhibitors (Ambion and SUPERase In, Invitrogen) on ice. The tissue was homogenized into a nuclei suspension using a loose-fitting pestle (10 strokes), followed by a tight-fitting pestle (additional 10 strokes) and then centrifuged at for at 4 The resulting nuclei pellet was resuspended in of cold wash buffer, depending on pellet size. The buffer consisted of RNAse-free PBS supplemented with BSA (fraction V), RNase inhibitors (Ambion™ and SUPERase , Invitrogen) and DRAQ7 (1:1000; BD Bioscience, cat. No. 564904). Nuclei were subsequently purified by fluorescence-activated nuclei sorting (FANS) on a FACSAria III cell sorter (BD Biosciences) equipped with a nozzle. Sorting was performed based on DRAQ7 staining and event size (forward and side scatter). For snRNAseq, 12000 nuclei per sample were collected into BSA-precoated DNA LoBind tubes (Eppendorf) before single-nucleus library preparation. Single nuclei were captured using the Chromium Single Cell 3 ´Chips (10X Genomics, cat. no. PN-120233, v3.1) loaded with master mix and barcoded beads. After pooling and amplification, the quality of the resulting libraries was checked by a Bioanalyzer (DNA HS kit, Agilent) and sequencing was performed on an Illumina NovaSeq 6000 in 100 bp paired-end mode.

¶ 2.14. Bioinformatics

¶ 2.14.1. snRNA-seq data pre-processing

A total of 34874 nuclei from four rats were sequenced. Sequencing reads from snRNA-seq were quality filtered, trimmed and aligned to the reference genome with nf-core scrnaseq pipeline v2.5.1, based on Nextflow workflow manager [28]. The pipeline first checks the quality of sequencing reads with FastQC v0.12.1 (https://www.bioinformatics.ba braham.ac.uk/projects/fastqc/) and then aligns sequencing reads to the reference genome with Cell Ranger (v7.1, 10X Genomics). Specifically, CellRanger exploits STAR v2.7.2a aligner [29] to align sequencing reads to a customized reference genome obtained merging Homo sapiens (hg38) and Rattus norvegicus (R6.0) assemblies and filters alignments with Samtools v1.17.0 [30]. The adopted reference genome enables the identification of the species of origin for each cell, allowing it to retain only human cells. Moreover, the pipeline identifies Cell Barcode (CB) and Unique Molecular Identifier (UMI) for each read, eventually producing a matrix that reports molecule counts for each gene and each cell.

¶ 2.14.2. Environmental RNA removal, cells selection and QCs

All downstream analyses were performed using the Seurat v5.0.1 on the 17679 nuclei of human origin. Count matrixes were imported in R v4.3.1 environment with Read_10X function and counts were corrected to account for the presence of environmental RNA with DecontX [31], contained in the celda package v1.18.1., by exploiting RNA transcripts detected in empty (cell-free) droplets. For each sample, the distributions of the number of expressed genes, of total counts and of percent mitochondrial RNA for each cell were evaluated. Only cells with a number of total RNA counts in the range 300–30,000 (300–20,000 for in vitro samples), a number of expressed genes in the range 300–6000 and mitochondrial RNA transcripts lower than were retained. A total of 17,366 and 10,218 cells were retained for graft and in vitro samples, respectively.

¶ 2.14.3. Normalization and dimensionality reduction

Data normalization, scaling and highly variable features selection was performed with SCTransform function, retaining the 3000 most highly variable genes (HVGs), which were expressed in at least 5000 cells. Linear dimensionality reduction was achieved through principal component analysis (PCA) by exploiting RunPCA function. By examining the Elbow plot, 50 and 30 principal components (PCs) were retained for subsequent analyses for the graft and in vitro samples, respectively.

¶ 2.14.4. Non-linear transformation and batch integration

The Harmony [32] batch correction integration method of the RunHarmony function was utilized to remove technical variability among samples. The selected principal components were used to perform non-linear dimensionality reduction employing the RunUMAP function. Cell cycle status was inferred with the CellCycleScoring function exploiting a curated list of known cell cycle marker genes. The Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection (UMAP) was then plotted with DimPlot and FeaturePlot functions to check for even distribution of cells based on the sample of origin and features of interest, respectively.

¶ 2.14.5. Clustering and manual annotation

The Louvain algorithm, as implemented in the FindNeighbors function, was utilized to cluster cells based on their similarity in gene expression profiles. To set cluster granularity, resolution parameters of 0.65 and 0.25 were selected for the graft and in vitro samples, respectively. To annotate the identified cell clusters, a manually-curated marker-assisted approach was adopted by examining the expression of known marker genes taken from literature, enabling the assignment of the accurate cell types to each cluster. Following grafted cells annotation, subsequent analyses including normalization and both linear and non-linear dimensionality reductions were performed on the neural populations only (excluding astrocytes).

To double-check the obtained annotation, differentially expressed genes (DEGs) within each cluster were identified, by using FindAllMarkers function. Genes were considered as differentially expressed if they exhibited a log fold change (logFC) in module greater than 0.25, an adjusted p-value below 0.05 and were expressed in at least of cells . Moreover, among these markers, only the positive ones (i.e., up -regulated) were retained . The expression of the top 30 and 50 differentially expressed genes exhibiting the highest logFC for each cell type in the graft and in vitro samples, respectively, were plotted as a heatmap using DoHeatmap function.

¶ 2.14.6. Spatial mapping analysis

The neural subset of the graft-derived cells was used to perform an in silico spatial mapping analysis. This process consisted of mapping our data onto a publicly available adult mouse brain spatial transcriptomics dataset generated with the 10X Genomics Visium platform (https /www.10xgenomics.com/datasets/mouse-brain-serial-section-1-sagi ttal-anterior-1-standard-1–0-0). Both linear and non-linear dimensionality reductions were performed and based on the elbow plot, the first 50 principal components were retained for the clustering of spatial transcriptomics spots.

To enable cross-species genes integration, mouse genes were converted to their corresponding human orthologs with the toupper function. Only genes shared between the two datasets were retained for the subsequent anchor-based integration workflow through FindTransferAnchors and TransferData functions. The k for the k-nearest neighbor algorithm was set to 20 (k.anchor ) and 50 dimensions were selected for the anchors identification process.

¶ 2.14.7. Single-cell integration analysis

Count matrices of neuronal cells from Siletti et al. [33] - excluding cells annotated as Neuronal Splatter - were subsampled in order to obtain at most 8000 cells for each supercluster_term metadata class, which contained the information on the neuron type of the dataset used as reference. Subsequently, cells were imported in Seurat environment, merged with the neural subset of our dataset and preprocessed (see above). Cells from both datasets were represented as a single UMAP and the reciprocal regionalization of grafted and adult cell types was evaluated. To obtain a more quantitative measurement of pairwise similarity across grafted and adult cell types, a label transfer analysis was performed. Specifically, datasets were normalized using the NormalizeData function, PCA was calculated with 30 dimensions, 3000 integration anchors were calculated and labels from supercluster_term were transferred. We used the R package pheatmap to generate the probability heatmap depicting the mean similarity score of each neuronal group to each class of supercluster_term. In regard to the astrocytic component, label transfer of the astrocytic subset of the Siletti et al. [33] dataset was performed. The label transfer, performed as described above, scored cells based on the annotation contained in the region metadata column, containing information on the anatomical region of collection of astrocytes in the dataset. Subsequently, datasets were normalized using the NormalizeData function, PCA was calculated with 30 dimensions, integration was performed with the method CCAIntegration and then UMAP was calculated to represent cells in a single UMAP.

¶ 2.15. Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses were performed with GraphPad Prism 8.0 software (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA). All data were subjected to statistical evaluation for the identification of outliers using the robust ROUT method ), which was applied prior to subsequent analyses. Outliers identified through this approach were excluded to ensure data integrity and analytical consistency. Results were deemed to be statistically significant when p was ; , , . All details of statistical analyses are reported in the dedicated table (Suppl. Table 5).

¶ 3. Results

¶ 3.1. In vivo maturation of hSP-grafts recapitulates ventral telencephalic trajectories, including striatal and gliogenic lineages

We have previously shown that functional MSNs can be generated within DIV25 through a morphogen-guided protocol [8], supporting their use in cell replacement therapy for HD. To investigate their developmental potency in vivo, these hSPs were grafted at DIV15 into the quinolinic acid (QA)-lesioned striatum of athymic rats. Gross anatomical evaluation revealed that a large proportion of grafts over 6 independent experiments) survived for up to 2–10 months post-transplantation, reflecting strong resilience and adaptation within the host lesioned striatum (Suppl. Table 1).

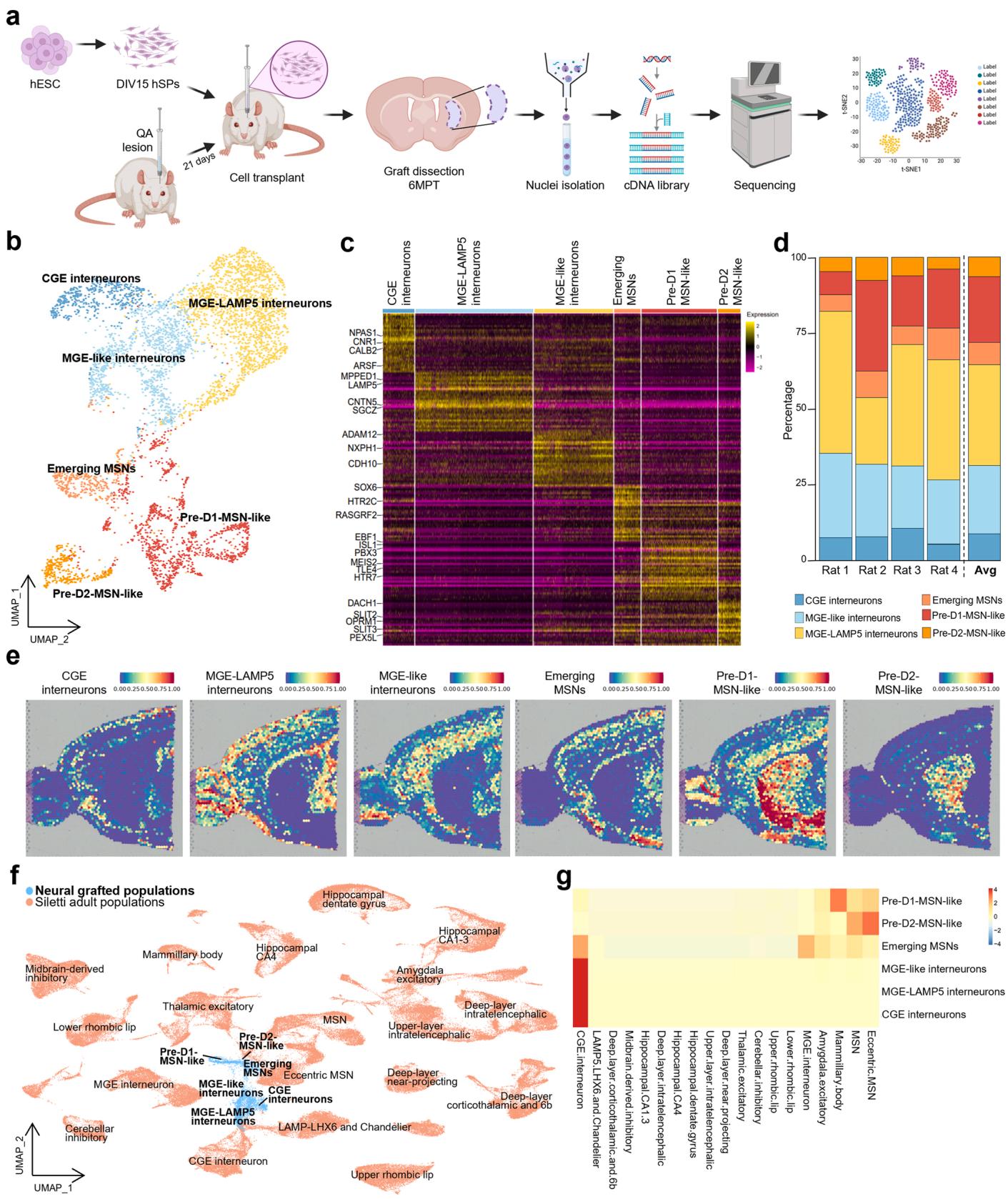

At 6 MPT the matured hSP-graft core - the primary graft mass located in the striatum - was isolated and prepared for single-nucleus RNA sequencing (snRNAseq) (Fig. 1a). Approximately 35000 nuclei from four rats were sequenced, of which 17679 were identified as being of human origin and retained to characterize the grafts. This high-resolution transcriptional analysis uncovered diverse neuronal and glial populations. These were identified via manual annotation using established marker genes (Fig. 1c, S1d) as visualized by Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection (UMAP) and dot plot (Fig. 1b; S1a-2b), with consistent profiles across four different grafts (Fig. 1d, S1b). Subclustering of the neuronal component revealed on average a predominant D1-MSN population of neurons), and a D2-committed MSN precursor population $( 6 . 3 8 % $ Fig. 1b, d). Moreover, we identified multiple interneuron subtypes transcriptionally aligned with MGEderived lineages, which collectively accounted for of neurons, including a prominent population of LAMP5-expressing MGE interneurons . In addition, CGE-derived interneurons represented of the neuronal population (Fig. 1b, d). Label transfer analysis of snRNA profiles onto mouse spatial transcriptomic datasets confirmed striatal localization of D1- and D2-MSNs, and cortical positioning of MGE- and CGE-derived interneurons (Fig. 1e). Moreover, comparisons with an adult human single-cell dataset [33], revealed a strong transcriptional similarity with authentic human MSNs (Fig. 1f, g), while graft-derived CGE and MGE interneurons more closely resembled adult CGE interneurons and LAMP5-LHX6 and Chandelier adult population respectively, validating their identity (Fig. 1f).

Fig. 1. snRNAseq of hSP-grafts, (a) Graphical representation of the snRNAseq workflow. UMAP of neural grafted cells colored by cell type. (b) Heatmap representing the expression of the top 30 differentially expressed genes exhibiting the highest logFC for each cell type in the graft samples. © Bar graph representing the neuronal cell type proportions of the grafted cells in the four rats analyzed and the relative average. (d) Label transfer visualization of the neuronal grafted cells onto a Visium adult mouse brain spatial transcriptomics dataset divided by cell type. (e) UMAP plot colored by dataset of origin, illustrating the integration of neuronal graft data from this study with that of a published human brain snRNAseq dataset derived from adult healthy individuals [10]. (f).Heatmap showing the similarity scores between grafted and human adult [10] neurons upon label transfer.

In addition to neuronal populations, snRNAseq revealed that on average of the grafted cells exhibit a non-neuronal, astroglial identity (Fig. S1a, f), confirmed by expression of established glial markers, such as AQP4, GFAP and SLC1A3 (Fig. S1c, d). The presence of astrocytes in long term grafts mirrors findings from human dopaminergic cell transplants in rat models of PD [10,13].

To refine the identity of this astroglial population, we scored cells against a curated astrocyte gene set (436 genes, [34], Fig. S2a, Suppl. Table2), revealing six distinct astroglial subclusters (Fig. S2b). Spatial label transfer onto mouse Visium datasets showed that subclusters 0, 2, 3, and 4 carried striatal signatures, whereas subclusters 1 and 5 aligned with cortical regions. An olfactory bulb signature was also detected in subclusters 0, 1, and 3 (Fig. S2c). Mapping onto the adult human astrocyte dataset [33] confirmed regional striatal identity in subclusters 0 and 4 and also revealed similarities with pallial and diencephalic structures (Fig. S2d, e). Collectively, these findings indicate that graft-derived astrocytes predominantly adopt a telencephalic, and in many cases, striatal regional identity.

To investigate whether the observed cellular heterogeneity was already present in vitro within the hSP cell preparation, we performed snRNAseq on the same batch of hSPs used for transplantation. Upon differentiation according to [8] (Fig. S3a), these cells showed the capacity to develop into mature MSNs in vitro (Fig. S3b). At DIV15 – the time of transplantation – the cell population consisted primarily of homogeneous neural progenitors (Fig. S3d-g). By DIV35, however, we observed the emergence of MGE- and GE-like precursors as well as early MSNs (Fig. S3d-g). Notably, a small but distinct subpopulation expressed glial markers such as SOX9, SOX10, S100B, OLIG2 and GFAP (Fig. S3c), suggesting that glial progenitors were already present at this in vitro time point. We cannot exclude that these cells contributed to the astrocytic population found at 6MPT.

Altogether, these findings demonstrate that hSP-grafts undergo in vivo maturation along ventral telencephalic trajectories, giving rise to a regionally organized and molecularly diverse architecture composed of striatal projection neurons, interneurons, and astrocytes. This developmental progression includes a neurogenic-to-gliogenic switch and trajectories only partially captured by in vitro differentiation, underscoring the role of the host environment in promoting graft maturation and complexity.

¶ 3.2. Long-term in vivo maturation of hSPs reveals progressive acquisition of striatal identity and gliogenic potential

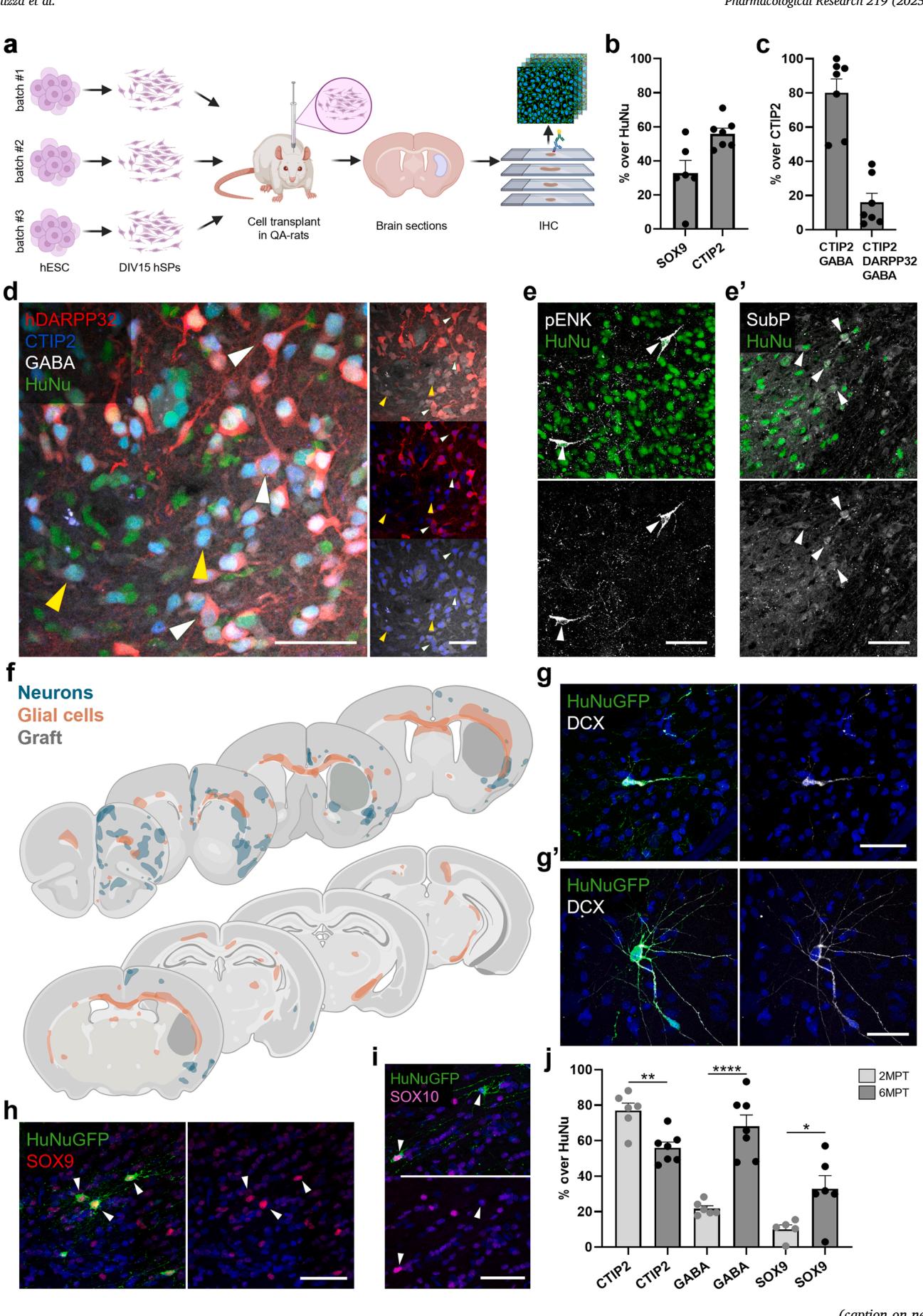

Long-term snRNAseq analysis revealed a graft composition including MSNs, interneurons and astrocytes, reminiscent of the endogenous striatal cellular profile. To corroborate and complement these transcriptomic findings, we performed immunohistochemical analyses on samples from three independent experiments at 6MPT (Fig. 2a). Overall, the graft core consistently maintained stable volume (Fig S4a, d) and cell density (Fig S4b), with negligible proliferation detected (Fig. S4c).

Immunolabelling for the astrocytic transcription factor SOX9 confirmed the presence of a glial population, comprising of grafted cells (Fig. 2b; Fig. S4e). We next focused on the neuronal compartment, as transcriptomic data had indicated widespread expression of CTIP2 (BCL11B) and GABA markers across graft-derived neurons (Fig. S1e). Immunostaining revealed minimal overlap between SOX9 and CTIP2 and identified CTIP2-positive neurons within the graft Fig. 2b). Of these, co-expressed GABA (Fig. 2c, d), and were triple positive for CTIP2, GABA and DARPP32, indicative of mature MSNs (Fig. 2c, d). Expression of substance (SubP) and pro-enkephalin (pENK), known to be expressed in D1- or D2-MSNs, respectively, further supported transcriptomic evidence indicative of the presence of both MSN subtypes at 6MPT (Fig. 2e, e’). Collectively, these findings confirm the long-term presence of MSNs, MGE-derived interneurons, and astrocytes within the graft core, with concordance between transcriptomic and protein-level identities, consistently observed across experimental replicates.

In line with the presence of interneurons and glial cells, we also observed substantial migration from the graft into the host parenchyma, with some inter-animal variability (Fig. 2f; Fig. S4f). Migrating neurons expressed doublecortin (DCX), a marker of immature migratory neurons, and exhibited both migratory and more differentiated morphologies (Fig. 2g, g’). These cells preferentially colonized the rostral neocortex, reaching upper layers (Fig. 2f; Fig. S4f). Glial cells expressing SOX9 (astroglial lineage) or SOX10 (oligodendroglial lineage), were also detected along distinct migratory trajectories (Fig. 2h, i), primarily occupying white matter tracts and dispersing both rostrally and caudally – including the contralateral hemisphere (Fig. 2f). This migratory behavior reflects the active integration of hSP-grafts in the host brain.

snRNAseq of in vitro differentiated hSPs revealed the presence of a small subset of gliogenic progenitors, supporting the emergence of glial populations in vivo (Fig. S3c). To investigate the progression of this gliogenic potential, we analyzed graft core composition over time. At 2MPT, approximately of grafted cells expressed CTIP2, while only were SOX9-positive. By 6MPT, the SOX9-positive population had tripled, coinciding with a one-third reduction in CTIP2- positive cells and a threefold increase in GABAergic neurons (Fig. 2j). Altogether, these findings suggest that hSPs continue to mature into neurons over time while simultaneously activating an intrinsic gliogenic program in response to the in vivo environment.

¶ 3.3. Transplanted cells exhibit integration into the host striatal circuitry

To investigate the potential of hSP-grafts in reconstructing lost striatal circuitry, we examined their ability to receive afferent inputs from anatomically appropriate regions and to project toward canonical striatal targets.

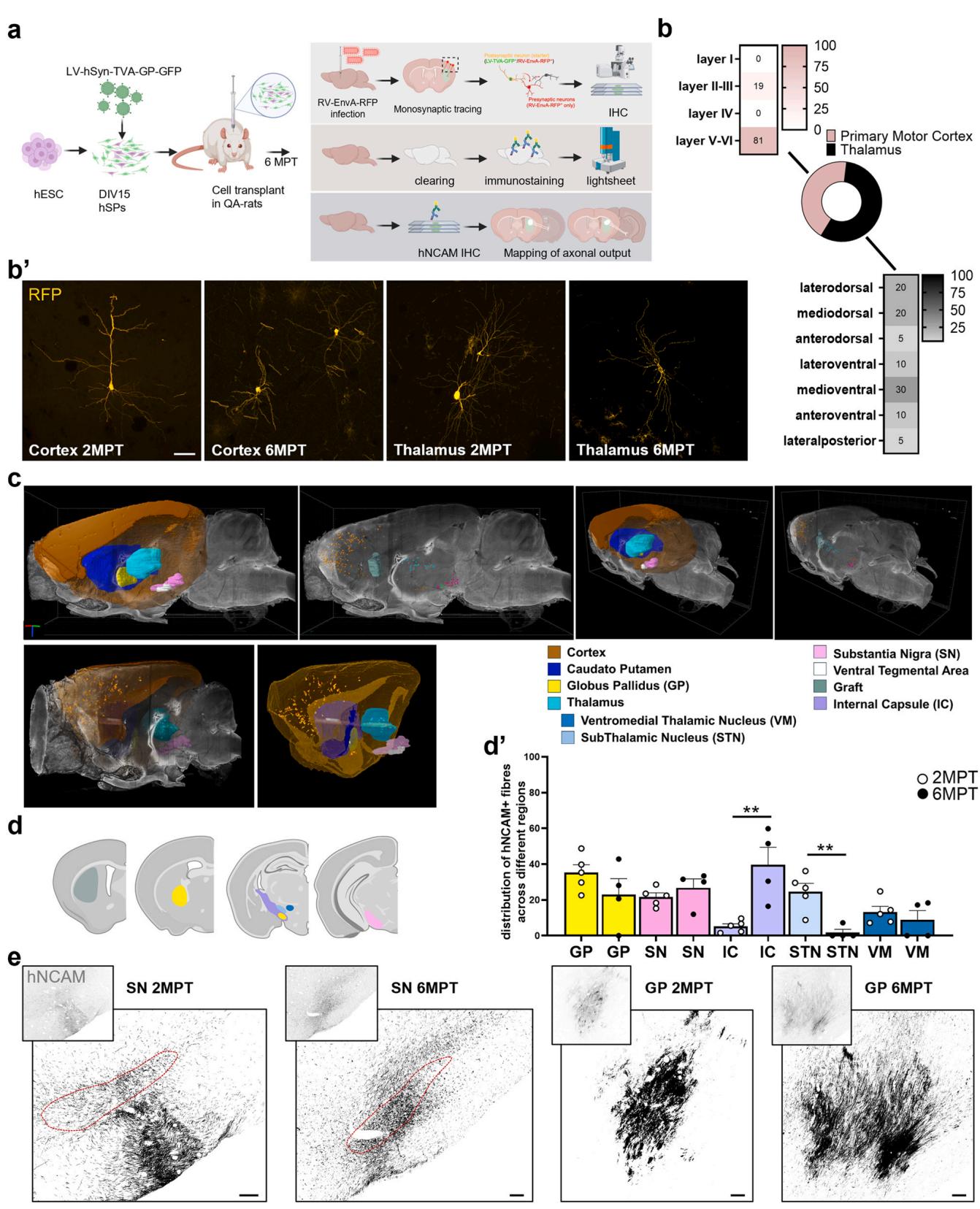

Host-to-graft connectivity was studied using a retrograde monosynaptic tracing approach based on mutant rabies virus (Fig. 3a; [10, 14]). At 2MPT, host afferent neurons were identified in extra-striatal regions across all five analyzed brains, based on immunohistochemical analysis of serial sections, indicating early and robust integration of hSPs into long-range host circuits. Host-traced inputs were primarily localized in the ipsilateral motor cortex and thalamus (56.8 $\pm 8 . 8 7 % $ , both of which project to the striatum (Fig. 3b). Within the cortex, the majority of labeled afferents were found in the deep layers (V–VI), with the remainder in upper layers (II–III) (Fig. 3b), consistent with the laminar distribution of endogenous corticostriatal neurons projecting to the striatum. At 6MPT, two grafted rats were analyzed and host afferents were again identified in cortical and thalamic regions, showing a distribution similar to the earlier time point and suggesting stability of graft connectivity over time (Fig. 3b’).

To gain a more comprehensive overview of afferent sources, we cleared the brain of one grafted rat 6 MPT and imaged the graft connectivity. This analysis confirmed inputs from the cortex and thalamus and additionally revealed afferent projections from the substantia nigra (SN), globus pallidus (GP) and ventral tegmental area (VTA; Fig. 3c, Suppl. Video 1). This observation highlights the advantage of wholebrain clearing and imaging, which reduces the risk of incomplete detection of structures typically associated with conventional sectionbased sampling methods. Nevertheless, we cannot exclude the influence of inter-animal variability.

To investigate graft-to-host innervation, we mapped hNCAMpositive axons across the antero-posterior axis at 2MPT. Projections from the transplanted cells reached multiple basal ganglia targets, including the SN and GP , which are major targets of the direct and indirect striatal pathway, respectively (Fig. 3d, e). Additional human axons also reached indirect striatal targets, such as the subthalamic nucleus (STN; and the ventromedial thalamic nucleus (VM; . At 6MPT, projections to SN, GP, VM remained relatively stable over time (26.8 ; ; , respectively), while a marked reduction was observed in projections to the STN 1 (Fig. 3d, e). Notably, this was accompanied by a corresponding increase in hNCAM-positive axon density within the internal capsule (IC; 2MPT: ; 6MPT: , suggesting that some graftderived axons may follow pre-existing white matter tracts.

Fig. 2. Long-term in vivo characterization of hSP-grafts. (a) Schematic illustration of the experimental workflow for the immunohistochemical characterization of

hSP-grafts at 6MPT. (b) Quantification of the fraction of grafted cells, identified by HuNu staining, expressing the astrocytic marker SOX9, and the neuronal

transcription factor CTIP2. © Quantification of the fraction of CTIP2/GABA and CTIP2/GABA/hDARPP32 positive hSPs grafted cells over the CTIP2/HuNu pop

ulation. (d) Representative image of CTIP2/GABA/HuNu (yellow arrowheads) and hDARPP32/CTIP2/GABA/HuNu (white arrowheads)-expressing cells in the graft

core. (e) Representative images of SubP (e) and pENK (e’) positive cells in the graft core. (f) Composite overlay of graft-derived neurons and glial cells migrated into

the host territories. (g) Representative images of DCX-positive human neurons migrated out of the graft core, displaying either migratory (g) or more differentiated

(g’) morphologies. (h-i) Representative images of human SOX9-positive astrocytes (h) and SOX10-positive oligodendrocytes (i) outside the graft core. (j) Longitudinal

quantification of the fraction of grafted cells expressing CTIP2, GABA or SOX9 at 2 and 6MPT. Scale bars, 50 µm (d-e’, g-i). 2MPT: N = 6 rats; 6MPT: N = 6–7 rats.

Data presented as mean ± sem. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ****p < 0.0001. See the statistics table for details (Suppl. Table 5).

Overall, these findings suggest that graft-derived projections undergo a process of refinement which may still be ongoing at 6MPT. These results further demonstrate that hSP-grafts establish reciprocal connectivity with the host brain, receiving inputs from, and projecting to, appropriate brain regions of both the direct and the indirect pathway. Altogether, these findings support the capacity of hSP-derived neurons to integrate into existing circuitry and contribute to striatal circuit reconstruction.

¶ 3.4. Graft-derived neurons exhibit functional integration as evidenced by spontaneous and evoked activity

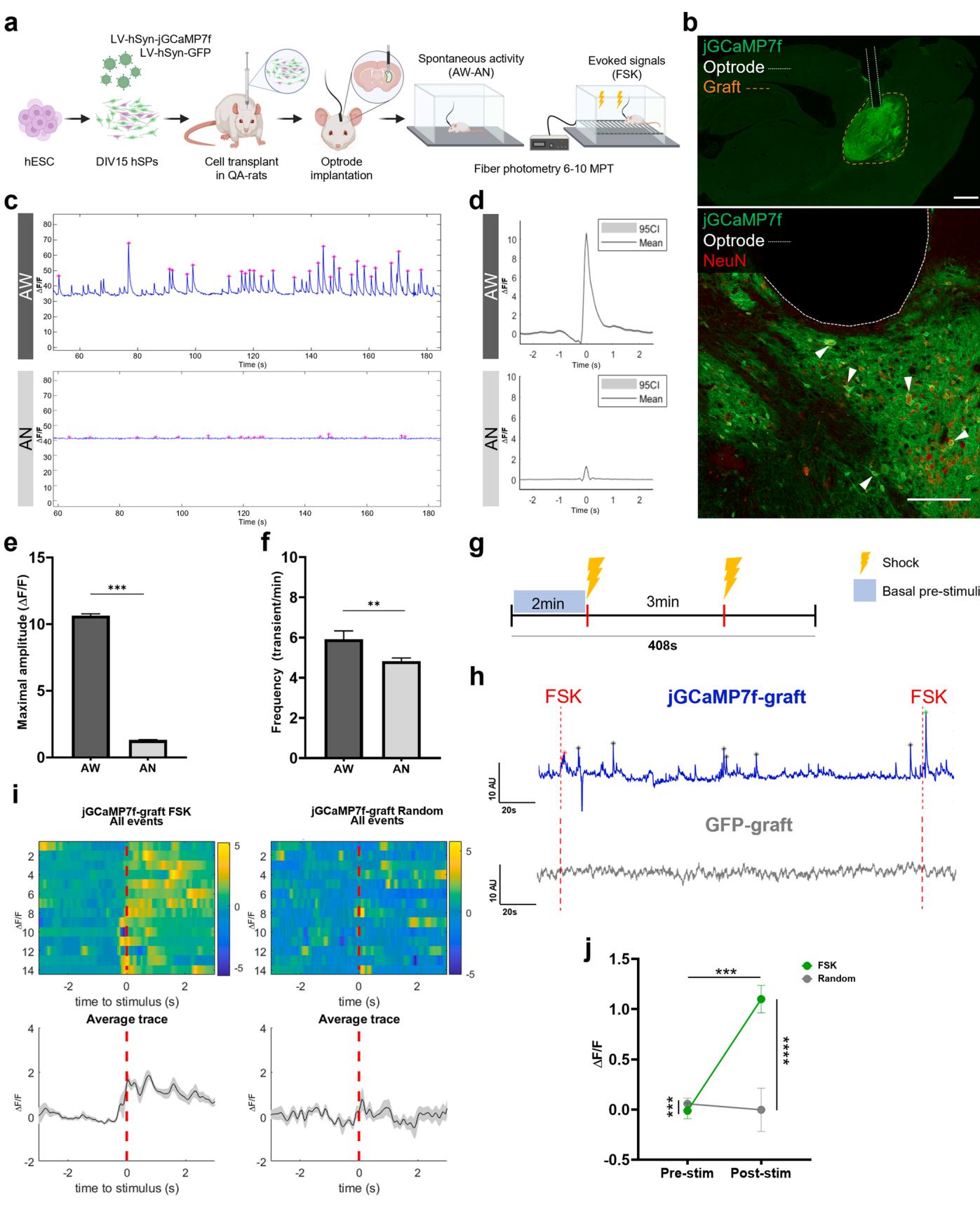

The investigation of graft afferents and projections highlighted the integration of hSP-grafts in the host tissue. To assess the actual functionality of the grafted cells, we employed a genetically-encoded calcium sensor (jGCaMP7f) to monitor graft signaling in living animals.

To this aim, we used fiber-photometry to record calcium signals in freely moving (awake, AW) and anesthetized (AN) conditions (Fig. 4a). Well-defined signals were observed in three rats transplanted with hSPgrafts expressing jGCaMP7f and in one animal transplanted with hSPgraft expressing GFP (Fig. S5a, b). In these animals, histological inspection confirmed the presence of grafted neurons in the recorded region and proper optrode implantation, either directly above the graft or within the effective detection range of approximately [18] (Fig. 4b; Fig. S5c). As an additional negative control, we also included one animal in which the graft did not survive, to reveal graft- and calcium-independent artifacts (No-graft, Fig. S5b).

In two of the three jGCaMP7f-grafted rats, sustained oscillatory activity was observed in most recordings (Fig. 4c). The peaks represented evident calcium transients with the expected average shape (fast rise followed by a slow decay; Fig. 4d). Conversely, spontaneous activity in the GFP-grafted and No-graft animals was characterized by peaks displaying a sharp and symmetrical shape, with fast decay, which do not reflect calcium dynamics and indicate substantial noise (Fig. S5b). jGCaMP7f-graft recorded calcium transients showed variable amplitudes, with a maximal mean amplitude of (AU), occurring at an average frequency of per minute. This activity persisted for over four months (from 6MPT to 10MPT) and was significantly reduced under AN to a maximal mean amplitude of , and an average frequency of (Fig. 4d-f). The third rat recipient of a jGCaMP7f-graft exhibited only sporadic calcium activity, detected in of the recordings (Fig. S5d). This activity displayed intermittent trains of low-amplitude peaks (maximal amplitude, , representing about of the average amplitude observed in the other two rats. Under AN, the amplitude further decreased to , while the average frequency remained unchanged (AW, ; AN, 3.53 $\pm \ : 0 . 3 5 $ . Fig. S5d). Spontaneous activity traces in the rat with the GFPgraft showed oscillations with mean peak amplitudes and average frequencies markedly lower than those observed in animals with jGCaMP7f-grafts (Fig. S5e), and similar to those recorded in the No-graft control rat (Fig. S5b, e). Notably, AN significantly reduced amplitude values in both the GFP-grafted rat (AW, ; AN, and the No-graft rat (AW, ; AN, , suggesting movement-related contributions (AW condition) to these signals (Fig. S5e). Further, AN had no effect on the frequency in the GFP-graft (AW, ; AN, , while it was associated with a paradoxical signal increase in the No-graft rat (Fig. S5e). Overall, these results indicate that hSP-grafts exhibit spontaneous activity.

However, the presence of spontaneous calcium activity does not necessarily imply functionally connectivity with the host brain regions, as peaks may result from neural activity intrinsic to the graft itself. To assess whether the graft received functional inputs, we delivered foot shocks (FSK) to the transplanted animals (Fig. 4g). This stimulus is known to elicit calcium responses in the striatum [35], suggesting that the grafts could respond if functionally connected. Indeed, FSK induced specific calcium responses in two of the three rats with jGCaMP7f-grafts, but not in the rat with the GFP-graft (Fig. 4h), as shown by a stronger evoked response (post- vs. pre-stimulus) in the stimulus-locked compared to the random-locked condition (FSK vs. random, Fig. 4i-j). Notably, no response was detected in the jGCaMP7f-grafted rat with sporadic calcium activity (Fig. S5f), suggesting insufficient connectivity in this animal. Moreover, such FSK-evoked responses were absent in the animal recipient of the GFP-graft, and in the No-graft control, which even showed a slight post-stimulus signal decrease (Fig. S5f). These results suggest that hSP-grafts establish behaviorally relevant connections with the host circuitry.

In conclusion, spontaneous activity demonstrates that neurons in hSP-grafts attain functional maturity, while evoked responses confirm their integration into the host neuronal network including circuits involved in processing sensory stimuli. These findings confirm that neurons derived from hSP-grafts can participate in the signaling processes characteristic of mature circuits, thereby contributing to the overall functionality, adaptability and potential recovery of the host’s damaged neuronal network.

¶ 3.5. Chemogenetic modulation reveals functional integration and behavioral impact of hSP-grafts

To further verify the functional integration of hSP-grafts into host neural circuits, we leveraged a chemogenetic tool for both ex vivo and in vivo experiments (Fig. 5a). To this end, we generated a stable clonal hESC line expressing bidirectional DREADD receptors (Bi-DREADD), as previously described [36] (Fig. S6a-c), and validated the best clone following striatal differentiation. At DIV35, the cells expressed typical MSNs markers alongside strong expression of both mCherry-tagged hM3Dq and HA-tagged KORD receptors (Fig. 5b, c). The functionality of the system was assessed by time-lapse calcium imaging using the calcium indicator Fluo4 under basal conditions and after the addition of the hM3Dq-specific ligand CNO or the KORD-specific ligand SALB, with DMSO as a vehicle control. Specifically, CNO administration significantly increased the number of activated ROIs and network connectivity, while SALB reduced them, relative to vehicle, confirming the bidirectional chemogenetic modulation of neuronal activity (Fig. 5d, e;

Fig. 3. Analysis of graft inputs and axonal projections. a).Schematic illustration of the experimental workflow for analysis of monosynaptic inputs and axonal projections. b) Quantification of traced cells and localization in the different cortical layers and thalamic nuclei at 2MPT. b’) High magnification confocal image showing primary afferent inputs (GFP-negative/mCherry-positive) to grafted cells in the primary motor cortex and thalamus at 2 and 6MPT. c)Three-dimensional rendering of mCherry-positive cell distribution and anatomical localization in atlas-referenced brain regions from a cleared brain imaged with light-sheet microscopy. d)Histogram depicting the graft and the host brain regions reached by hNCAM-positive graft-derived axons. Quantification of Proportions of hNCAM-positive fractionated area within graft-innervated regions at 2 and 6MPT are quantified in . e) Representative images showing hNCAM-positive graft-derived fibers projecting to the GP and SN at 2 and 6 MPT. Scale bars, (b) and (e). 2MPT: rats; 6MPT: rats. Data presented as mean . , , . See the statistics table for details (Suppl. Table 5).

Fig. 4. In vivo spontaneous and evoked calcium signals in jGCaMP-grafts. Experimental design for the in vivo fiber-photometry recordings of hSP-grafts. (a) Representative brain section, showing the optrode trajectory and end-tip (white dotted line) in contact with the jGCaMP7f-graft (orange dotted line) expressing NeuN. (b) Representative traces of recordings from jGCaMP7f-grafts under AW and AN; detected peaks are denoted by the pink asterisks ., ©. Average shape of jGCaMP7f-graft transients, aligned to the maximal amplitude in AW (slope decay , peaks) and AN (slope decay~0.25 s, peaks). e) Maximal amplitude of the jGCaMP7f-graft transients in AW and AN (AW, ; AN, detected peaks). f) Frequency of the jGCaMP7f-graft transients in AW and AN (AW, ; AN, recordings). g) Experimental design of the applied FSK protocol. h) Representative traces of recordings from jGCaMP7f- and GFP-grafts during the FSK test. Only jGCaMP7f-grafts showed spontaneous signals and responses (indicated by asterisks, ) evoked by the FSK. i) FSK-evoked responses in jGCaMP7f-grafts. Upper panel: heatmap illustrating the signals per trial aligned to the time of the FSK or to a Random time. Lower panel: average signals and confidence interval (CI, grey shadow) of the detected activity. j) jGCaMP7f-grafts evoked responses in each type of alignment (FSK vs. Random) recorded pre- and post-stimuli (stim). trials. Overall signals are different (interaction , group factor ). Signals post- vs. pre-stim are significantly different (condition factor ), increasing only after the FSK (FSK ; Random ns). trial Scale bar, (b), (b inset). Data presented as mean . , ns . See the statistics table for details (Suppl. Table 5).

S6f-h; Suppl.Video 2–4). Following in vitro validation, hSPs carrying the Bi-DREADD system were transplanted into QA lesioned rats. At 6MPT, immunofluorescence confirmed persistent expression of the Bi-DREADD system and consistent differentiation into MSNs within the graft (Fig. 5f).

At the same time point, we performed ex vivo multielectrode array (MEA) recordings from sagittal brain slices obtained from transplanted animals, positioned so that the graft overlapped with the electrode array (Fig. S7c). Bath application of dopamine (DA) led to a significant increase in the mean firing rate, burst number, and current amplitude, indicating dopaminergic responsiveness of grafted neurons (Fig. . Similarly, the application of CNO enhanced these parameters, while SALB reduced spiking activity, confirming successful chemogenetic activation and inhibition of the graft, respectively (Fig. 55g-m). Moreover, both DA and CNO produced a qualitative increase of neural network cross-correlation relative to baseline, consistent with mature network activity within the graft (Fig. S7b). Importantly, the administration of the same ligands had no detectable effect in regions outside the graft (Fig. S7a), indicating that dopamineevoked responses originated from the transplanted cells, rather than from resident host neurons surrounding the graft. Collectively, these findings confirm the successful long-term engraftment of hSP-grafts, capable of differentiating and integrating into host circuits and acquiring functional dopaminergic responses.

In the context of cell replacement therapy for HD, direct evidence of graft integration into host circuitry and modulation of motor behavior remains scarce. To address this, hSPs carrying the Bi-DREADD system were transplanted into QA-lesioned rats and used to modulate motor behavior through targeted chemogenetic stimulation at 8MPT (Fig. 6a). The administration of either CNO or SALB significantly reduced average velocity in the open field in grafted animals, while lesioned-only controls showed no response to ligand, confirming functional graft integration and the ability of graft activity to modulate voluntary motor behavior (Fig. 6b, c).

Additionally, analysis of grooming behavior - particularly relevant for striatum-mediated fine motor control [15] revealed that SALB administration significantly increased the number of incomplete or incorrect grooming sequences, consistent with a disruption of fine motor coordination following graft silencing. Conversely, CNO increased the number of correct grooming sequences, although this effect did not reach statistical significance, supporting the notion that chemogenetic activation of grafted neurons enhanced striatal coordination of fine motor behavior (Fig. 6d).

To summarise, chemogenetic activation or inhibition of the graft modulated neuronal activity in vivo, confirmed by changes in firing rates and network connectivity. Importantly, in vivo modulation of graft activity at 8 MPT significantly influenced motor behavior as both activation and silencing altered open field velocity, and silencing disrupted fine motor control as evidenced by increase in impaired grooming sequences. Baseline performance comparison did not reach statistical significance.

Collectively, these findings demonstrate that hSP-grafts not only establish functional connectivity with the host striatal circuitry but also modulate striatum-dependent behaviors.

¶ 4. Discussion

This study provides in vivo evidence that hESC-derived hSPs can survive, differentiate, integrate into host circuits, and modulate behavior following transplantation in the QA rat model of HD. Using a comprehensive and diversified set of approaches - including singlenucleus transcriptomics, spatial mapping, immunohistochemistry, in vivo calcium signal recordings, electrophysiology, and chemogenetic manipulations, we show that hSP-grafts recapitulate key features of ventral telencephalic development. These include the generation of striatal projection neurons, interneurons and astrocytes, which are able to modulate striatal-related behaviors.

To our knowledge, this is the first study to perform snRNAseq of hSPgrafts after transplantation in the QA model of HD and matched cells undergoing neuronal differentiation in vitro. Compared to a previous study where about 200 cells from neural stem cells-derived grafts were transcriptionally profiled [37], we were able to scale up to over 17,000 and 10,000 cells from grafts and in vitro cultures, respectively. This approach provides an unprecedented level of resolution for characterizing the cellular composition and organization of the graft in vivo, overcoming the limitations of traditional histological approaches. Moreover, comparison between in vivo grafts and in vitro differentiated cells provided additional insights by underscoring the relevance of environmental interactions for long-term differentiation. Importantly, snRNA-seq enabled the identification of both canonical and non-canonical striatal subtypes, revealed spatial patterning, and captured transcriptional features associated with neuronal maturation, gliogenesis, and lineage plasticity. These insights are critical for evaluating graft fidelity and for guiding the refinement of differentiation protocols aimed at achieving precise cell type specification for therapeutic applications.

In particular, we show that grafts were composed of transcriptionally diverse cell types including both D1- and D2-type MSNs, MGE and CGEderived interneurons, and astrocytes with telencephalic identities. Notably, the comparison of transcriptional profiles of the grafted cells with those from publicly available mouse and human adult datasets confirmed proper regionalization and maturation patterns along ventral telencephalic trajectories. Furthermore, cross-validation with orthogonal datasets reinforced the cell annotation accuracy, offering integrated transcriptional and spatial evidence confirming the authenticity of hSP-grafts striatal identity. The observed cellular heterogeneity likely reflects the intrinsic plasticity of early ventral forebrain progenitors during in vitro patterning, particularly within overlapping temporal windows of LGE and MGE fate specification. In line with previous studies, early-stage ventral forebrain progenitors exposed to SHH and other ventralizing signals may give rise to both LGE- and MGE-derived subtypes, depending on the timing and concentration of morphogen exposure [38]. Although the in vitro protocol was primarily neurogenic, a gliogenic switch emerged in vivo, as indicated by the progressive appearance of astrocytes from 2 to 6MPT, likely reflecting the endogenous neurogenic-to-gliogenic switch that occurs around 15 gestational

Fig. 5. Functional validation of Bi-DREADD hESCs differentiated into hSPs and grafted in QA-lesioned rats. (a) Experimental workflow for hSP-graft chemogenetic bidirectional manipulation. (b) Immunostaining shows co-expression of hM3Dq-mCherry and HA-tagged KORD in hSPs on DIV35 from Bi-DREADD hESCs. © Immunostaining shows the expression of typical MSN markers CTIP2 and GABA in hSPs on DIV35 from Bi-DREADD hESCs. (d)Bar graph showing the percentage of spiking ROIs within a 24-second interval of Fluo-4 calcium transients following the addition of specific ligands (DMSO, CNO, SALB) at least 6 different wells deriving from two independent biological replicates).(e) Graphical representation showing the functional connectivity between ROIs, derived from their synchronous activity in 180-second window of Fluo-4 calcium transients following the application of specific ligands (DMSO, CNO, SALB). least 6 different wells deriving from two independent biological replicates). (f) Immunohistochemistry images show that striatally grafted hSPs from Bi-DREADD hESCs co-expressed hDARPP32 and hM3Dq-mCherry. (g) Raster plot illustrating the temporal pattern of neuronal spiking activity recorded across multiple electrodes during MEA recording. Each row represents a single electrode, and each horizontal tick marks the timing of an individual spike. For each condition , CNO, SALB), 30 s of activity are reported. (BASAL, DA, CNO: slices from 3 animals; SALB: slice). (h-o) Bar graph showing different MEA parameters measured on graft region during recording for each condition (BASAL, DA, CNO): h) Percentage of active spike units, i) Mean firing rate (spikes/second), Current amplitude (pA), k) Spike events, l) Burst events, m) Burst frequency (bursts/s). (BASAL, DA, CNO: slices from 3 animals). Scale bars, (a, c, e, inset f). Data presented as mean . , , . See the statistics table for details (Suppl. Table 5).