¶ A high‑density multi‑electrode platform examining the efects of radiation on in vitro cortical networks

Megan Boucher‑Routhier1 , Janos Szanto2 , Vimoj Nair2 & Jean‑Philippe Thivierge1,3*

Radiation therapy and stereotactic radiosurgery are common treatments for brain malignancies. However, the impact of radiation on underlying neuronal circuits is poorly understood. In the prefrontal cortex (PFC), neurons communicate via action potentials that control cognitive processes, thus it is important to understand the impact of radiation on these circuits. Here we present a novel protocol to investigate the efect of radiation on the activity and survival of PFC networks in vitro. Escalating doses of radiation were applied to PFC slices using a robotic radiosurgery platform at a standard dose rate of 10 Gy/min. High-density multielectrode array recordings of radiated slices were collected to capture extracellular activity across 4,096 channels. Radiated slices showed an increase in fring rate, functional connectivity, and complexity. Graph-theoretic measures of functional connectivity were altered following radiation. These results were compared to pharmacologically induced epileptic slices where neural complexity was markedly elevated, and functional connections were strong but remained spatially focused. Finally, propidium iodide staining revealed a dose dependent efect of radiation on apoptosis. These fndings provide a novel assay to investigate the impacts of clinically relevant doses of radiation on brain circuits and highlight the acute efects of escalating radiation doses on PFC neurons.

Keywords Radiation, Multielectrode array, Prefrontal cortex, Complexity, Functional connectivity, Neuronal activity

Radiation therapy and stereotactic radiosurgery are increasingly used to treat conditions such as primary and metastatic brain tumors, trigeminal neuralgia and intractable epilepsy1, 2 . Despite their widespread use, the efects of radiation on surviving neuronal networks remain poorly understood2 . Radiation can produce brain injuries that occur on diferent timescales following treatment. Acute radiation-induced injuries typically occur within days of radiation, whereas early delayed injuries occur within one to six months post-radiation, and late delayed injuries occur over 6 months post-radiation3, 4 . Radiation-induced brain injuries have been associated with several cognitive impairments such as memory, attention, and executive function defcits, as well as reduced processing speed, which can occasionally progress to dementia3, 4, 5 . Tese injuries appear to be dose-dependent, whereby patients who receive higher doses tend to have worse long-term outcomes5 .

Radiation-induced brain injuries are thought to be caused by a combination of cell death and dysfunction in surviving brain cells. Previous literature examining acute and early delayed efects of radiation has established that irradiated neurons show signifcantly increased fring rates2, 6 , changes in synaptic morphology2, 7 , and inhibited synaptic function and plasticity including defcits in long-term potentiation4, 8 . Larger doses of radiation in the primary visual cortex of Göttingen minipigs have also shown signifcant decreases in fring rate 6-months post-radiation suggesting distinct efects in acute compared to late delayed radiation-induced brain injuries6 .

Past research has primarily focused on the impact of radiation on the hippocampus due to its association with memory impairments. However, more recent work has highlighted the importance of studying other brain regions such as the prefrontal cortex (PFC). Te PFC is a key region of interest because it is responsible for several important functions including executive function, decision-making, and working memory9 . Neurons located within the PFC communicate with one another and with adjacent sensory, motor, and subcortical regions through precisely-timed action potentials that are impacted by radiation therapy4, 10. Further, the PFC has close functional connections with the hippocampus through a direct monosynaptic pathway that originates in the cornu ammonis 1 (CA1)/subiculum felds of the hippocampus and projects to the prelimbic and medial orbital areas of the PFC4, 11. Tus, the PFC is a major contributor to inter-regional hippocampal communication and a region of central importance in understanding cognitive impairments following radiation2, 12.

Large-scale, high-density multi-electrode arrays (hd-MEAs) are gaining widespread interest as a tool to monitor brain networks in vitro13. Because of their ability to record from broad networks at high spatial and temporal resolution, hd-MEAs ofer a middle ground between single-cell recordings and very large-scale neural activity obtained with electrocorticograms or electroencephalograms. State-of-the-art hd-MEAs can monitor thousands of neurons simultaneously at sufcient temporal resolution to isolate individual action potentials, providing a rich insight into patterns of network activity during both healthy and altered cortical states14.

In this work, a novel assay was developed where hd-MEAs were employed to monitor the neuronal activity of in vitro PFC slices following radiation, with a focus on acute radiation-induced dysfunction. To the best of our knowledge, this is the frst time that any MEA technology has been used to study the impacts of therapeutic doses of radiation on in vitro PFC circuits. Various markers were designed to quantify changes in network dynamics and apoptosis, including population fring rates, functional connectivity, graph-theoretic measures, and neural complexity. Comparisons of these markers between radiation and pharmacologically induced epileptiform activity revealed a distinct signature of radiation-induced changes in network function. Tese results suggest that hd-MEAs constitute a novel and viable assay to investigate the impact of clinically relevant doses of radiation15, 16 on neuronal dysfunction and apoptosis.

¶ Results Irradiated brain slices reveal changes in cortical population activity

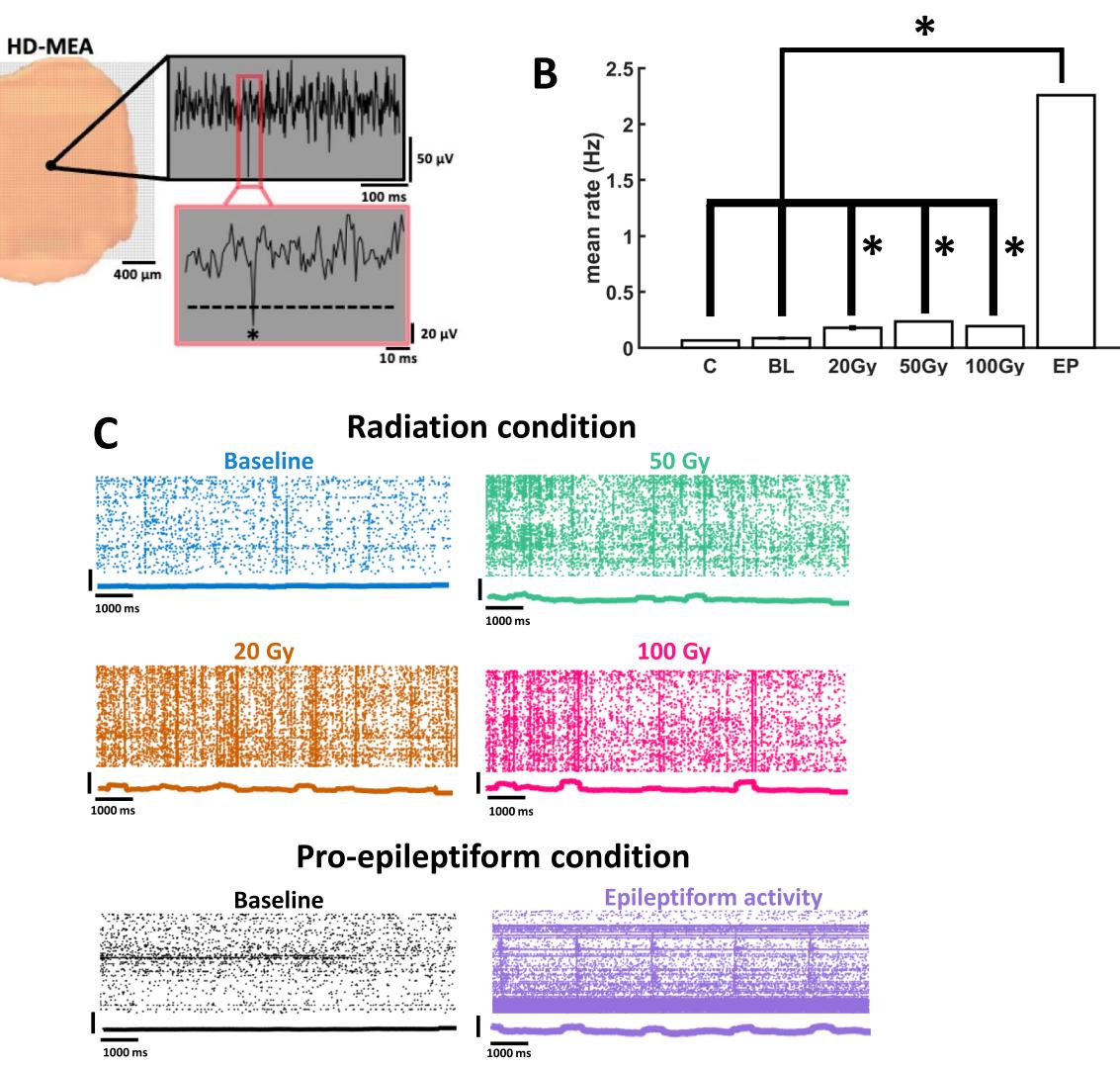

Neuronal activity recorded on the hd-MEA was characterized by sharp defections in voltage at individual channels, indicative of multi-unit spikes amongst clusters of neurons in the vicinity of the electrodes (Fig. 1A). Tese defections were detected by application of a threshold below the mean of the voltage (see “Methods”). Te rate of neural activity at individual channels was computed as the average number of a pronounced increase in fring rate was observed following PE treatment (mean rate of compared to a baseline fring rate of , . Further work characterizing epileptiform activity in terms of propagating waves can be found elsewhere17. Tese results show that radiation-induced changes in neuronal activity remained markedly lower than epileptiform activity.

Treshold-crossing events per second and stored as rasters for ofine analysis. Tese rasters revealed an increase in activity among radiated slices compared to controls (Fig. 1B). A dose of 20 Gy radiation yielded a statistically reliable increase in mean fring rate compared to sham radiation (Wilcoxon rank sum test, ), as did and 100 Gy ). Examples of individual rasters are shown in Fig. 1C, where individual dots identify the times and channels where these events occurred.

¶ Probing alterations in functional connectivity

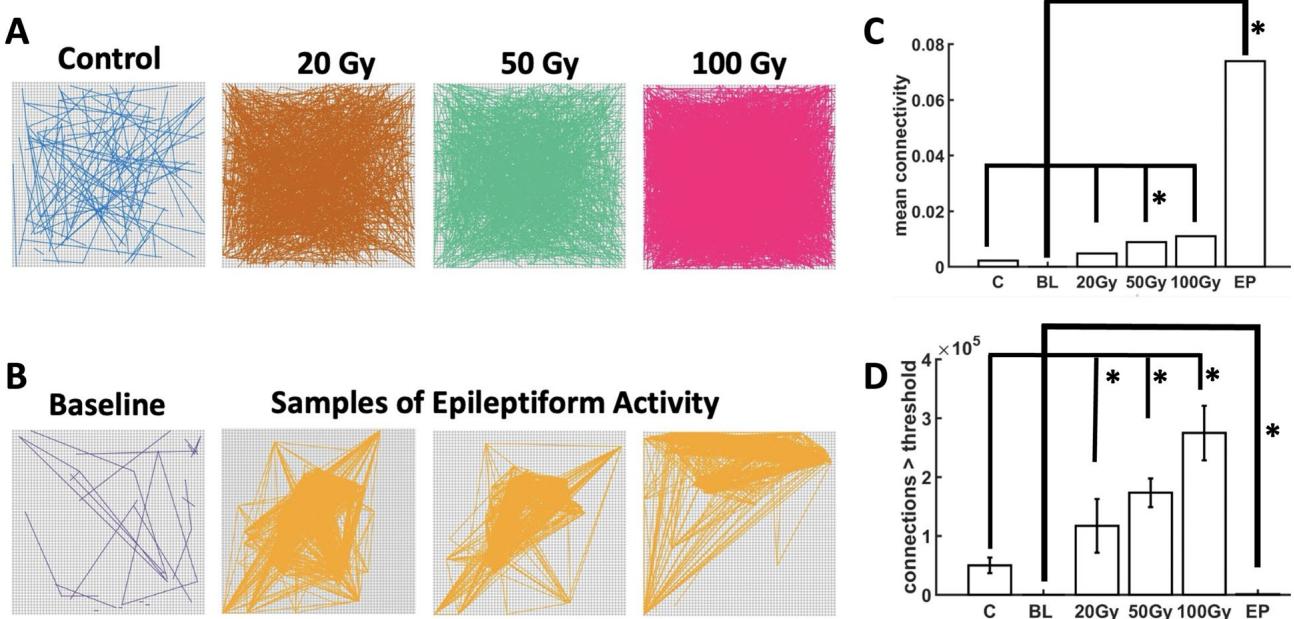

Next, we examined functional connectivity amongst cortical neurons by computing correlations between all pairs of channels on the hd-MEA (Fig. 2A, B). Functional connectivity is indicative of the communication amongst populations of neurons and is known to fuctuate in disease states18, 19, 20, 21. To facilitate the interpretation of functional networks, a cut-of of was applied to reject lower correlations amongst pairs of channels.

Two markers of functional connectivity were examined, namely the strength and the number of functional connections across conditions. Te strength of functional connectivity following radiation was higher than controls across all doses of radiation delivered to the PFC slices (Fig. 2C). Functional connections were signifcantly stronger than controls for 50 Gy but did not reach statistical signifcance for 20 Gy or 100 Gy . Despite variability across conditions, the overall impact of radiation was an increase in the strength of functional connections across PFC networks, indicative of greater synchronization amongst neurons.

In radiated slices, the number of functional connections showed a dose-dependent response, with higher doses yielding more abundant connections than lower doses (Fig. 2D). Te number of functional connections was higher than controls for 20 Gy ), 50 Gy ) and 100 Gy ). Tus, radiation impacted PFC functional connectivity by increasing the density of connections amongst pairs of channels on the array.

Tese results were compared to networks that received PE treatment (Fig. 2B). Te mean strength of functional connectivity was markedly higher in PE compared to radiated slices (20 Gy: ; 50 Gy: ; 100 Gy: ), suggesting an increase in synchrony during PE activity. Conversely, the number of functional connections was lower in PE compared to radiated slices (20 Gy: ; : ; 100 Gy: ). Te lower number of connections obtained under PE treatment is explained by epileptiform activity yielding functional interactions that are focused on a small group of neurons within the broader population recorded on the array (Fig. 2B). Indeed, seizure-like events observed under PE are characterized by a spatially-focused propagation of strong and repeatable patterns of activity17. In sum, radiation induced more abundant functional connections amongst PFC neurons. Tese results are distinct from epileptiform activity, where strong connections are present but are much sparser due to spatially focused epileptiform propagation across the array.

Fig. 1. Neuronal activity in populations of prefrontal cortical neurons. (A) Lef, example of PFC slice placement on the hd-MEA. Right, multiunit spike (identifed by an asterisk ) extracted from voltage defections identifed at an individual channel. (B) Mean fring rate of prefrontal cortical neurons across various conditions. control slices for the radiation treatment; baseline in the PE condition; radiation conditions; epileptiform activity. *indicates statistical signifcance at . © Rasters of activity show spikes across whole populations of neurons following graded doses of radiation or perfusion of pro-epileptiform solution. Peri-stimulus time histogram underneath each raster shows summated activity using a rolling window.

¶ Graph‑theoretic measures of functional networks

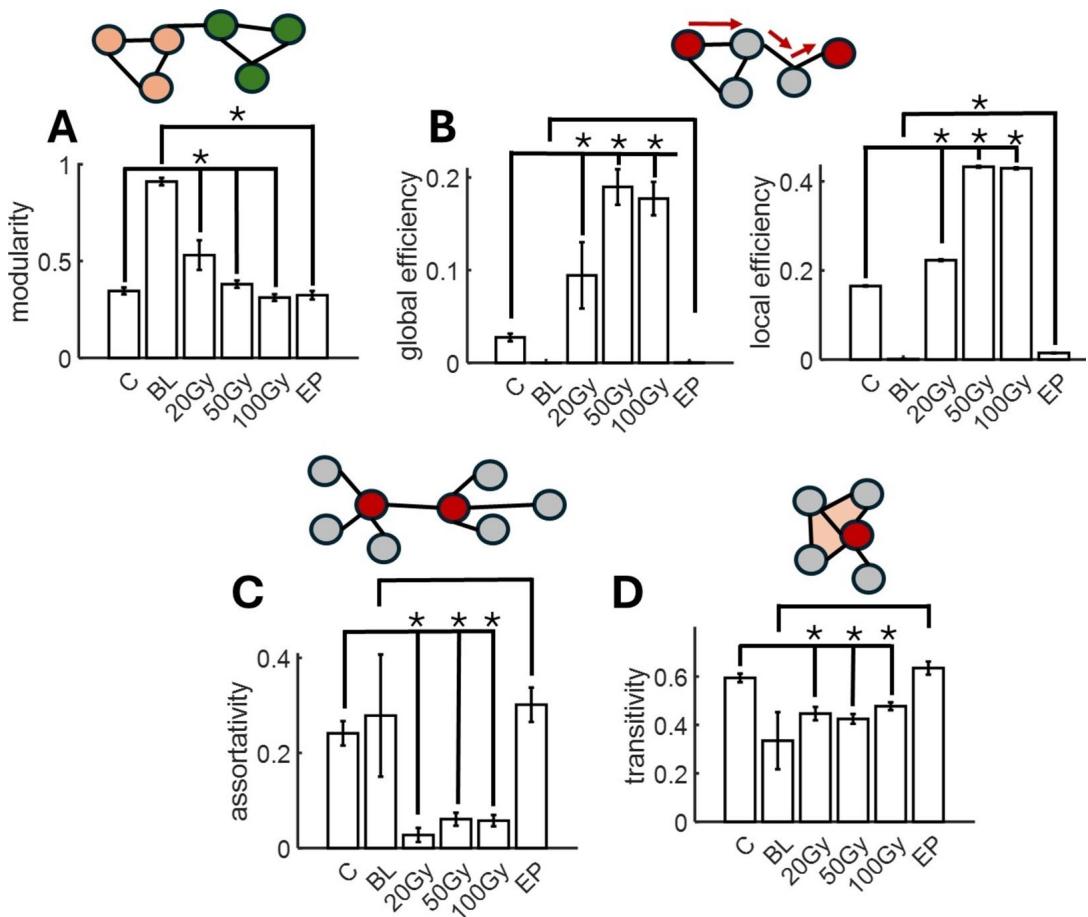

Functional networks were further characterized by examining fve graph-theoretic metrics, namely modularity, global efciency, local efciency, assortativity, and transitivity22. Te modularity of a network refects the extent to which nodes may be divided into non-overlapping modules, where nodes within a module share a high number of connections. Relative to baseline networks, epileptiform (EP) networks attained lower modularity ) (Fig. 3A). A lower dose of radiation yielded a moderate increase in modularity relative to controls , but no efect was found at higher doses and ). Hence, epileptiform activity decreased the modularity of functional networks, but no reliable alteration was found across radiated networks.

Te global efciency of functional networks computes the average of inverse shortest paths between nodes. Networks where only a few connections need to be traversed between pairs of nodes have a high global efciency. We found high global efciency in functional networks following radiation (20 Gy: ; 50 Gy: ; 100 Gy: (Fig. 3B). Tis efect was not replicated in EP networks, where global efciency remained low. We reasoned that this result may be due to EP networks occupying a delimited region on the array (Fig. 2B). To control for this efect, we computed local efciency, which measures the connections around individual connected nodes. Local efciency yielded a signifcant increase in EP networks relative to baseline , consistent with the idea that EP increases local efciency around. Individual nodes participating in epileptiform activity (Fig. 3B). Local efciency was also increased in radiated networks : ; 50 Gy: \pmb { \mathstrut } p = 4 . 1 5 4 8 \mathsf e { - } 1 2 ; 100 Gy: .

Fig. 2. Functional connectivity of cortical networks. Radiation (A). Perfusion of a pro-epileptiform (PE) solution (B). Mean strength © and number of functional connections exceeding a pre-defned threshold (D Asterisks indicate signifcance at (Wilcoxon rank sum test).

Fig. 3. Graph-theoretic properties of functional connectivity. Modularity (A), global and local efciency (B), assortativity ©, and transitivity (D) were computed across experimental conditions. A cartoon illustration of each measure is shown above fgures.

Network assortativity determines the extent to which pairs of nodes that are connected together have a similar number of connections (technically termed the degree of a node) to other nodes in the network. As an illustration, Fig. 3C shows two nodes that have the same number of connections, and hence high assortativity. We found a decrease in assortativity in radiated networks (20 Gy: ; 50 Gy: ; 100 Gy: ), but no reliable change for EP networks.

Te transitivity of a network measures the extent to which pairs of nodes that are connected together also share a common neighbor. Visually, functional networks with high transitivity show closed triangles between triples of nodes (Fig. 3D). We found a moderate decrease in transitivity for radiated slices relative to controls : ; 50 Gy: ; 100 Gy: ). No such efect was reported for EP networks.

Taken together, graph-theoretic measures of functional networks revealed diferent classes of metrics, where some metrics are preferentially altered in radiated networks (global efciency, assortativity, and transitivity), while others are altered more specifcally in EP networks (modularity) or for both radiation and EP (local efciency). Tese measures of functional connectivity open a potentially rich feld of investigation into network-level alterations under a variety of neuronal states and conditions.

¶ Global synchronization

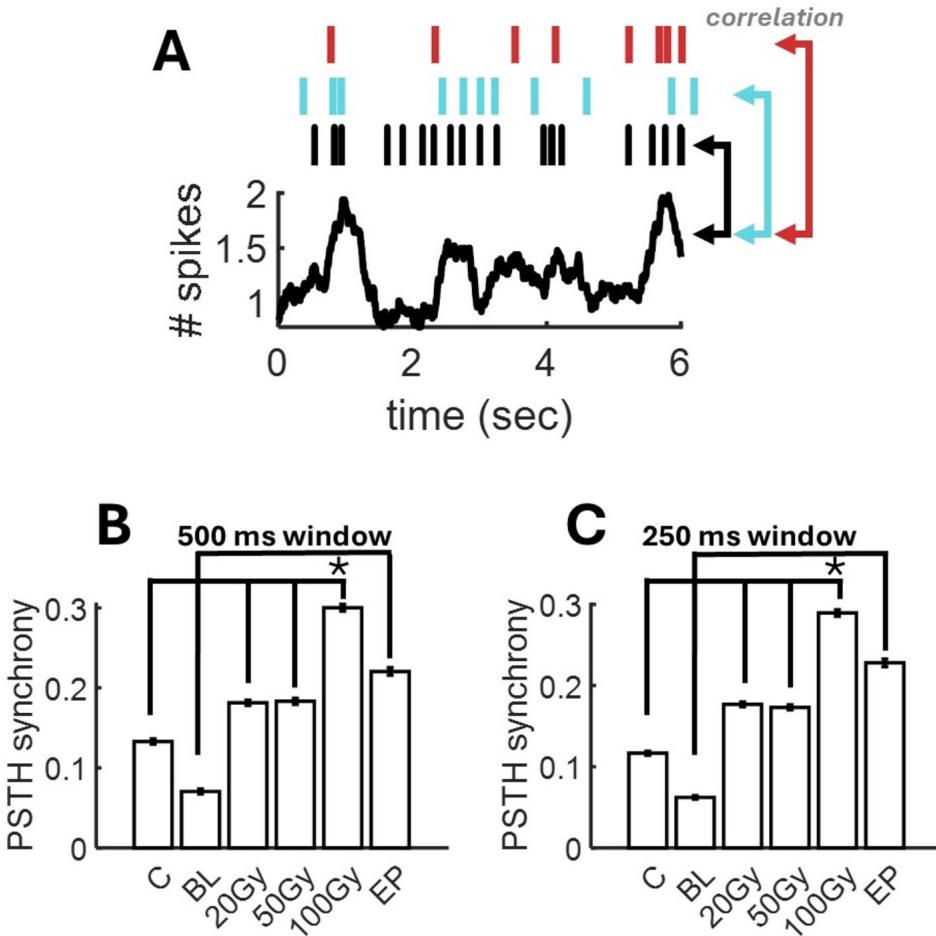

To examine alterations in synchronization induced by radiation and PE, we began by temporally averaging spike rasters using a rolling window, then computed the peri-stimulus time histogram (PSTH) by summing activity across channels. Next, we calculated the correlation between spikes at individual channels and the PSTH (Fig. 4A). A high correlation is indicative of global synchronization between each neuron and fuctuations in population activity. Overall, high radiation signifcantly increased synchronization (Fig. 4B) ), but not lower doses (20 Gy: $ { p } { = } 0 . 2 2 8 1 8$ ; 50 Gy: ). Global synchronization increased only marginally in EP networks , for two probable reasons. First, periods of epileptiform activity are interspersed by intervals of quiescent activity with no marked synchrony17. Second, epileptiform activity remained spatially delimited (Fig. 2B), thus limiting global synchronization. Comparable results were obtained when lowering the rolling window to (Fig. 4C). Tus, an increase in global synchronization was obtained with high radiation doses and did not emerge from lower radiation doses or epileptiform activity.

Fig. 4. Alterations in global synchronization. (A) Synchronization is computed by the correlation between spikes at individual channels (top) and the PSTH obtained by summing all neurons in the population afer averaging with a rolling temporal window. (B-C) Mean synchronization across conditions using a rolling window of or .

¶ Dynamical complexity of population activity

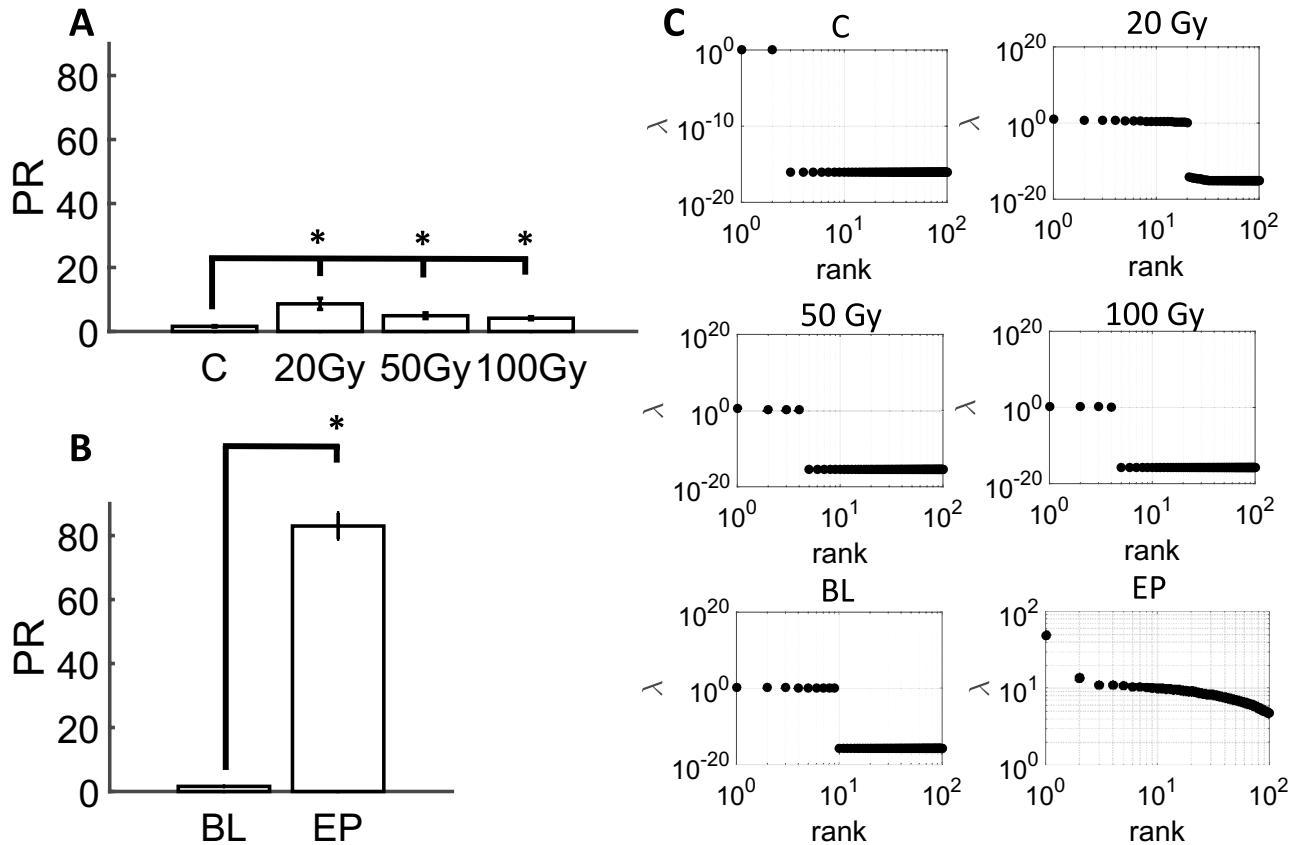

Te complexity of population activity was examined in both radiated and PE slices, indicative of the number of factors required to capture the neuronal data23, 24, 25, 26. Te complexity of radiated slices was higher than controls across all doses of radiation delivered to PFC (Fig. 5A). Complexity was signifcantly higher than controls for ), 50 Gy ), and . Tus, radiation reliably increased the complexity of neural data recorded on the hd-MEA

Tis result was compared to the efect of PE treatment. Relative to baseline activity, slices treated with PE yielded a marked increase in complexity (Fig. 5B). Te magnitude of this efect exceeded the complexity of radiated slices, suggesting that while radiation increased the complexity of neural activity, this efect was limited compared to the high complexity obtained from epileptiform activity, thus showing that population activity following radiation is distinct from a regime of PE-induced seizures. Eigenvalue distributions across experimental conditions further supported this point. In controls and radiated slices, a limited number of eigenvalues yielded positive values; by comparison, PE activity was characterized by a broad distribution of eigenvalues spanning at least two orders of magnitude (Fig. 5C).

Together, the above results on fring rates, functional connectivity, and complexity show clear distinctions between epileptiform and radiation-induced changes in neuronal activity across populations of cortical cells. While both forms of activity were characterized by an increase in fring rates, radiated slices exhibited diferent patterns of functional connectivity and lower complexity than PE-treated slices.

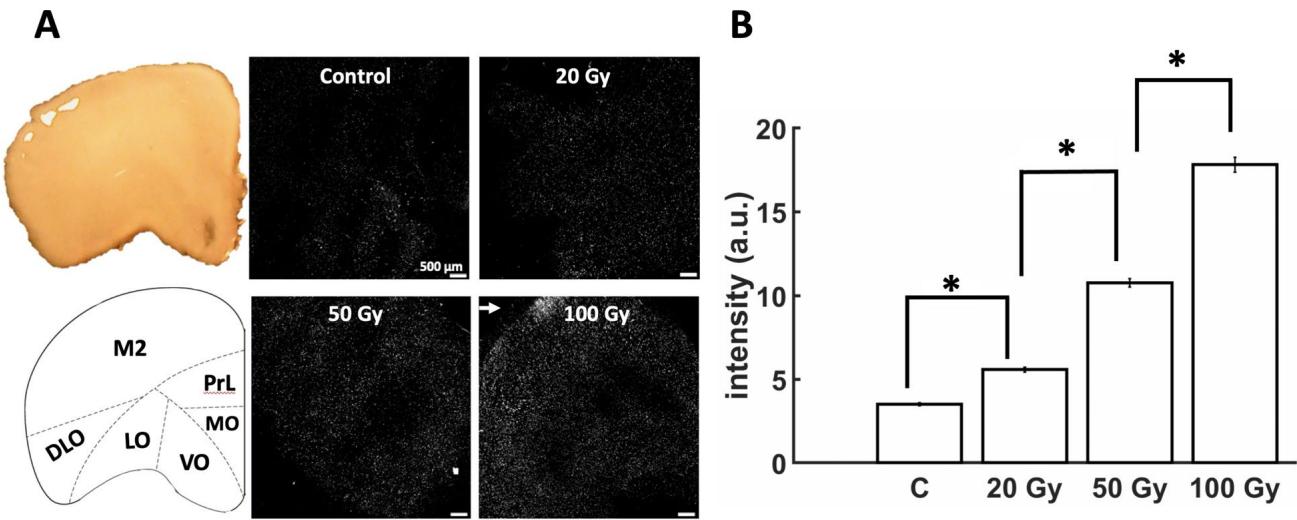

¶ Quantifying cell death following radiation

A subset of slices was stained with PI following radiation or sham radiation (control) conditions (Fig. 6A). Te mean pixel intensity across radiation conditions revealed a trend whereby higher doses resulted in a higher level of cell death (Fig. 6B). In this way, yielded higher intensity than controls ), 50 Gy was above ( , and 100 Gy above ). Tus, cell death was linked to the radiation dose delivered to PFC neurons. At higher doses, particularly we observed a clustered spatial arrangement of pixels with higher intensity, suggesting an area where cellular damage was more pronounced (Fig. 6A, arrow). Interestingly, this area is in the vicinity of the secondary motor area (M2), a region known to yield increased cell death following radiation27, 28. Limitations of the hd-MEA chips, however, did not allow us to record activity from slices afer imaging, hence it remains an open question whether these areas displayed aberrant neuronal activity.

Fig. 5. Neuronal complexity of cortical networks. Participation ratio (PR) in radiated slices (A). PR in slices treated with PE solution (B). Distribution of eigenvalues across experimental conditions ©.

Fig. 6. Propidium iodide (PI) staining of prefrontal slices following radiation. (A) Representative samples showing a graded increase in PI intensity with radiation dose. Arrow shows clustering of PI intensity at . Lef panel shows approximate location of secondary motor cortex (M2), Prelimbic cortex (PrL), medial orbital cortex (MO), ventral orbital cortex (VO), lateral orbital cortex (LO), and dorsolateral orbital cortex (DLO), (B) Mean PI intensity (“a.u.”: arbitrary units).

¶ Discussion

Tis study aimed to investigate the neuromodulatory efects of radiation on the fring rate, functional connectivity, complexity, and survival of PFC cells, and to compare the results with those obtained during epileptiform activity29. We found a marked increase in neuronal activity following acute doses of radiation2 , accompanied by an increase in complexity, as well as in the density and in some cases the strength of functional connectivity. Graph theoretic measures of functional connectivity including global efciency, assortativity, and transitivity were preferentially altered in radiated networks. Global synchronization was increased in high doses of radiation . Finally, radiation induced a dose-dependent cell death where damage was selectively localized to areas surrounding M2, a region particularly vulnerable to radiation damage27, 28.

Tese results were distinct from epileptiform activity, where complexity was markedly higher, and functional connections were strong but exhibited a lower density than radiated slices due to the restricted spatial focus of epileptic seizures. Diferences between radiated slices and epileptiform activity highlight clear distinctions between the efects obtained in these two conditions: while neuronal activity and complexity were elevated in both radiated and PE slices, functional connections were more widely spread in radiation than under PE treatment. Tis work proposes a novel assay to test the impact of clinically relevant doses of radiation15, 16 on neural dynamics and cellular apoptosis.

Past research has established that fring rate and cross-correlations can increase together30 making it difcult to separate the two. However, it is worth noting that these two markers do not always increase together. For instance, during epileptiform activity, fring rates and the mean strength correlations are elevated compared to radiated slices, yet the density of functional connections was markedly lower. Tis is explained by the fact that waves of epileptiform activity occupied a spatially delimited region of the array (Fig. 2B)17. In cortical networks, correlations are modulated by a balance of excitatory and inhibitory synaptic transmission, making them an intricate marker of activity across broad populations of neurons31.

Our fndings outlined a marked increase in complexity during epileptiform activity, compared to a more moderate increase in radiated slices relative to controls. Tese fndings can be understood in the following way. Te activity recorded from large groups of neurons exhibits a high degree of redundancy due to the covariation across many neurons32. Because of this redundancy, neural activity occupies a small area of dynamical space relative to the total number of activity patterns that could be produced, analogous to consistently rolling a or with a six-sided dice. Te PR aims to measure the size of the area occupied by neural activity, technically known as the dimensionality of the manifold. Tis dimensionality refects the degrees of freedom required to capture the covariation across neurons23, 25, 33, 34. If a single eigenvalue is sufcient to explain all of the variance in activity, the PR will yield a value of 1. Conversely, if many eigenvalues are required, the PR will approach a value corresponding to the number of neurons recorded. Our results indicate that both EP and radiation broadens the manifold of activity, resulting in less repeatable patterns over time.

Te efects of radiation on neural dynamics within PFC networks remain to be fully elucidated, with past literature showing increased fring rates2 , changes in synaptic morphology2, 7 , inhibited synaptic function and disruptions in synaptic plasticity4, 8 . To date, however, scant attention has been devoted to intra- or inter-areal functional connectivity. Further, much of the literature has focused on the efect of radiation on the hippocampus, leaving a growing need to study the PFC due to its involvement in the hippocampal-PFC pathway. Tis pathway is believed to play a key role in the cognitive defcits/impairments experienced following radiation2, 27, 35, 36. Moreover, the PFC has been identifed as one of the areas that are most sensitive to radiation27, 36, 37.

Given established links between functional connectivity and cognitive outcomes19, 20, 38, examining the efects of radiation on functional connectivity in reduced hd-MEA preparations is of critical importance to understanding the neurophysiological mechanisms of radiation-induced damage and their impact in clinical settings. Our fndings of a dose-dependent disruption in functional connectivity are aligned with human imaging studies showing altered functional connectivity among regions that receive radiation35, 39, 40, 41. In turn, higher doses of radiation are associated with worse long-term cognitive prognoses5 . Understanding the cellular origins of functional connectivity in healthy and radiated brain circuits provides a fruitful avenue to develop interventions that limit radiation-induced cognitive damage.

Because the current study focused on the acute efects of radiation, the timescale of alterations in activity and functional connectivity following radiation remains limited. In-vitro acute brain slices under standard experimental conditions have a typical lifespan of . As a result, this study was limited to a window of only a few hours post-radiation and could not examine early delayed or late delayed radiation-induced injuries3, 4 . Despite this limitation, it is reasonable to assume that a majority of the injuries induced by radiosurgery are acute in nature given that extremely high doses are delivered within a brief time period. Tese fndings are also consistent with previous investigations of the acute efects of radiation on PFC neurons2 . Further research on early and late delayed radiation-induced injuries suggests diferential efects based on the timescale following radiation whereby an initial increase in fring rate is eventually followed by a decrease in activity2, 6 . Similar results have been reported in human nasopharyngeal carcinoma patients43, showing an acute increase in local activity which was associated with a decrease in functional connections and higher levels of necrosis in the late-delayed stage.

Further work will be needed to investigate the intracellular mechanisms involved in radiation-induced alterations in neuronal activity, functional connectivity, and cellular apoptosis, as hd-MEAs are restricted to tracking extracellular voltage defections in the vicinity of cells. For example, ionic channel kinetics or patch clamp experiments may prove fruitful in determining why PFC neurons become hyperexcitable as these mechanisms are not accessible via hd-MEA recordings. Past research has shown acute downregulation in excitatory NR2A subunits of the -methyl-D-aspartate receptors (NMDAR) and increases in inhibitory gamma-aminobutyric acid receptors ), leading to changes in synaptic function and inhibiting long-term potentiation8 . It is unclear how these phenomena are linked to broader efects on neuronal networks such as alterations in the density and strength of functional connections. Simultaneous intra/extracellular recordings, though technically difcult, may ofer insights in this regard44, 45.

Given that hd-MEAs revealed markers of radiation-induced damage in neuronal activity and network interactions, it would be benefcial to examine the potential impact of pharmacological preconditioning in preventing these alterations. Past research has shown that pre-treating brain slices with memantine, an NMDAR antagonist8 or administering oral doses of epigallocatechin-3-gallate (EGCG), the main polyphenolic compound in green tea46, and Quercetin, a favonoid that is found in several vegetables and fruits47, can provide neuroprotective efects against radiation damage.

One limitation of hd-MEA recordings is that it is not logistically possible to deliver fractionated doses of radiation that are used in typical radiation therapy protocols. Although implantable in vivo arrays are available, there are signifcant concerns regarding the radiosensitivity of the hd-MEA platform. In addition, the use of anaesthetics during in vivo protocols is known to infuence brain activity and alter neuronal functioning48, 49, which may impact recordings. We opted for large single doses of radiation such as those used for stereotactic radiosurgery, pulsed high-dose-rate brachytherapy and certain hypofractionated palliative treatment protocols15, 16, 50. Tese doses also provided a benchmark to compare the efects of standard dose rates ) to ultrafast dose rates on various markers of neural activity and cell death.

Alternate dose ranges such as those below or above could be employed in future studies to determine whether the same neural dynamics and dose-dependent cellular apoptosis would be observed. Notably, doses above 60 Gy have been shown to produce radiation-induced necrosis (radionecrosis) and lesions in animal models6, 51; however, clinical studies have revealed radionecrosis in normal tissues exposed to doses as low as . Similar to these fndings, our results revealed that cell death occurred in a dose-dependent manner beginning at doses as low as Finally, future studies should examine diferent regions of the brain using the methods employed in this study to determine whether there are area-specifc impacts of these doses.

In conclusion, hd-MEAs revealed radiation-induced changes in broad networks of the PFC that were characterized by increased fring rates, higher complexity, disrupted functional connectivity, and dose-dependent apoptosis. Tese markers were distinct from those observed in hd-MEA recordings of epileptiform activity, thus showing that radiation does not merely induce an epileptic state. Tese results point to hd-MEAs as a novel and promising tool for studying the interactions of clinically relevant doses of radiation and potential targets for radioprotection.

¶ Methods Overview of electrophysiological data Collection

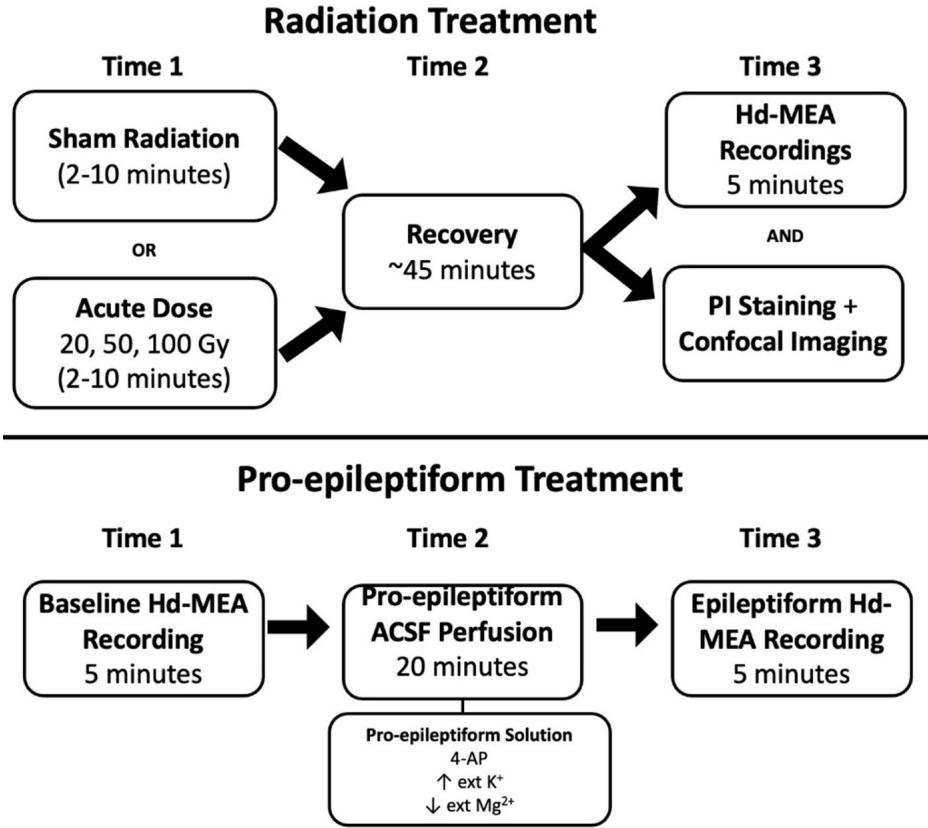

A total of 12 acute PFC slices were assigned to either the pro-epileptiform (PE, 2 slices) or radiation (10 slices) treatment (Fig. 7). Tis number is common for hd-MEA recordings as the statistical sample size is determined by the number of electrodes ) that are simultaneously recorded rather than the total number of slices. Fewer slices were analyzed for the pro-epileptiform treatment given that widespread ictal events constitute rare occurrences and were obtained from a previously published data set17. Slices receiving the PE treatment were frst recorded at baseline using the hd-MEA, then perfused with the PE solution and recorded again afer . Slices receiving the radiation treatment were split into control (4 slices) and radiated (6 slices) groups. Escalating radiation doses of 20 Gy, and 100 Gy were delivered to each of the slices followed by a 45-minute recovery period. Tese slices were then either recorded on the hd-MEA or imaged using propidium iodide (PI) staining.

Fig. 7. Illustration of the protocol employed to perform radiation, record neural activity, and apply PI staining to prefrontal cortical slices. A comparison of activity under radiation and PE treatment was performed.

Control slices received sham radiation followed by of recovery before proceeding to the recording or imaging step. Together, this platform provides a direct comparison between epileptiform- and radiation-induced changes in neural activity, as well as an evaluation of dose-dependent apoptosis.

¶ Animals

Data were collected using Sprague Dawley rats of both sexes, aged 14–21 days, purchased from Charles River. We chose to study juvenile animals as past research has shown that brain slices from juveniles attain higher survival rates than later developmental stages55. Te neurons in juvenile slices are also generally more resistant to various insults when compared to adult animals, suggesting that the efects reported in the juvenile slices may be even greater in mature animals56. Another motivating factor for studying juvenile rodents comes from agedependent fndings in human patients. Past research has shown an age-dependent efect of radiation whereby younger patients typically experience poorer outcomes than adult patients, thus highlighting the importance of studying these efects57. Tese fndings have also been replicated in rodent studies4 .

Animals were housed in standard housing conditions with cage enrichment and ad libitum access to water and standard chow. All experiments were carried out in accordance with Canadian Council on Animal Care Guidelines. All procedures were approved by the University of Ottawa Animal Care and Veterinary Services and comply with the ARRIVE guidelines.

¶ Acute slice preparation

Animals were deeply anaesthetized using isofurane (Baxter Corporation) and were subsequently euthanized via decapitation. Te brains of the animals were quickly extracted and submerged into a frozen choline dissection bufer. Te bufer consisted of the following: choline chloride, , , , 1.0 mM sodium ascorbate, glucose, NaHCO3, and was perfused with carbogen for prior to performing the dissection. Te brains were sliced coronally at a thickness of using a Leica VT1000S vibratome. Acute slices containing the PFC were used for all experiments. Due to the technological limitations of hd-MEA experiments, we were limited to performing a crude identifcation of the anatomical regions located within our slices. Given that we were unable to determine the exact anatomical localization of the slices, our goal was to understand the impact of radiation on PFC networks more broadly rather than provide localized efects of radiation on specifc regions of the PFC.

Once the slices were collected, they were placed in a recovery chamber flled with a standard artifcial cerebrospinal fuid (ACSF) consisting of the following: 119.0 mM NaCl, KCl, 2.5 mM , 1.0 1 , glucose, and . Te ACSF was continuously perfused using carbogen and maintained at a temperature of . Following slicing, brain slices were lef to recover for 1 h prior to experiments allowing the ACSF to equilibrate to room temperature.

¶ Radiation

Acute doses of radiation consisting of 20 Gy, 50 Gy, or were administered to a subset of healthy slices using the robotic radiosurgery platform (Cyberknife® G4) at a standard dose rate of . Te use of non-fractionated doses was selected to serve as a stepping stone for comparing standard dose rates to ultra-fast delivery methods such as FLASH radiation. Tese ultra-fast dose rates are several orders of magnitude greater than those used in conventional RT and have shown promise in maintaining the efcacy of the treatment while reducing radiation-induced injuries58, 59, 60, 61, 62. While acute PFC brain slices were continuously perfused with carbogen throughout the experiment, perfusion was temporarily halted while radiation doses were administered depending on the dose). Te radiation beam was in diameter and slices were placed in the center of the beam to ensure a homogeneous dose across the entire brain slice. Control slices were brought over to the same location as the Cyberknife to control for potential mechanical damage during transport. In addition, the carbogen perfusion was temporarily stopped for to mimic the experimental conditions. However, no radiation was delivered to these slices. Distinct slices were employed for radiation and controls given that hd-MEAs could not be radiated due to potential damage to the chips. Te slices in both conditions were then employed to either record neural activity or were stained with PI to quantify cell death.

¶ Epileptiform activity

We used a pro-epileptiform ACSF (PE-ACSF) containing the following: NaCl, NaH2PO4, MgSO4, 2 mM CaCl2, 24 mM NaHCO3, dextrose, and 4-AP to generate interictal-like neural activity29. In this condition, baseline recordings were taken from the same slices prior to the application of PE-ACSF. Following baseline recordings, slices were perfused in PE-ACSF for and 10-minute recordings of neural activity were collected. Te baseline slices difer slightly from the radiation control slices in that they were not exposed to the same potential mechanical damage caused by transporting the slices to be irradiated.

¶ Hd‑MEA recordings

System Description. Recordings of network-level neural activity were collected using an active pixel sensor hdMEA. Tis hd-MEA used a CMOS-based CCD monolithic chip in which the pixels were modifed to detect changes in electric voltages from electrogenic tissues. Te array provided simultaneous recordings from 4,096 electrodes with a sampling frequency of across the entire array. Te hd-MEA chips were comprised of electrodes arranged as a pixel element array whereby each pixel measures with an electrode pitch of . Te active area of the array was and had a pixel density of 567 pixels 63. Data were acquired using BrainWave sofware (3Brain Gmbh, Switzerland) and imported to MATLAB (MathWorks, Natick) for ofine analysis.

Hd-MEA Recording Protocol. A subset of acute PFC slices from each condition were placed on the hd-MEA chip, held in place by a harp and bathed in standard ACSF that was continuously perfused with carbogen ). Slices were maintained at a temperature of throughout the recording period. Recordings were completed in a dark environment to prevent interference from light artefacts. Five minutes of neural activity was recorded from each slice.

Quantifying Cell Death in Irradiated Brain Slices. A diferent subset of brain slices (4 slices) from each dose condition (20, 50, and ) and the control condition were subsequently stained using PI , Sigma–Aldrich), a cell death marker that binds to the DNA of neurons with fragmented plasma membranes but remains membrane impermeable in healthy neurons64. Following a 15-minute application of PI, serial dilution of the PI-stained ACSF was performed and acute brain slices were imaged using a Zeiss LSM880 confocal microscope. We quantifed cell death based on the mean intensity of images taken from PI-stained slices.

Data Preparation. Data collected from all conditions were initially processed using a second-order bandpass Butterworth flter in the forward and reverse directions ) applied to the raw voltages to remove high-frequency noise and slowly changing feld potentials65. Artefacts were identifed as any timepoint where the voltages were greater than Artefacts were subsequently replaced with the mean of the fltered data. Spike times were then extracted based on their multi-unit activity (MUA) using a voltage-threshold method66 whereby we identifed negative signal peaks below a threshold of 5 standard deviations (SD) from the mean of the fltered signal. To determine our fnal threshold, we frst calculated the mean and SD of the fltered baseline data and then took the diference between the two as our overall threshold. Tis fnal threshold was then applied to voltage data to identify multi-unit spike times, representing the activity of neurons within the vicinity of individual channels on the hd-MEA. A sample of the data and a MATLAB tutorial script is available as Supplementary Material.

A known limitation associated with MUAs is the possibility of capturing signal redundancies whereby a single channel picks up the activity from multiple neurons or a single neuron’s activity is picked up by multiple channels on the array67, 68, 69. Consequently, this method lacks the ground truth necessary to provide single-neuron resolution data. Despite this, broadband signals can be split into slower components that represent local feld potentials and faster components ) that constitute MUA or the sum of activity of the neurons in the vicinity of a single electrode . While inferential methods can be employed to sort the MUA into putative single-cell contributions67, 68, 6 9, a ground truth comparison is required to provide accurate spike sorting. Even in the absence of direct ground truth validation, studies have shown that MUAs capture key properties of activity in neural circuits and can be used to adequately infer fring rates and correlations amongst neurons75.

Neuronal Spike Rates. Spike times were employed to generate rasters that represent the activity of entire networks across time. Rasters were downsampled from to using non-overlapping temporal bins of binary data set to in the presence of one or more spikes, or if no spikes were present. We then computed a peri-stimulus time histogram using a rolling temporal window. A broad window of was used as spike rates were low. Channels without activity were removed from further analyses. Firing rates were assessed using a Kolmogorov-Smirnov test of normality which revealed non-normal distributions for all conditions . Past research has also established that cortical fring rate distributions follow a log-normal distribution rather than a normal distribution76, 77. As such, we opted to compare fring rates using a non-parametric Wilcoxon rank sum test (signifcance level: ), which assumes independence across samples but relaxes the assumption of Gaussian normality78. Finally, the use of a non-parametric test on global data distributions ensured that we did not overemphasize any minor efects that may have been amplifed given the substantial number of channels that were simultaneously recorded via the hd-MEA.

Functional Connectivity. Data were downsampled from to and a rolling window of was applied prior to computing Pearson correlations. Pearson cross-correlations were computed for each pair of electrodes within the hd-MEA, yielding a matrix of interactions. Tese correlations were subsequently passed through a threshold of to detect the presence or absence of a functional connection between pairs of channels, representing the statistical coincidence of multi-unit spikes at these channels. Data were assessed for normality using a Kolmogorov-Smirnov test followed by a Wilcoxon rank sum test.

Neural Complexity. Spatiotemporal patterns of activity recorded on the hd-MEA were described by their participation ratio (PR), a measure of neural complexity refecting the number of factors needed to capture fuctuations in the data23, 25, 33, 34. Te PR of population recordings was computed by frst extracting 10 brief time segments of data (mean duration: , SEM: 145.17) across each experimental condition. Te PR of each segment was computed by eigenspectrum decomposition79, providing ranked eigenvalues where denotes the total number of channels on the hd-MEA. Ten, the PR was calculated as the frst moment of the eigenspectrum normalized by the second moment,

If patterns of population activity can be described by a limited number of dimensions, only a portion of eigenvalues will be positive, resulting in a low PR. However, patterns of activity with higher complexity would yield a large number of positive eigenvalues and hence a higher PR.

¶ Data availability

Te data described in this study will be made available upon reasonable request to the corresponding author (J.P. Tivierge, jthivier@uottawa.ca). A Matlab tutorial (dx.doi.org/10.6084/m9.fgshare.26789953) and sample data (dx.doi.org/10.6084/m9.fgshare.26597269) are available online as a free resource.

Received: 11 June 2024; Accepted: 23 August 2024

Published online: 29 August 2024

¶ References

- Quigg, M., Rolston, J. & Barbaro, N. M. Radiosurgery for epilepsy: Clinical experience and potential antiepileptic mechanisms. Epilepsia 53(1), 7–15. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1528-1167.2011.03339.x (2012).

- Zhang, D. et al. Cranial irradiation induces axon initial segment dysfunction and neuronal injury in the prefrontal cortex and impairs hippocampal coupling. Neuro-Oncol Adv. 2(1), vdaa058. https://doi.org/10.1093/noajnl/vdaa058 (2020).

- Greene-Schloesser, D. et al. Radiation-induced brain injury: A review. Front. Oncol. 2, 73 (2012).

- Zhang, D. et al. Radiation induces age-dependent defcits in cortical synaptic plasticity. Neuro-Oncol 20(9), 1207–1214. https:// doi.org/10.1093/neuonc/noy052 (2018).

- Brière, M. E., Scott, J. G., McNall-Knapp, R. Y. & Adams, R. L. Cognitive outcome in pediatric brain tumor survivors: Delayed attention defcit at long-term follow-up. Pediatr. Blood Cancer 50(2), 337–340. https://doi.org/10.1002/pbc.21223 (2008).

- Zaer, H. et al. Non-ablative doses of focal ionizing radiation alters function of central neural circuits. Brain Stimulat. 15(3), 586–597. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brs.2022.04.001 (2022).

- Kempf, S. J. et al. Neonatal irradiation leads to persistent proteome alterations involved in synaptic plasticity in the mouse hippocampus and cortex. J. Proteome Res. 14(11), 4674–4686. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jproteome.5b00564 (2015).

- Wu, P. et al. Radiation induces acute alterations in neuronal function. PLOS ONE 7(5), e37677. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal. pone.0037677 (2012).

- Carlén, M. What constitutes the prefrontal cortex?. Science 358(6362), 478–482. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aan8868 (2017).

- Miller, E. K. & Cohen, J. D. An integrative theory of prefrontal cortex function. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 24(1), 167–202. https://doi. org/10.1146/annurev.neuro.24.1.167 (2001).

- Tierry, A. M., Gioanni, Y., Dégénétais, E. & Glowinski, J. Hippocampo-prefrontal cortex pathway: Anatomical and electrophysiological characteristics. Hippocampus 10(4), 411–419. https://doi.org/10.1002/1098-1063(2000)10:4<411::AID-HIPO7>3.0.CO;2-A (2000).

- Gould, J. Breaking down the epidemiology of brain cancer. Nature 561(7724), S40–S41. https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-018- 06704-7 (2018).

- Stevenson, I. H. & Kording, K. P. How advances in neural recording afect data analysis. Nat. Neurosci. 14(2), 2. https://doi.org/ 10.1038/nn.2731 (2011).

- Ferrea, E. et al. Large-scale, high-resolution electrophysiological imaging of feld potentials in brain slices with microelectronic multielectrode arrays. Front. Neural Circ. 6, 80 (2012).

- Redmond, K. J. et al. Tumor control probability of radiosurgery and fractionated stereotactic radiosurgery for brain metastases. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. 110(1), 53–67. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrobp.2020.10.034 (2021).

- Tuleasca, C., Vermandel, M. & Reyns, N. Stereotactic radiosurgery: From a prescribed physical radiation dose toward biologically efective dose. Mayo Clin. Proc. 96(5), 1114–1116. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mayocp.2021.03.027 (2021). circuits of the cerebral cortex. BMC Neurosci. 24(1), 22. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12868-023-00792-6 (2023).

- Craddock, R. C., Holtzheimer, P. E. III, Hu, X. P. & Mayberg, H. S. Disease state prediction from resting state functional connectivity. Magn. Reson. Med.62 (6), 1619–1628. https://doi.org/10.1002/mrm.22159 (2009).

- Konstantinou, N., Pettemeridou, E., Stamatakis, E. A., Seimenis, I. & Constantinidou, F. Altered resting functional connectivity is related to cognitive outcome in males with moderate-severe traumatic brain injury. Front. Neurol. 9, 1163. https://doi.org/10. 3389/fneur.2018.01163 (2019).

- Lang S et al. (2017) Functional connectivity in frontoparietal network: Indicator of preoperative cognitive function and cognitive outcome following surgery in patients with glioma. World Neurosurg.105, 913–922. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wneu.2017.05.149

- Wang, K. et al. Altered functional connectivity in early Alzheimer’s disease: A resting-state fMRI study. Hum. Brain Mapp. 28(10), 967–978. https://doi.org/10.1002/hbm.20324 (2007).

- Rubinov, M. & Sporns, O. Complex network measures of brain connectivity: Uses and interpretations. NeuroImage 52(3), 1059– 1069. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2009.10.003 (2010).

- Altan, E., Solla, S. A., Miller, L. E. & Perreault, E. J. Estimating the dimensionality of the manifold underlying multi-electrode neural recordings. PLOS Comput. Biol. 17(11), e1008591. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pcbi.1008591 (2021).

- Hu, Y. & Sompolinsky, H. Te spectrum of covariance matrices of randomly connected recurrent neuronal networks, p. 24, (2020).

- Litwin-Kumar, A., Harris, K. D., Axel, R., Sompolinsky, H. & Abbott, L. F. Optimal degrees of synaptic connectivity. Neuron 93(5), 1153–1164. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuron.2017.01.030 (2017) (.e7).

- Mazzucato, L., Fontanini, A. & Camera, G. L. Stimuli reduce the dimensionality of cortical activity. Front. Syst. Neurosci. 10, 11. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnsys.2016.00011 (2016).

- Hnilicová, P. et al. Anatomic and metabolic alterations in the rodent frontal cortex caused by clinically relevant fractionated wholebrain irradiation. Neurochem Int. 154, 105293. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuint.2022.105293 (2022).

- Ueno, H. et al. Region-specifc reduction of parvalbumin neurons and behavioral changes in adult mice following single exposure to cranial irradiation. Int. J. Radiat. Biol. 95(5), 611–625. https://doi.org/10.1080/09553002.2019.1564081 (2019).

- Postnikova, T. Y., Amakhin, D. V., Trofmova, A. M. & Zaitsev, A. V. Calcium-permeable AMPA receptors are essential to the synaptic plasticity induced by epileptiform activity in rat hippocampal slices. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 529(4), 1145–1150. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbrc.2020.06.121 (2020).

- de la Rocha, J., Doiron, B., Shea-Brown, E., Josić, K. & Reyes, A. Correlation between neural spike trains increases with fring rate. Nature 448(7155), 802–806. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature06028 (2007).

- Mazzoni, A. et al. On the dynamics of the spontaneous activity in neuronal networks. PLOS ONE 2(5), e439. https://doi.org/10. 1371/journal.pone.0000439 (2007).

- Cunningham, J. P. & Yu, B. M. Dimensionality reduction for large-scale neural recordings. Nat. Neurosci. 17(11), 1500–1510. https://doi.org/10.1038/nn.3776 (2014).

- Mazzucato, L., Fontanini, A. & Camera, G. L. Stimuli reduce the dimensionality of cortical activity. Front. Syst. Neurosci. 10(11), 11. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnsys.2016.00011 (2016).

- Hu, Y. & Sompolinsky, H. Te spectrum of covariance matrices of randomly connected recurrent neuronal networks with linear dynamics. PLoS Comput. Biol. 18, e1010327. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pcbi.1010327 (2022).

- , S. C. et al. Prognosis of hippocampal function afer sub-lethal irradiation brain injury in patients with nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Sci. Rep. 7(1), 14697 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-13972-2.

- Kovalchuk, A. & Kolb, B. Low dose radiation efects on the brain–from mechanisms and behavioral outcomes to mitigation strategies. Cell Cycle 16(13), 1266–1270 (2017).

- Kornev, M. A., Kulikova, E. A. & Kul’bakh, O. S. Te cellular composition of the cerebral cortex of rat fetuses afer fractionated low-dose irradiation. Neurosci. Behav. Physiol. 35(6), 635–638. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11055-005-0104-3 (2005).

- Hawellek, D. J., Hipp, J. F., Lewis, C. M., Corbetta, M. & Engel, A. K. Increased functional connectivity indicates the severity of cognitive impairment in multiple sclerosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 108(47), 19066–19071. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1110024108 (2011).

- Kovács, Á. et al. Changes in functional MRI signals afer 3D based radiotherapy of glioblastoma multiforme. J. Neurooncol 125(1), 157–166. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11060-015-1882-2 (2015).

- Ma, Q. et al. Radiation-induced functional connectivity alterations in nasopharyngeal carcinoma patients with radiotherapy. Med. (Baltim). 95(29), e4275. https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000004275 (2016).

- Mitchell, T. J. et al. Human brain functional network organization is disrupted afer whole-brain radiation therapy. Brain Connect. 10(1), 29–38. https://doi.org/10.1089/brain.2019.0713 (2020).

- Buskila, Y. et al. Extending the viability of acute brain slices. Sci. Rep. 4(4), 4. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep05309 (2014).

- Ding, Z. et al. Radiation-induced brain structural and functional abnormalities in presymptomatic phase and outcome prediction. Hum. Brain Mapp. 39(1), 407–427. https://doi.org/10.1002/hbm.23852 (2018).

- Dipalo, M. et al. Intracellular and extracellular recording of spontaneous action potentials in mammalian neurons and cardiac cells with 3D plasmonic nanoelectrodes. Nano Lett. 17(6), 3932–3939. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.nanolett.7b01523 (2017).

- Hamilton, F., Berry, T. & Sauer, T. Tracking intracellular dynamics through extracellular measurements. PLOS ONE 13(10), e0205031. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0205031 (2018).

- El-Missiry, M. A., Othman, A. I., El-Sawy, M. R. & Lebede, M. F. Neuroprotective efect of epigallocatechin-3-gallate (EGCG) on radiation-induced damage and apoptosis in the rat hippocampus. Int. J. Radiat. Biol. 94(9), 798–808. https://doi.org/10.1080/ 09553002.2018.1492755 (2018).

- Kale, A. et al. Neuroprotective efects of Quercetin on radiation-induced brain injury in rats. J. Radiat. Res. (Tokyo) 59(4), 404–410. https://doi.org/10.1093/jrr/rry032 (2018).

- Huang, Z. et al. Altered temporal variance and neural synchronization of spontaneous brain activity in anesthesia. Hum. Brain Mapp. 35(11), 5368–5378. https://doi.org/10.1002/hbm.22556 (2014).

- Sorrenti, V. et al. Understanding the efects of anesthesia on cortical electrophysiological recordings: A scoping review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22(3), 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms22031286 (2021).

- Yuan, H. et al. Efects of fractionated radiation on the brain vasculature in a murine model: Blood–brain barrier permeability, astrocyte proliferation, and ultrastructural changes. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. 66(3), 860–866. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrobp.2006.06. 043 (2006).

- Zaer, H. et al. Radionecrosis and cellular changes in small volume stereotactic brain radiosurgery in a porcine model. Sci. Rep. 10(1), 16223. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-72876-w (2020).

- Blonigen, B. J. et al. Irradiated volume as a predictor of brain radionecrosis afer linear accelerator stereotactic radiosurgery. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. 77(4), 996–1001. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrobp.2009.06.006 (2010).

- Korytko, T. et al. 12 Gy gamma knife radiosurgical volume is a predictor for radiation necrosis in non-AVM intracranial tumors. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. 64(2), 419–424. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrobp.2005.07.980 (2006).

- Reynolds, T. A., Jensen, A. R., Bellairs, E. E. & Ozer, M. Dose gradient index for stereotactic radiosurgery/radiation therapy. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. 106(3), 604–611. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrobp.2019.11.408 (2020).

- Lipton, P. et al. Making the best of brain slices: Comparing preparative methods. J. Neurosci. Methods 59(1), 151–156. https://doi. org/10.1016/0165-0270(94)00205-U (1995).

- Huang, S. & Uusisaari, M. Y. Physiological temperature during brain slicing enhances the quality of acute slice preparations. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 7, 48. https://doi.org/10.3389/fncel.2013.00048 (2013).

- Mulhern, R. K., Merchant, T. E., Gajjar, A., Reddick, W. E. & Kun, L. E. Late neurocognitive sequelae in survivors of brain tumours in childhood. Lancet Oncol. 5(7), 399–408. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(04)01507-4 (2004).

- Favaudon, V. et al. Ultrahigh dose-rate FLASH irradiation increases the diferential response between normal and tumor tissue in mice. Sci. Transl. Med. 6(245), 245ra93-245ra93. https://doi.org/10.1126/scitranslmed.3008973 (2014).

- Hughes, J. R. & Parsons, J. L. FLASH radiotherapy: Current knowledge and future insights using proton-beam therapy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 21(18), 18. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms21186492 (2020).

- Matuszak, N. et al. FLASH radiotherapy: An emerging approach in radiation therapy. Rep. Pract. Oncol. Radiother. 27(2), 2. https:// doi.org/10.5603/RPOR.a2022.0038 (2022).

- Montay-Gruel, P. et al. Irradiation in a fash: Unique sparing of memory in mice afer whole brain irradiation with dose rates above 100Gy/s. Radiother Oncol. 124(3), 365–369. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.radonc.2017.05.003 (2017).

- Simmons, D. A. et al. Reduced cognitive defcits afer FLASH irradiation of whole mouse brain are associated with less hippocampal dendritic spine loss and neuroinfammation. Radiother. Oncol. 139, 4–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.radonc.2019.06.006 (2019).

- Imfeld, K. et al. Large-scale, high-resolution data acquisition system for extracellular recording of electrophysiological activity. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 55(8), 2064–2073. https://doi.org/10.1109/TBME.2008.919139 (2008).

- Kuebler, E. S., Tauskela, J. S., Aylsworth, A., Zhao, X. & Tivierge, J. P. Burst predicting neurons survive an in vitro glutamate injury model of cerebral ischemia. Sci. Rep. 5(1), 1. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep17718 (2015).

- Bullmann, T. et al. Large-scale mapping of axonal arbors using high-density microelectrode arrays. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 13, 404. https://doi.org/10.3389/fncel.2019.00404 (2019).

- Lewicki, M. S. A review of methods for spike sorting: Te detection and classifcation of neural action potentials. Netw. Comput. Neural Syst. 9(4), R53-77 (1998).

- Hilgen, G. et al. Unsupervised spike sorting for large-scale, high-density multielectrode arrays. Cell Rep. 18(10), 2521–2532. https:// doi.org/10.1016/j.celrep.2017.02.038 (2017).

- Prentice, J. S. et al. Fast, scalable, Bayesian spike identifcation for multi-electrode arrays. PLOS ONE 6(7), e19884. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0019884 (2011).

- Rossant, C. et al. Spike sorting for large, dense electrode arrays. Nat. Neurosci. 19(4), 634–641. https://doi.org/10.1038/nn.4268 (2016).

- Bansal, A. K., Vargas-Irwin, C. E., Truccolo, W. & Donoghue, J. P. Relationships among low-frequency local feld potentials, spiking activity, and three-dimensional reach and grasp kinematics in primary motor and ventral premotor cortices. J. Neurophysiol.105(4), 1603–1619. https://doi.org/10.1152/jn.00532.2010 (2011).

- Davis, Z. W., Muller, L. & Reynolds, J. H. Spontaneous spiking is governed by broadband fuctuations. J. Neurosci. 42(26), 5159–

- https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1899-21.2022 (2022).

- Legatt, A. D., Arezzo, J. & Vaughan, H. G. Averaged multiple unit activity as an estimate of phasic changes in local neuronal activity: Efects of volume-conducted potentials. J. Neurosci. Methods 2(2), 203–217. https://doi.org/10.1016/0165-0270(80)90061-8 (1980).

- Mitzdorf, U. Current source-density method and application in cat cerebral cortex: Investigation of evoked potentials and EEG phenomena. Physiol. Rev. 65(1), 37–100. https://doi.org/10.1152/physrev.1985.65.1.37 (1985).

- Stark, E. & Abeles, M. Predicting movement from multiunit activity. J. Neurosci. 27(31), 8387–8394. https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUR OSCI.1321-07.2007 (2007).

- Trautmann, E. M. et al. Accurate estimation of neural population dynamics without spike sorting. Neuron 103(2), 292–308. https:// doi.org/10.1016/j.neuron.2019.05.003 (2019).

- Buzsáki, G. & Mizuseki, K. Te log-dynamic brain: how skewed distributions afect network operations. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 15(4),264–278. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrn3687 (2014).

- Song, S., Sjöström, P. J., Reigl, M., Nelson, S. & Chklovskii, D. B. Highly nonrandom features of synaptic connectivity in local cortical circuits. PLOS Biol 3, e68. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.0030068 (2005).

- Xia, Y. Chapter Eleven - Correlation and association analyses in microbiome study integrating multiomics in health and disease, In Progress in Molecular Biology and Translational Science, vol. 171, J. Sun, Ed., in Te Microbiome in Health and Disease, vol.171., Academic Press, pp. 309–491. doi: (2020). https://doi.org/10.1016/bs.pmbts.2020.04.003

- Chapin, J. K. & Nicolelis, M. A. L. Principal component analysis of neuronal ensemble activity reveals multidimensional somatosensory representations. J. Neurosci. Methods 94(1), 121–140. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0165-0270(99)00130-2 (1999).

¶ Acknowledgements

Tis work was supported by a Discovery grant to J.P.T. from the Natural Sciences and Engineering Council of Canada (NSERC Grant No. 210977) and the Gavin Murphy Research Fund (Ottawa Hospital Research Institute, University of Ottawa). Authors are thankful to the laboratory of Dr. Jean‐Claude Beïque (University of Ottawa) for infrastructure and technical support.

¶ Author contributions

M.B.R. and J.P.T. conceived the study. M.B.R. and J.S. performed the experiments and data collection. M.B.R. and J.P.T. analyzed the data. V.N. and J.P.T. supervised the study. All authors contributed to interpreting the results. All authors contributed to writing the manuscript.

¶ Competing interests

Te authors declare no competing interests.

¶ Additional information

Correspondence and requests for materials should be addressed to J.-P.T.

Reprints and permissions information is available at www.nature.com/reprints.

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional afliations.

Open Access Tis article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modifed the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. Te images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/ licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.