¶ Low glycemic index diet restrains epileptogenesis in a gender‑specifc fashion

Caterina Michetti1,3 · Daniele Ferrante1 Barbara Parisi1 Lorenzo Ciano1,3 · Cosimo Prestigio1 Silvia Casagrande1 · Sergio Martinoia2 · Fabio Terranova2 · Enrico Millo1 Pierluigi Valente1,4 · Silvia Giovedi’1,4 · Fabio Benfenati3,4 · Pietro Baldelli1,4

1 Department of Experimental Medicine, University of Genova, Genoa, Italy

2 Department of Informatics, Bioengineering, Robotics and System Engineering, University of Genova, Genoa, Italy

3 Center for Synaptic Neuroscience and Technology, Italian Institute of Technology, Genoa, Italy

4 IRCCS, Ospedale Policlinico San Martino, Genoa, Italy

Received: 18 July 2023 / Revised: 25 September 2023 / Accepted: 27 September 2023 / Published online: 10 November 2023

The Author(s) 2023

¶ Abstract

Dietary restriction, such as low glycemic index diet (LGID), have been successfully used to treat drug-resistant epilepsy. However, if such diet could also counteract antiepileptogenesis is still unclear. Here, we investigated whether the administration of LGID during the latent pre-epileptic period, prevents or delays the appearance of the overt epileptic phenotype. To this aim, we used the Synapsin II knockout (SynIIKO) mouse, a model of temporal lobe epilepsy in which seizures manifest 2–3 months after birth, ofering a temporal window in which LGID may afect epileptogenesis. Pregnant SynIIKO mice were fed with either LGID or standard diet during gestation and lactation. Both diets were maintained in weaned mice up to 5 months of age. LGID delayed the seizure onset and induced a reduction of seizures severity only in female SynIIKO mice. In parallel with the epileptic phenotype, high-density multielectrode array recordings revealed a reduction of frequency, amplitude, duration, velocity of propagation and spread of interictal events by LGID in the hippocampus of SynIIKO females, but not mutant males, confrming the gender-specifc efect. ELISA-based analysis revealed that LGID increased corticohippocampal allopregnanolone (ALLO) levels only in females, while it was unable to afect ALLO plasma concentrations in either sex. The results indicate that the gender-specifc interference of LGID with the epileptogenic process can be ascribed to a gender-specifc increase in cortical ALLO, a neurosteroid known to strengthen GABAergic transmission. The study highlights the possibility of developing a personalized gender-based therapy for temporal lobe epilepsy.

Keywords Epileptiform activity Glycemia Ketogenic diet Temporal lobe epilepsy Tonic GABAergic inhibition Sex efect -tetraidroprogesterone Syn2 Tonic–clonic

¶ Introduction

Epilepsy is one of the most common and serious chronic neurological diseases, afecting of the world population and characterized by spontaneous recurrent seizures. Seizures are the epiphenomenon of modifcations of neural circuits that, starting from an initial insult, become hyperexcitable during a latent process, named epileptogenesis. The initial insult activates multiple and complex cascades of events, lasting from hours to months, encompassing neurodegeneration, infammatory activity, transcriptional events, neurogenesis, sprouting, reorganization of neuronal circuits and gliosis [1, 2]. Using maladaptive mechanisms proper of neural plasticity, the epileptogenic process progressively alters neuronal excitability and modifes circuit connectivity before the frst seizure occurs [3]. In spite of the availability of a large toolbox of antiepileptic drugs (AEDs) capable of suppressing seizures, an anti-epileptogenic (AEG) strategy able to efciently contrast the epileptogenic process and prevent epilepsy is still on demand [4].

In the last 2 decades, several clinical trials based on the use of conventional AEDs for preventing epilepsy have been carried out, but the results have been unsuccessful or controversial, so that efective AEG drugs for treating people at risk are still missing [4, 5]. A possible explanation for this failure is that the molecular mechanisms of epileptogenesis difer from those of seizure manifestation. Seizures are a product of an overt excitatory/inhibitory imbalance, while epileptogenesis represents a complex cascade of events leading to the imbalance condition. AEDs act attempting to recover the balance producing an opposite imbalance elsewhere in the brain. On the contrary, to contrast epileptogenesis, it is probably more efcient a physiological strengthening of intrinsic homeostatic processes that normally defend neuronal networks from brains insults [6, 7]. Moreover, a preventive treatment for epilepsy with AEDs must be considered with caution in vulnerable patients showing markers of epileptogenesis associated with moderate probability of developing seizures, as in the case of cerebral malaria in which only of children presenting clear electrographic signs will develop epilepsy [8]. Thus, in people with uncertain probability of developing epilepsy, the risk of side efects due to treatment with conventional AEDs has to be considered, raising serious doubts on the opportunity of a treatment for preventive/protective purposes [4].

Metabolism-based therapies such as the traditional highfat, low-carbohydrate ketogenic diet (KD) and the much better tolerated, low-glycemic index diet (LGID) [9–11] may represent an alternative to prevent the development of epilepsy, because of their proven success in arresting drugresistant seizures [12, 13] coupled with the relative absence of side efects that allows chronic treatments in patients with uncertain risk of epilepsy, even in the pediatric age. More importantly, a large body of experimental evidence demonstrates that diet-based treatments activate multiple homeostatic mechanisms in the brain to increase seizure threshold [14–16] and make neuronal networks more resilient to stressors [17], thus preventing or reversing seizure progression [18–20]. Here, we studied the efcacy of LGDI in reverting the epileptogenic process in the Synapsin II knockout (SynIIKO) mice, an experimental model of monogenic refex temporal lobe epilepsy caused by dysfunctions of synaptic transmission.

The synapsins are a family of neuron-specifc phosphoproteins encoded by three distinct genes (Syn1, Syn2 and Syn3) that are abundantly expressed in the brain and concentrated in synaptic terminals where they act by regulating neurotransmitter release [21–25]. Large-scale search for genetic susceptibility loci in epilepsy identifed SYN2 as one of the fve major genes that contribute to epilepsy predisposition in humans [26]. These fndings were supported by subsequent studies, revealing that polymorphisms in SYN2 are associated with idiopathic generalized epilepsy [27–29]. Both SynIKO and SynIIKO mice show an epileptic phenotype, consisting of partial secondarily generalized tonic–clonic seizures, that is more severe in SynIIKO mice or in double SynI/SynIIKO mice [30–33]. Importantly, the behavioral seizures in SynIIKO mice are characterized by a late onset, thus ofering an operational window to test whether LGID modifes the epileptogenic process.

In the present work, SynIIKO mice fed with either LGID or standard diet (StD) during gestation and the postnatal life up to 5 months of age were investigated behaviorally for the appearance of epilepsy and electrophysiologically for the presence of interictal events in acute cortico-hippocampal slices. Behavioral and electrophysiological results revealed protective efects of LGID only in SynIIKO females. ELISAbased analysis revealed that LGID-fed female mice had higher cortical level of allopregnanolone (ALLO), a neurosteroid known as an agonist on GABAergic transmission, providing a mechanistic basis for the peculiar gender-specifc efect of LGID in this mouse model of temporal lobe epilepsy.

¶ Materials and methods

¶ Animals and diets

SynIIKO mice were generated by homologous recombination and extensively backcrossed on a C57BL/6 J background (Charles River, Calco, Italy) for over 10 generations [30, 34, 35]. Each homozygous SynIIKO female mouse was housed with one homozygous SynIIKO male in standard Plexiglas cages ), with sawdust bedding and a metal top. Female SynIIKO mice were split into two groups and fed ad libitum either StD or LGID starting from mating [36]). The two diets (Bio Serv, Flemington, NJ) were isocaloric , with the same nutritional profle (carbohydrate , protein , fat , fber , moisture ) and identical in micro- and macro-nutrients except for the type of starch, representing the main source of carbohydrate (Supplementary Table 1). The starch in the LGID was a combination of amylose and amylopectin (Hylon VII starch; Ingredion, Westchester, IL), whereas the starch in the StD was amylopectin (Amioca starch; Ingredion, Westchester, IL).

SynIIKO pregnant and lactating mothers and pups therefrom were fed ad libitum with either diet (Fig. 1A). After weaning, male (M) and female (F) ofsprings of each group of mothers were kept on the same diets as their mothers StD, M LGID, StD; F LGID). Sample size was chosen based on previous experience with behavioral seizures in SynIIKO mice [31]. Starting from weaning (P25), each mouse was weekly checked for body weight, food intake, water consumption and seizure onset. Blood glucose and glycated hemoglobin were assayed at 5 months of age (Fig. 1 and Supplementary Figs. 1–3). Mice were maintained on a light/dark cycle (lights on at 7 a.m.) at constant temperature and relative humidity . All experiments were carried out in accordance with the guidelines established by the European Communities Council (Directive 2010/63/ EU of March 4th, 2014) and were approved by the Italian Ministry of Health (authorization ).

¶ EXPERIMENTAL DESIGN

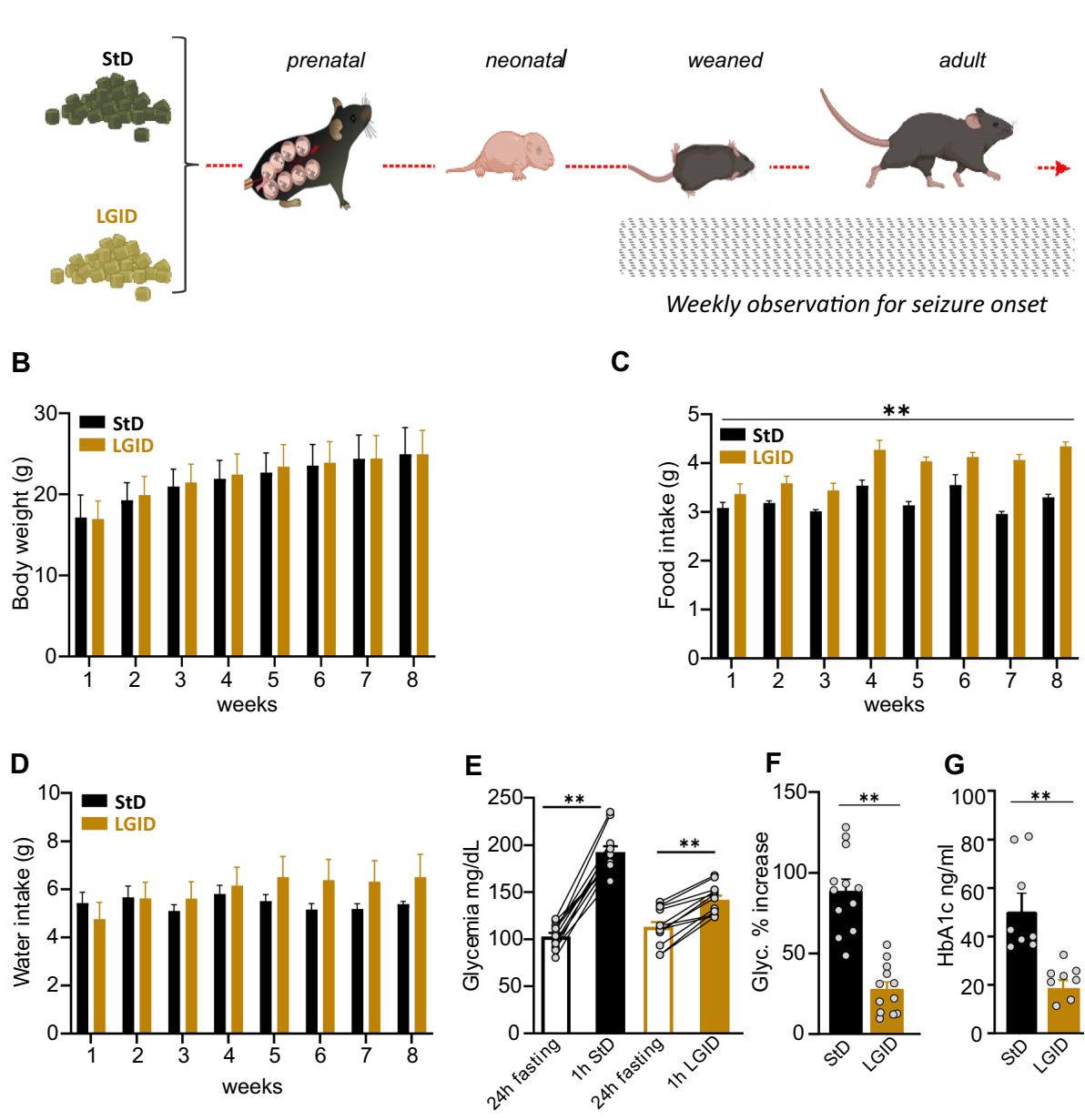

Fig. 1 Experimental plan and parameters analyzed during the administration of the two diets. A StD and LGID were delivered ad libitum to SynIIKO pregnant females starting from mating and continuing during pregnancy and lactation. Mice were maintained with LGID also after weaning and for the entire lifespan. Starting from the day of weaning, all mice were weekly checked for two months for body weight (B), food intake © and water consumption . Parameters analyzed in the two experimental groups revealed that LGID mice increased food consumption, although no diferences appeared in body weight and water consumption KO StD; KO LGID). Five months after birth all mice were subjected to blood analysis for the evaluation of glycemia and glycated hemoglobin

(G) levels. E For the analyses of blood glucose, mice were fasted for . Glycemia was measured immediately after the fasting period and after food administration. Glycemia levels showed a increase after food consumption in StD and LGID-fed mice for both StD and LGID). F Percentage increase of glycaemia observed 1 h after food administration for both StD and LGID). G Glycated hemoglobin levels were higher in StD-fed mice when compared with animals treated with LGID for both StD and LGID). Data are expressed as means . , ; two-way repeatedmeasures ANOVA (B–D), paired Student’s -test , unpaired Student’s -test , unpaired Mann–Whitney -test (G)

¶ Behavioral seizures

Seizure provocations were performed every frst day of the week (between 2 and ), starting from the day of weaning (P25), in acoustically isolated animal housing room. The provocation consisted of moving the animal from its cage to a new cage. The procedure started with opening the lid and lifting each mouse by its tail into an adjacent cage equipped with fresh bedding. This procedure is known to elicit refex seizures in SynIIKO mice [31–33, 35, 37]. All provocations were recorded on tape with a digital camera located in front of the new cage. Video recordings were later streamed to a PC for digital storage and detailed behavioral seizure analysis were made of-line. Due to the short time interval between seizure provocation and seizure generalization, we did not apply a severity score scale, but identifed the following three main elements of the seizure based on the previously described ethological description [31, 33]: (i) head and body myoclonic jerks, including retreating orofacial/forelimb twitch; (ii) whole tonic–clonic seizure (with or without jumping), including emprostoclonus, emprostotonus, epistotonus (iii) post-ictal immobility. The running ft activity was observed only in few animals and was not included in the analysis. Latency to the frst observed seizure (days from the date of birth), duration of each seizure, and percent of animals jumping were analyzed. At the end of behavioral follow-up, 5-month-old animals were sacrifced to collect blood samples and brains for biochemical and electrophysiological studies.

¶ Brain slice preparations

All experiments were performed on symptomatic (5 months of age) SynIIKO mice of either sex. Animals were anaesthetized with isofuoran prior to decapitation, the brain was quickly dissected out and immersed in an ice-cold oxygenated “cutting solution” composed of (mM): , 25 , 25 glucose, , 1.2 , , 2 , 0.4 ascorbic acid, 2 NaPyruvate, 3 myo-inositol, and saturated with . Transverse hippocampal slices thick) were cut using a Microm microtome equipped with a MicromCU65 cooling unit (Thermo Fisher Scientifc, Waltham, MA). Slices were cut at in a high-sucrose protective solution containing (in mM): , , , , , 25 glucose, 75 sucrose and saturated with . Slices were incubated for at and for at least another hour at room temperature in recording standard solution (artifcial cerebrospinal fuid, ACSF) composed of : , , 25 glucose, , 1.25 , , . Prior to being used for recordings slices were pre-incubated for in recording solution supplemented with 4-aminopyridine (4-AP; ; Sigma-Aldrich, Milan, Italy). Slices were then transferred to a “submerged” high-density multielectrode array (HDMEA) recording chamber which was continuously superfused at a rate of with ACSF supplemented with 4-AP . The bath temperature was monitored and maintained at throughout the experiments.

In accordance with the rare occurrence of spontaneous seizures in vivo, slices from Syn IIKO mice showed only sporadic spontaneous epileptiform activity under control perfusion conditions. The paucity of spontaneous paroxysms is also related to slice deaferentation and the submerged modality of MEA recordings. Thus, SynIIKO slices were perfused with the channel blocker 4-AP, a broad inhibitor of voltage-gated potassium channel subtypes [38–40], prolonging action potentials and thereby increasing neurotransmitter release at the presynaptic terminals [41]. 4-AP is widely used to cause epileptiform-like activity in in vitro and ex vivo preparations [42–45], as previously reported for SynIIKO hippocampal slices with respect to slices obtained from wild-type animals [37].

¶ HD‑MEA recordings of spontaneous epileptiform activity in brain slices

To record electrophysiological activity in brain slices, we used the Biocam X high-density CMOS-based multielectrode arrays (HD-MEA; 3Brain AG, Switzerland). The chip integrates amplifcation and analog multiplexing circuits that provide simultaneous extracellular recordings from 4096 electrodes (also called pixels) at a sampling rate of per channel. Each square pixel measures , and the array is integrated with an electrode pitch (centerto-center) of . Pixels are arranged in a array confguration, yielding an active area of with a pixel density of . Three on-chip amplifcation stages provide a global gain of , with a 0.1- to 5-kHz band-pass flter. This bandwidth is adapted to record both slow local feld potentials (LFPs) and fast action potentials (APs). Acquisition was controlled using the Brain Wave software (3Brain AG, Switzerland). Acute cortico-hippocampal slices were recorded for per session, once activity had stabilized for at least . Bath application of 4-AP [46] favored the induction of epileptiform activity characterized by spontaneous spikewave interictal discharges (I-ICs) that can be visualized as real-time video images in which each pixel of the video’s frames represents a recording-electrode of the array and has a color corresponding to the voltage amplitude according to a color-code map (see Supplementary Fig. 4B). Spike-wave complexes, usually lasting between 50 and , recorded by a single recording-pixel were named I-IC waves, while groups of I-IC waves that are temporally aggregated and recorded by an ensemble of spatially clustered pixels were named I-IC events.

I-IC waves were detected by the BrainWave software (3Brain AG) that adopts a previously described Precision Timing Spike Detection (PTSD) algorithm [47, 48] originally tailored to detect fast-spiking activity generated by cultured neurons and adapted to detect slower local feld potential events. To this purpose, the threshold was set to fvefold the standard deviation of the noise, whereas the refractory period and the peak lifetime period were set to 40 and , respectively. To evaluate the efects of the LGID on I-IC waves, amplitude (maximum value of the waveform modulus), duration (time an I-IC wave takes to extinguish) and energy (time integral of the I-IC wave modulus) were computed.

I-IC events were detected with a custom program written in Pyton (v3.7.1) that analyzes I-IC waves identifed by the BrainWave software. For the detection of I-IC events, we preliminarily evaluated the function representing the temporal aggregation of I-IC waves detected in each pixelchannel of a selected group (G):

as follows:

where is the number of I-IC waves in the interval and T the time window of integration. is computed at discrete time values t and represents how many I-IC waves are detected within the time window centered in t. I-IC events are detected applying a threshold on values and represent ensembles of temporally and spatially related I-IC waves in a specifc area of the corticohippocampal slice. I-IC events can be defned as an ensemble I-IC waves that are temporally and spatially related, representing the temporally synchronized activation of an aggregated of multiple neurons (i.e., recording-pixels) in a specifc area of the cortico-hippocampal slice. I-IC events are tracked in time and in space, to monitor their area and rate of propagation in the slice. To evaluate the efects of the LGID on I-IC events, we extracted the following features from the recordings: (i) afected area, as the ratio between the number of activated pixels/channels recording an I-IC wave and the total number of pixels/channels covering the cortical or hippocampal area; (ii) duration, as the time difference between the last and the frst I-IC wave of a detected event; frequency, as the number of I-IC events detected per min; covered distance and propagation speed, by analyzing the I-IC event propagation in space and in time. To capture the characteristics of propagation of the I-IC event occurring in the recording of the brain slice activity, a computer vision approach has been adopted. The developed algorithm is composed of two phases: video extraction and multiple object tracking (MOT). The software computes two diferent values: one is the average propagation speed, namely the weighted mean of the average speeds of each track, whose weights are the durations of each track trajectory; the second is the distance covered by the event, calculated as the sum of distances covered by each trajectory. All procedures used to detect and analyze I-IC events and waves were carried out blind to the experimenter thanks to algorithms based on custom programs written in Pyton (v3.7.1).

¶ Glycemia and glycated hemoglobin measurements

Blood glucose concentration was measured using a Mini Glucometer (Accu-Chek Aviva, Roche) by tail vein puncture of SynIIKO mice fed for 1 h with either StD or LGID after a fasting period. Glycemic index values were expressed as of blood sample. Glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) levels were measured in serum samples from the same animals using the HbA1c ELISA kit (mouse) (OKEH00661, Aviva System Biology, San Diego, CA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. All standards and samples were run in duplicate. The optical density values were read at in a multiplate reader (Tecan Infnite® F500, Tecan Trading AG, Switzerland). HbA1c concentrations were expressed as of blood sample.

¶ Brain allopregnanolone quantifcation

Cortico-hippocampal tissues from SynIIKO mice fed with either StD or LGID, were dissected after decapitation, immediately weighted and frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at until analysis. All females were at their diestrus stage according to vaginal cytology. An organic phase extraction with acetonitrile to solubilize steroids and hexane to remove fat and lipids was performed. Fifty mg of frozen samples were thawed on ice and homogenized in acetonitrile with a Tefon-glass homogenizer. After centrifugation at for at , the supernatant was carefully transferred to a clean glass tube, added with hexane and vigorously shaken. The organic phase was collected through a separatory funnel and the fat removal step was repeated twice. Acetonitrile was evaporated to dryness under a rotary evaporator (Rotavapor® R-100, BÜCHI Labortechnik AG, Switzerland) and successively in a concentrator centrifuge (VR-maxi St. a, Heto-Holten A/S, Denmark). Dried samples were frozen at and subsequently used for allopregnanolone (ALLO) quantifcation. ALLO concentrations were determined using the DetectX ALLO Immunoassay Kit (K044–H1, Arbor Assays, Ann Arbor, MI) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. After solubilization of dried steroids with a volume of ethanol followed by a volume of the kit Assay Bufer in a 1:4 (v:v) ratio, samples were vigorously shaken and allowed to sit at room temperature to ensure complete steroid solubilization. Reconstituted samples were immediately immunoassayed after bringing ethanol in the sample volume below with kit specifc Assay Bufer. All standards and samples were run in duplicate. The optical density values were read at in a multiplate reader (Tecan Infnite \textsuperscript { \textregistered } F500). ALLO concentration values were normalized on tissue weights and reconstitution volumes and expressed as pg/ mg of tissue weight.

¶ Statistical analysis

Data are given as means for sample size. The normal distribution of experimental data was assessed using D’Agostino-Pearson’s normality test. The -test was used to compare variance between two sample groups. To compare two normally distributed sample groups, the unpaired Student’s -test was used, with Welch’s correction applied in case the variance of the two groups was diferent. To compare two sample groups that were not normally distributed, the Mann–Whitney’s -test was used. To compare more than two normally distributed sample groups, we used oneANOVA, followed by the Tukey’s post hoc multiple comparison test. In case data were not normally distributed, oneway ANOVA was substituted with the Kruskal–Wallis’s test, followed by the Dunn’s post hoc multiple comparison test. Alpha levels for all tests were ( confdence intervals). Statistical analysis was carried out by using the Prism software (GraphPad Software, Inc.).

¶ Results

¶ Efects of LGID on general health and glycaemia

Breeding female SynIIKO mice were split into two groups and fed ad libitum either StD or LGID. The diet started with mating and continued during lactation and ofspring were fed the same diet after weaning for their entire life span (5 months). For 8 weeks starting from the day of weaning (25d), all ofspring mice (males and females) were weekly checked for body weight, food intake and water consumption (Fig. 1A–D). The measurements revealed a moderate but signifcant increase of food consumption in LGID-treated mice which was not accompanied by an increase in bodyweight or water consumption.

With the use of LGID, we expected to maintain low and stable levels of glycemia and to reduce glycemic peaks. For this reason, we measured glycemia and glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) in all SynIIKO mice 5 months after birth. To investigate the efects of the two diets on the post-prandial glycemic peak, glycemia was measured after a fasting period of and after food administration that immediately followed the fasting period (Fig. 1E, F). Fasting blood glucose levels showed similar values in StD and LGID treated mice, while food intake induced a signifcantly higher glucose level increase (percent increase vs fasting: ) in StDfed mice with respect to LGID-fed mice (percent increase vs fasting: ) (Fig. 1E, F). We also measured the levels of glycated hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) that integrates blood glucose levels over time [49] and consistently found that LGID-treated SynIIKO mice displayed a two-fold decrease in HbAc1 levels with respect to SynIIKO mice fed with StD (Fig. 1G).

¶ Sex‑dependent efect of LGID on behavioral seizures

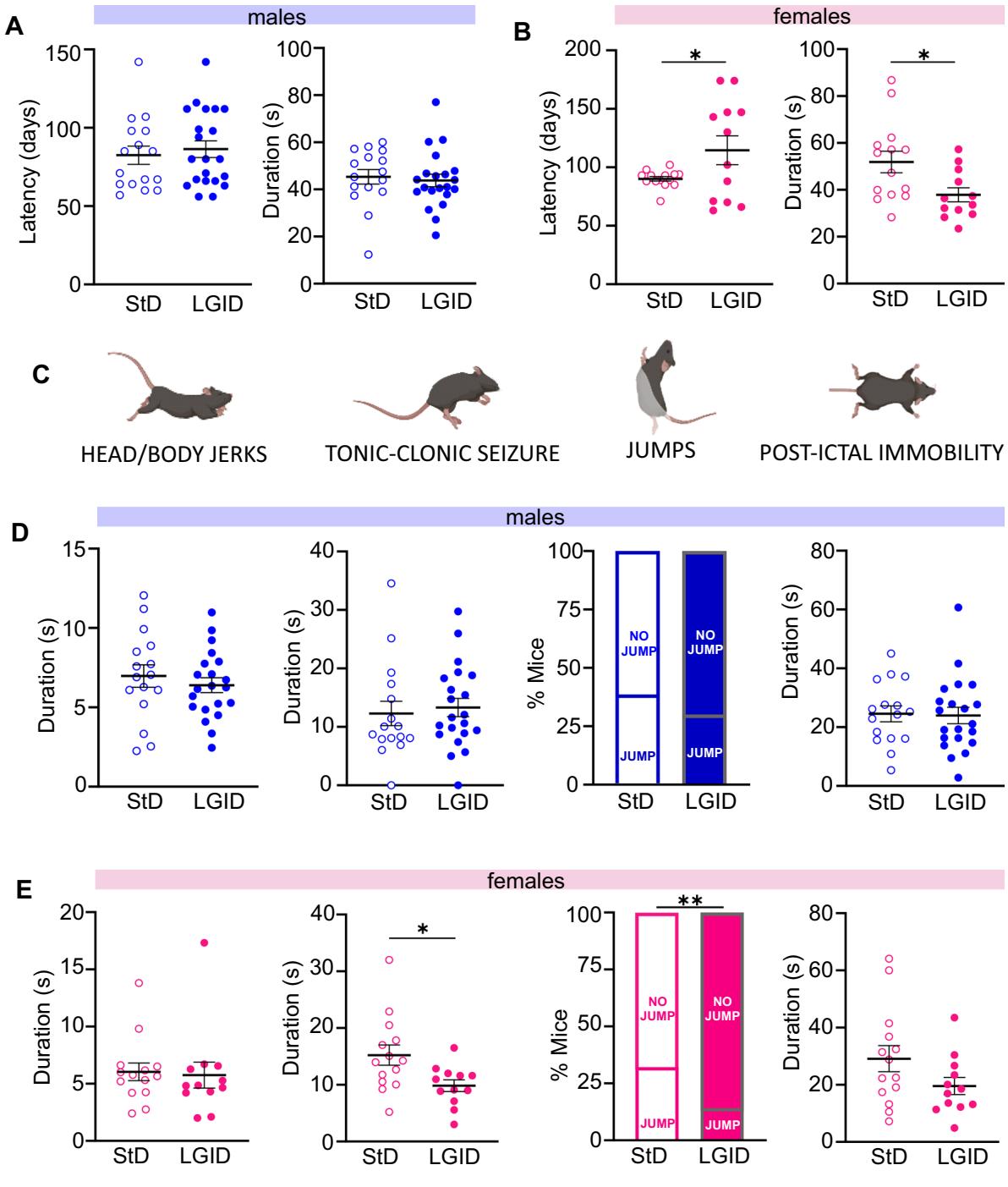

Behavioral seizures were tested weekly, starting from the day of weaning, manipulating the mice in an isolated environment and moving them to a new cage, a procedure known to efciently elicit refex seizures in SynIIKO mice [30, 31]). The latency to the frst seizure showed no diferences between the two experimental groups (Supplementary Fig. 1A), while the total seizure duration was signifcantly shorter in SynIIKO mice treated with LGID (Supplementary Fig. 1B). All mice experienced generalized seizures initiated by a frst short-lasting (5–15 s) phase of rapid muscle twitching afecting head, tail or legs (head and body myoclonus jerks, including retreating orofacial/forelimb twitch) (Supplementary Fig. 1C). The second phase consisted in typical tonic–clonic episodes with duration ranging between 5 and (Supplementary Fig. 1D) with jumps in about one third of the mice, generated by particularly intense clonic muscle contractions (Supplementary Fig. 1E). All seizures ended with a postictal immobility phase of variable duration, ranging from few seconds to one minute (Supplementary Fig. 1F). The various phases of the behavioral seizures were not afected by the diet when male and female data were pooled (Supplementary Fig. 1D–F). However, when male and female data were considered separately, a signifcant efect of LGID was observed only in females with longer latency to the frst seizure and decrease of total seizure duration (Fig. 2A, B). Similarly, a signifcant reduction of the duration of the tonic–clonic phase and of the percentage of jumping mice was observed in female, but not in male mice (Fig. 2D, E). The gender-specifc efcacy of LGID was not related to any sex-dependent diference in food or water consumption (Supplementary Fig. 2) or in the capability of LGID to decrease blood glucose or HbAc1 levels (Supplementary Fig. 3).

Fig. 2 Analysis of the frst observed seizure in male and female SynII KO mice. A, B Latency to the frst seizure and its duration in males (A) and females . No diferences in latency and duration of the frst seizure were observed in males, while the seizure onset was delayed and of reduced duration in female mice treated with LGID. C Representative images of the main seizure behaviors analyzed: head and body jerks, tonic–clonic attacks, jumping and post-ictal immobility. D, E Behavioral analysis of the seizures, including (from left to right): duration of head and body jerks, duration of tonic–clonic attacks, percentage of animals jumping during seizures and duration of post-ictal immobility. These parameters revealed a signifcant decrease in the duration of the tonic–clonic attacks and in the percentage of animals jumping only in females treated with LGID. Data are expressed as means sem M StD; M LGID; StD; LGID). , ; unpaired Student’s -test

¶ Sex‑dependent efects of LGID on neuronal excitability

I-IC discharges in cortico-hippocampal slices are considered a proxy of the epileptic phenotype [50] and have been already described in SynIIKO mice [37]. We investigated these bioelectrical markers of epilepsy in corticohippocampal slices obtained from symptomatic 5 months old SynIIKO mice of either sex treated with either LGID or StD. I-IC activity was analyzed by the HD-MEA system, that allows simultaneous extracellular recordings from 4096 electrodes at high spatial and temporal resolution (Supplementary Fig. 4A). The convulsant agent 4-AP ; [42]) was applied in the bath to favor the induction of epileptiform activity characterized by spontaneous spike-wave Inter-Ictal (I-IC) discharges. Cortical and hippocampal I-IC activity captured by the HD-MEA, can be visualized as a video, where each pixel of the video’s frames represents a recording-electrode of the array and the color of the pixel corresponds to the voltage amplitude detected by the recording pixel/electrode (Supplementary Fig. 4B). The spikewave complex, recorded by each recording pixel/electrode (Supplementary Fig. 4C) is an “I-IC wave”, while a group of “I-IC waves” that are temporally aggregated and recorded by an ensemble of spatially clustered pixels, represents an “I-IC event” (Supplementary Fig. 4D).

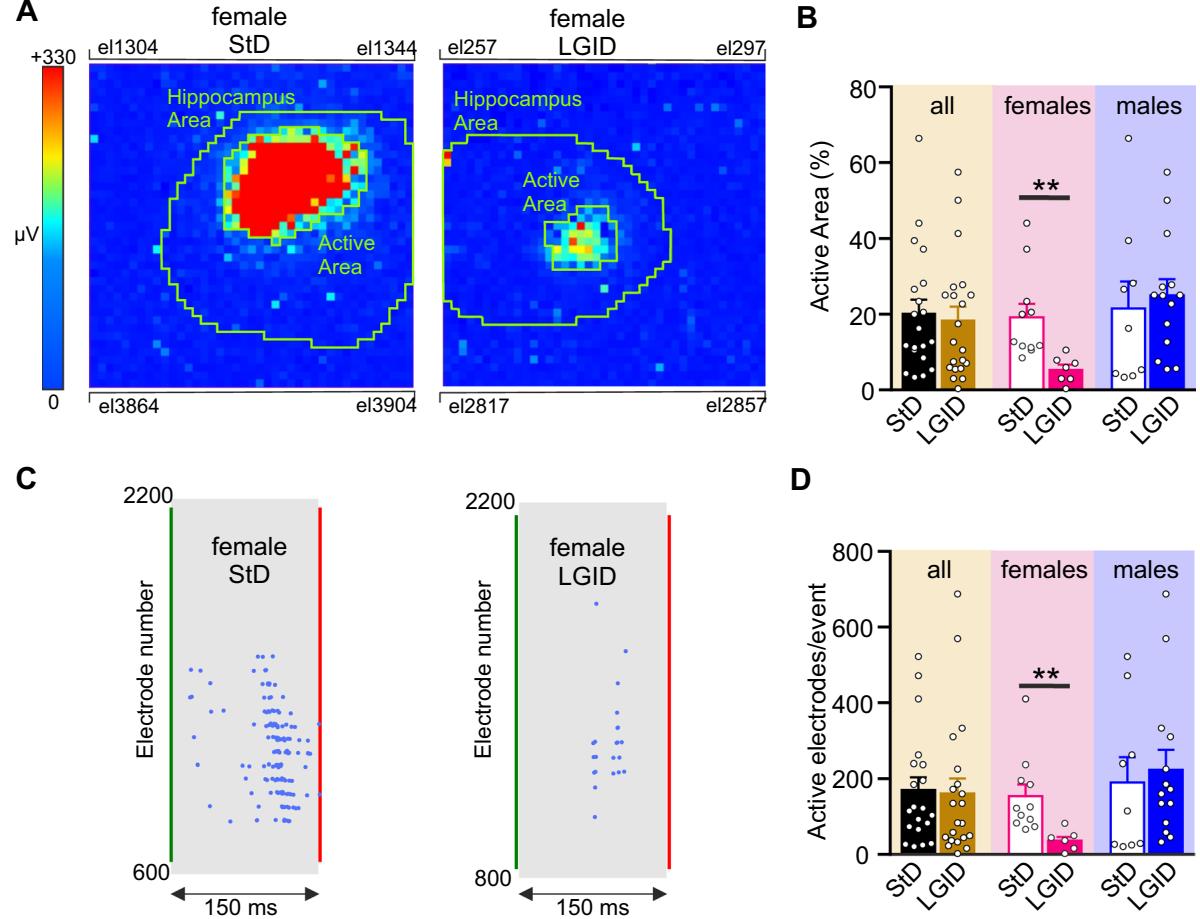

When all SynIIKO mice were compared, irrespective of sex, the percentage of hippocampal area invaded by an I-IC event, was not afected by the dietary condition. On the contrary, this parameter was dramatically reduced in LGDI-treated SynIIKO females and not afected in males treated with the same diet (Fig. 3A, B). Similar results were obtained when we quantifed the number of electrodes activated during an I-IC event in the hippocampal feld (Fig. 3C, D).

Fig. 3 Spatial constraint of I-IC events in the hippocampus of SynIIKO female mice treated with LGID. A Two video frames showing color-coded maps of two I-IC events activated in the hippocampal slice of two 5-month-old female SynIIKO mice treated with either StD (right panel) or LGID (left panel). The green lines delimit the hippocampal area. Pixel size: by side. B The bar plot shows means and individual values of the percentage areas of the hippocampus invaded by the I-IC events in all (left), female (center) and male (right) SynIIKO mice treated with either StD or LGID. C Raster plots of the two I-IC events shown in panel A. Single I-IC events recorded in the hippocampus of a female SynIIKO mouse

treated with either StD (left) or LGID (right). Each blue dot represents I-IC waves recorded by the pixel-electrodes. The green and red lines represent the start and the end of the I-IC event, respectively. D The bar plot shows means and individual values of the number of electrodes activated during an I-IC event in hippocampal slice of all (left), female (center) and male (right) SynIIKO mice treated with either StD or LGID ( and 21 for StD- and LGID-treated Syn II KO mice; and 7 for StD- and LGID-treated Syn II KO female mice; and 14 for StD- and LGID-treated Syn II KO male mice, respectively). ; unpaired Student’s -test

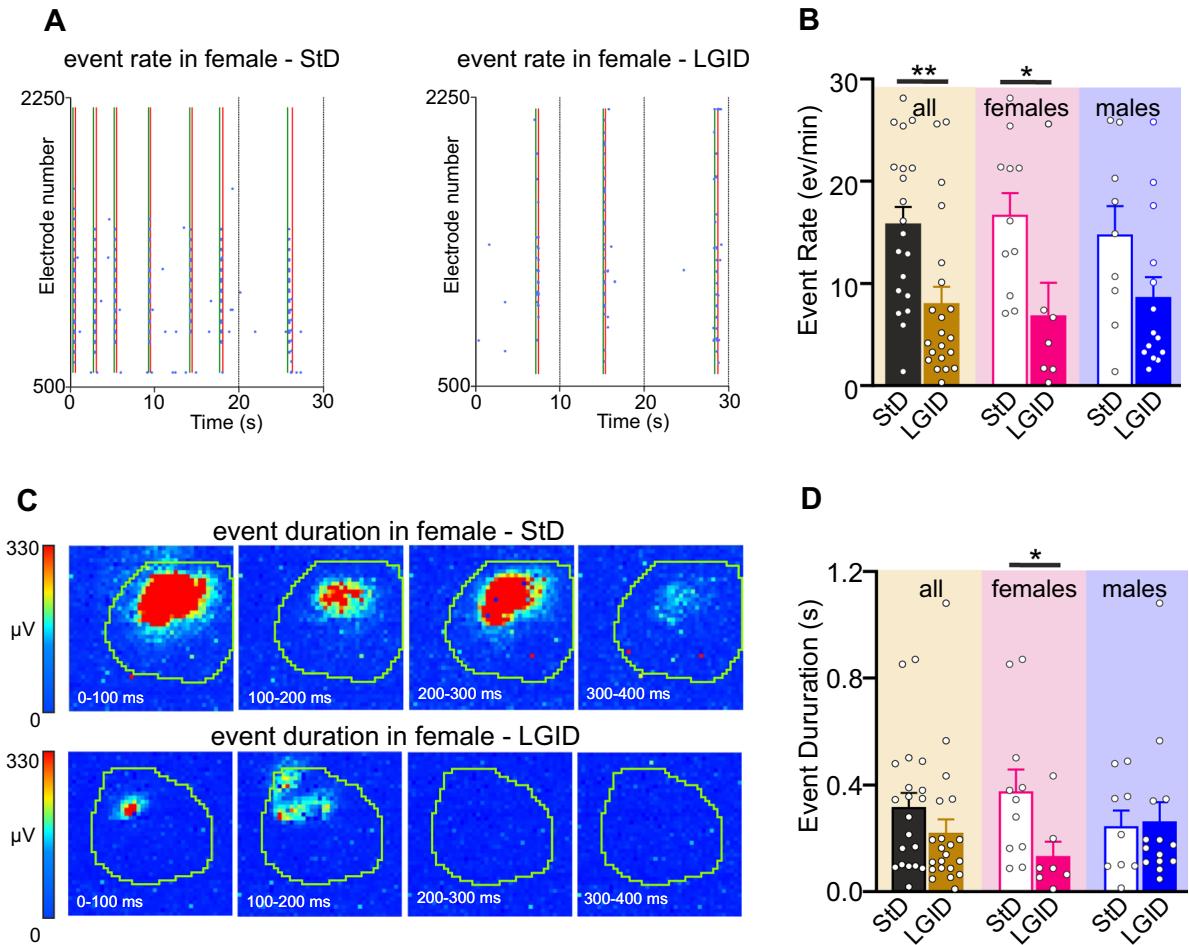

The frequency of hippocampal I-IC events was signifcantly reduced in the whole population of LGID-treated SynIIKO mice, regardless of sex. However, when this parameter was compared in sex matched mice, the reduction of I-IC rate induced by LGID remained signifcant only in females (Fig. 4A, B). Similarly, when the mean duration of hippocampal I-IC events was assessed in sexmatched or unmatched SynIIKO mice, LGID induced a signifcant and marked decrease of I-IC duration only in females (Fig. 4C, D).

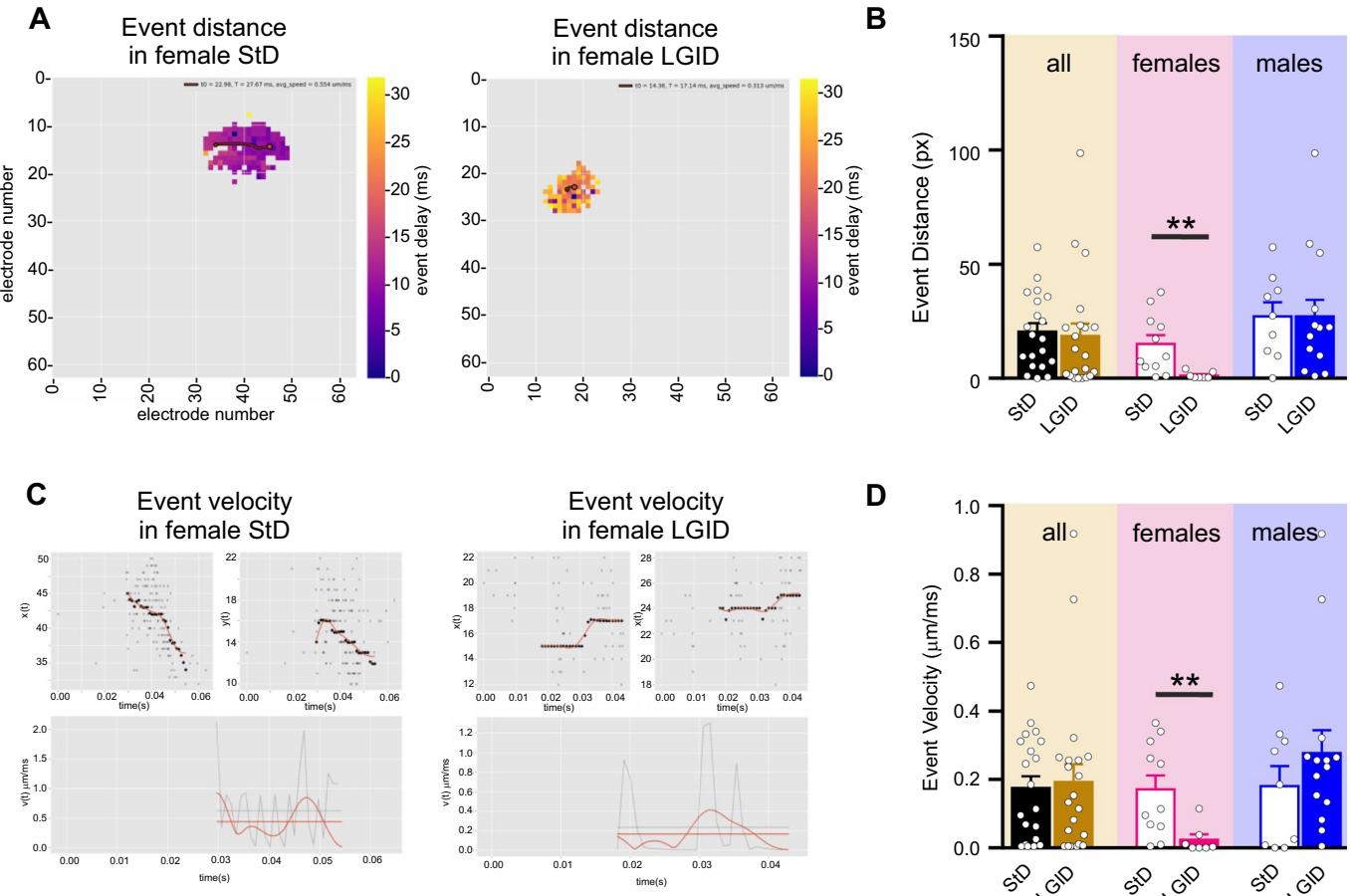

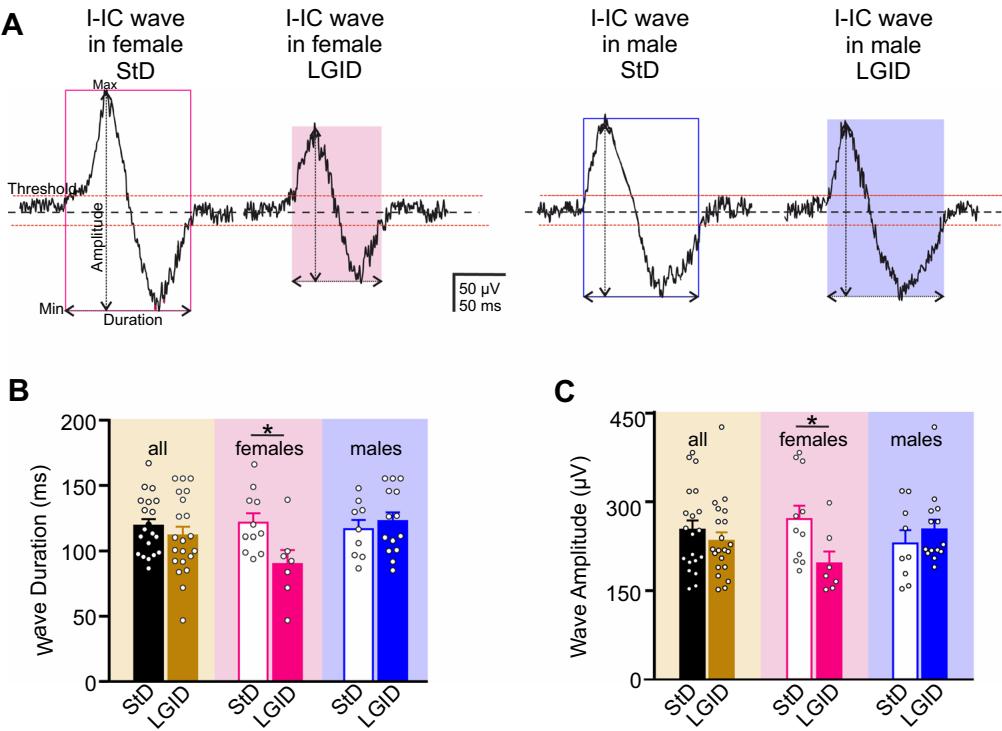

We also estimated the covered distance and propagation speed of each I-IC event idealized to a single “center of mass”. Also in this case, the distance and the velocity of the I-IC events were dramatically reduced by LGID treatment, but only in the female SynIIKO group (Fig. 5). Similar results were obtained when we measured the duration and amplitude of the spike-wave complexes (“I-IC waves”; Fig. 6A) that were again signifcantly reduced in duration and amplitude only in female SynIIKO mice treated with LGID (Fig. 6B, C).

HD-MEA recordings of cortical epileptiform activity highlighted a reduced efcacy of LGID with respect to the efects observed in the hippocampus. LGID was only efective in reducing the event rate, the event duration and the duration of the I-IC waves regardless of sex (Supplementary Fig. 5). However, when these parameters were compared in pocampal I-IC events recorded in two 5-month-old SynIIKO female mice treated with either StD (upper panels) or LGID (lower panels). Each color-code map is computed as the variation of amplitude in with the whole series that covers a time window of . Pixel size: by side. D The bar plot shows means and individual values of I-IC event duration in hippocampal slices of all (left), female (center) and male (right) SynIIKO mice treated with either StD or LGID and 21 for StD- and LGID-treated SynIIKO mice; and 7 for StD- and LGID-treated female SynIIKO mice; and 14 for StD- and LGID-treated male SynIIKO mice; respectively). , ; unpaired Student’s -test sex matched mice, the reduction of event and wave duration remained signifcant only in females, while it was lost in the male group.

Fig. 4 LGID reduces frequency and duration of hippocampal I-IC events in SynIIKO female mice. A Representative raster plots showing various I-IC events detected in a time window of in the hippocampus of two 5-month-old SynIIKO female mice treated with either StD (left panel) or LGID (right panel). The green and red lines represent the start and the end of the detected I-IC event, respectively. Each blue dot represents I-IC waves recorded by the pixel-electrodes. B The bar plot shows means and individual values of the I-IC event frequency in hippocampal slices from all (left), female (center) and male (right) SynIIKO mice treated with either StD or LGID. C The two series of video frames show color-code maps of two hip

Fig. 5 LGID reduces covered distance and propagation speed of hippocampal I-IC events in SynIIKO female mice. A The two video frames represent color-coded delay maps of two 5-month-old SynIIKO female mice treated with either StD (left panel) or LGID (right panel). The trajectory paths (in red) plotted over the delay map are used to calculate the distance covered by each I-IC event. The flled circle corresponds to the starting point of the trajectory. B The bar plot shows means and individual values of the distance covered by the I-IC event in hippocampal slices of all (left), female (center) and male (right) SynIIKO mice treated with either StD or LGID. C Upper panels show track trajectories of each I-IC event on the bidimensional plane of the chip, decomposed in its horizontal and vertical components, for two representative 5-month-old SynIIKO female mice treated with either StD (left panels) or LGID (right panels). Lower panels show the propagation speed (red horizontal line) of the I-IC event, calculated by averaging the smoothing (smooth red line) of instantaneous speed (gray jagged line) of each trajectory for two female mice treated with either StD (left panel) or LGID (right panel). D The bar plot shows means and individual values of the propagation speed of the I-IC events in hippocampal slices of all (left), female (center) and male (right) SynIIKO mice treated with either StD or LGID and 22 for StD- and LGID-treated SynIIKO mice; and 7 for StD- and LGID-treated female SynIIKO mice; and 14 for StD- and LGID-treated male SynIIKO mice; respectively). ; unpaired Student’s -test

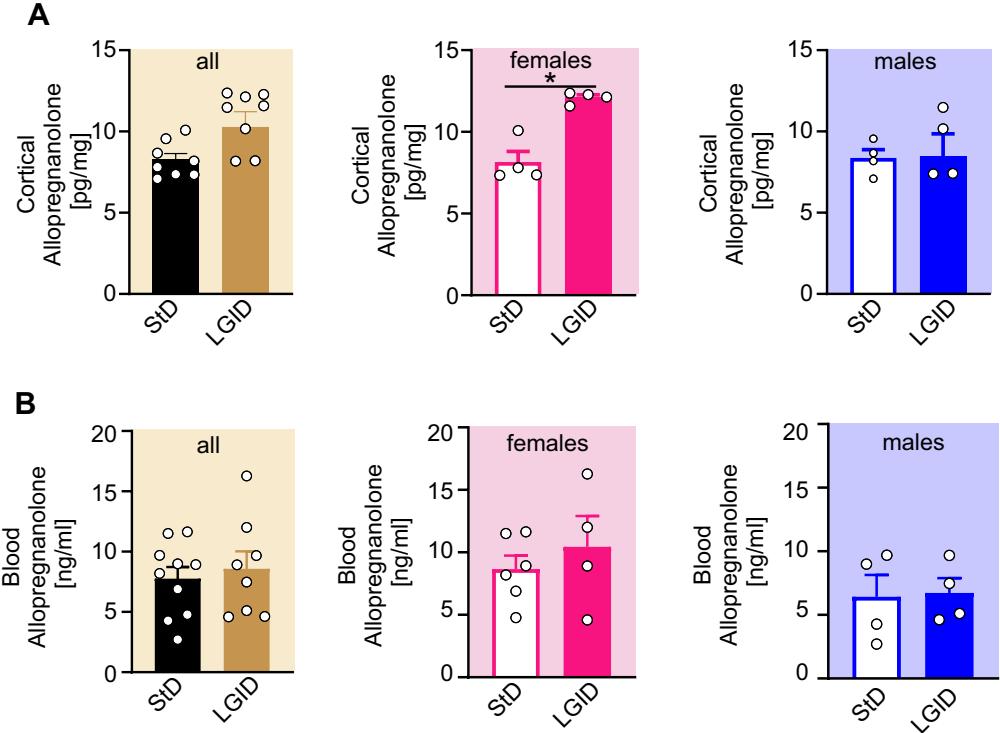

¶ Sex‑dependent efects of LGIDon cortico‑hippocampal allopregnanolone levels

Both behavioral and electrophysiological data revealed a gender-specifc protective action of LGID limited to SynIIKO females, suggesting a possible modulation of dietary treatment on the sex-related neurosteroid pathway. We focused our investigation on ALLO, well known for its anti-seizure action ascribed to a potent allosteric modulation on receptors [51, 52]. ELISA-based analysis on extracts of cortico-hippocampal tissue revealed an increase of ALLO concentration only in LGID-fed females, while the same efect was not present in LGIDtreated males (Fig. 7A). This effect was only present within the brain, as LGDI did not afect plasma ALLO levels regardless of gender (Fig. 7B).

Fig. 6 LGID reduces duration and amplitude of hippocampal I-IC either StD or LGID. C The bar plot shows means and indiwaves in SynIIKO female mice. A Representative electrophysiologi- vidual values of the I-IC wave amplitude in hippocampal slices of cal traces of I-IC waves recorded in the hippocampus of 5-month-old all (left), female (center) and male (right) SynIIKO mice treated with SynIIKO female (left) and male (right) mice treated with either StD either StD or LGID and 21 for StD- and LGID-treated Synor LGID as indicated. B The bar plot shows means and indi- IIKO mice; and 7 for StD- and LGID-treated female SynIIKO vidual values of the I-IC wave duration in hippocampal slices of all mice; and 14 for StD- and LGID-treated male SynIIKO mice; (left), female (center) and male (right) SynIIKO mice treated with respectively). ; unpaired Student’s -test

Fig. 7 LGID increases cortical ALLO concentration in female Syn II KO mice but not in male. A, The bar plots show means and individual values of ALLO concentrations in the cortico-hippocampal tissue (A) and plasma of all (left), female (center) and male (right) SynIIKO mice fed either StD or LGID and 8 for both StDand LGID-treated SynIIKO mice; for both StD- and LGID-treated female SynIIKO mice; for both StD- and LGID-treated male SynIIKO mice). ; unpaired Mann–Whitney -test

¶ Discussion

Despite decades of research activity, currently there is no FDA-approved treatment that truly prevents the development of epilepsy in people at risk. The negative results obtained using AEDs strongly impose a switch towards new strategies of intervention [4, 6, 53–55]. Most of the AEG-trials with AEDs aimed at preventing epilepsy following traumatic brain injury or stroke were unsuccessful also due to the heterogeneity of the patient populations [56]. The investigation of new strategies for the prevention of epilepsy could probably take advantage from the phenotypic homogeneity that characterizes genetic models of epilepsy, in which seizures occur either spontaneously or in response to sensory stimuli. The numerous genetic animal models of epilepsy characterized over the recent decades [57] have the advantage to simulate the vast majority of “idiophatic” epilepsy syndromes more closely than any other experimental model of epilepsy [58]. For these reason, to investigate the AEG action of LGID, we chose the SynIIKO mouse, a human monogenic epileptic synaptopathy, whose epileptogenic process was extensively characterized by us and others [25]. In this mouse, the deletion of SynII induces upregulation of synchronous release of GABA and a concomitant loss of delayed asynchronous release that are already present in pre-symptomatic mice. The lack of asynchronous GABA release impairs tonic inhibition due to the activation of GABAergic extrasynaptic receptors, in turn leading to an augmented fring activity at both single neuron and network levels [37, 59].

The history of dietary therapy for epilepsy is quite long, already Hippocrates documented the use of caloric restriction to treat epilepsy [60]. The ketogenic diet (KD) has been employed as a treatment for drug-resistant epilepsy for over 90 years [13]. Despite the substantial efcacy [61, 62], the use of KD remains limited because of difculties in implementation and tolerability. Recently, neuroscientists have proposed several antiepileptic treatment methods that involve metabolic regulation [15, 63, 64]. An efective alternative dietary approach is the LGID, which in many cases showed an efcacy comparable to the classic KD, but it is much better tolerated [9–12, 65, 66]. For this reason, LGID may better respond to the need of long-term preventive therapy to contrast epileptogenesis in healthy patients, often children, with high probability to develop epilepsy.

Here, we tested in vivo and ex vivo efects of the early application of LGID in SynIIKO mice starting from the prenatal phase. Behavioral characterization revealed that LGID produces a signifcant delay in the appearance of the frst seizure and a decrease of its duration. Surprisingly, this efect was observed only in females. The ex vivo electrophysiological investigation confrmed the genderdependent sensitivity by showing a decrease of evoked epileptic-like activity only in female SynIIKO mice fed with LGID. This specifc efect was not attributable to any gender-related diferences in food/water intake, body weight, blood glycemic index or glycated hemoglobin concentration.

What could be the mechanism of action for antiepileptogenic efect of LGID? Although dietary restrictions are widely used for the treatment of drug-resistant epilepsies, their mechanisms of action are still under investigation [5, 16]. Various studies have highlighted that the decrease of neuronal glucose utilization, obtained by diferent lowglucose diets such as KD, LGID or modifed Atkins diet or, alternatively, by glycolytic pathway inhibitors, such as 2-deoxy-glucose (2DG) represents the common mechanism at the basis of the antiepileptic action [14]. This hypothesis is further strengthened by the evidence that hyperglycemia lowers seizure threshold [5, 67] and infusion of glucose in patients under KD treatment results in restoration of the seizures [68]. Moreover, the anti-diabetic drug metformin is now recognized as a new potential AED or even AEG drug [69].

During the last 2 decades, at least three distinct mechanisms for the anti-seizure efects of low-glucose diets have been identifed [70]. It was initially reported that reduced glucose availability interferes with the membrane conductance of neurons, primarily via ATP-sensitive potassium channels that act as metabolic sensors coupling neuronal excitability to ATP levels [63, 71, 72]. Indeed, a reduction of cytoplasmatic ATP concentration has a hyperpolarizing efect mediated by channel opening [73]. More recently, it was shown that the transcriptional repressor REST/NRSF is activated by the reduced intracellular concentrations of NADH induced by the inhibition of glycolysis [15]. Such metabolic recruitment of REST/NRSF can induce the transcriptional repression of BDNF and its receptor TrkB [15] and activate other homeostatic pathways [74]. Indeed, REST/NRSF expression and translocation to the nucleus reduces neuronal fring [75], scales down excitatory inputs and potentiates inhibitory transmission onto excitatory neurons [76, 77]. More recently, it was also shown that REST/ NRSF boosts bufering and glutamate reuptake in astrocytes that are critical to maintain synaptic homeostasis [78].

Finally, several groups reported that 2DG-induced inhibition of glycolysis favors the synthesis of NADPH by enhancing the pentose phosphate pathway (PPP) in neurons [79–82]. PPP is the major source of NADPH in neurons [83] and is enhanced not only by 2DG, but also in case of reduced brain glucose availability [79], fasting [84, 85] or KD [86]. In these cases, glucose is redirected to the PPP, as shown by the increase of PPP metabolites, probably due to the increased demand for NADPH, aimed at strengthening antioxidant defense. NADPH acts as the crucial co-factor of -reductase (5α-R), the rate-limiting enzyme for ALLO biosynthesis [52, 87]. The N-terminal part of binds to steroid substrates, whereas the C-terminal portion containing a glycine-rich region binds NADPH [88]; consequently, a higher concentration of NADPH will increase neuronal ALLO production [89]. Also known as endogenous benzodiazepine, ALLO acts as a potent allosteric modulator of synaptic and extrasynaptic receptors and, therefore, enhances both phasic and tonic inhibition [90–92]. In particular, tonic inhibition, mediated by extrasynaptic receptors bearing subunits is specifcally sensitive to neurosteroids, and the resulting potentiation of tonic conductance favors a form of shunting inhibition that strictly controls neuronal network excitability and seizure susceptibility [93].

Given the pro-epileptogenic efect of the lack GABAergic tonic inhibition identifed in SynIIKO mice [37, 59], we focused on the increase in brain ALLO levels as the potential mechanism for the anti-epileptogenic action of LGID and for its gender-specifcity. We observed similar ALLO concentrations in the brain of male and female SynIIKO mice fed with StD, as previously reported in the brain of naïve rodents [94–96]. Notably, LGID treatment increased ALLO levels only in female cortico-hippocampal area, whilst the plasmatic concentration of ALLO was not afected by LGID in both sexes. These results suggested that the gender-specifcity of LGID is probably not related to changes of peripheral levels of ALLO but could derive from a sex-specifc increase of local synthesis of ALLO in the brain of SynIIKO females fed with LGID.

Our data on cortical ALLO, although still preliminary, indicate an avenue for future research. To fnd a mechanistic explanation for the LGID-induced increase of cortical ALLO production in females, it will be crucial to consider that: (i) female rodents have plasma and cortical progesterone (PROG) concentrations higher than males, irrespective of the phase of their estrous cycle [95, 97] and (ii) ALLO is synthesized in the brain from PROG by the sequential action of , which reduces PROG to -dihydroprogesterone ( -DHP) and -hydroxysteroid oxidoreductase ), which converts -DHP into ALLO [98]. Thus, PROG is the precursor of the enzymatic cascade, initiated and rate-limited by , that leads to ALLO biosynthesis in the brain [52].

Thus, future research activity will have the task of investigating whether, in females fed with LGID, the increase of NADPH concentrations potentiates the 5α-R activity and ALLO biosynthesis thanks to the higher PROG availability, an efect that in males can be greatly reduced or absent because of the limited availability of PROG.

Other causes of the gender specifcity, that deserve to be taken in consideration, are the possible sex diferences in activity and/or in the sensitivity of receptors to ALLO. Indeed, it was previously shown that the brain of female green anole lizards expresses higher levels of than males [99] and that female mice are more sensitive to the anti-epileptic efects of ALLO because of a greater abundance of δ-subunit containing extra-synaptic receptors [100].

The prevention of epilepsy is a relevant scientifc challenge and an urgent unmet need. In human genetic epilepsy, no treatment is available thus far able to prevent the development of epilepsy in patients at risk [3]. The investigation of the functional mechanisms underlying the homeostatic processes activated by the treatment with LGID represents a step forward for the identifcation of novel therapeutic solutions. The efcacy of LGID in delaying seizure onset in female mice suggest that this highly sustainable diet-based therapy is a promising strategy not only as an antiepileptic treatment, but to prevent or delay the appearance of the epileptic phenotype in syndromes with distinct etiology sharing similar evolution of the epileptogenic process. Finally, the greater protection of LGID observed in females, underlines the importance of developing personalized gender-specifc treatments.

Supplementary Information The online version contains supplementary material available at https://doi.org/10.1007/s00018-023-04988-1.

Acknowledgements We would like to acknowledge 3Brain field application scientist team for the fruitful discussion and support on the experiments performed with the Biocam X system. We thank Drs. Riccardo Navone and Diego Moruzzo (Istituto Italiano di Tecnologia, Genova, Italy) for help in the maintenance and genotyping of mouse strains.

Author contributions CM and LC performed behavioral experiments and behavioral data analysis, SC maintained and genotyped mouse strains and prepared diets; BP, EM and SG performed ELISA experiments and analysis; DF, CP, FT and PB performed and analyzed electrophysiological experiments; FT and SM developed Python scripts in collaboration with 3Brain software engineers; PB supervised the research; FB, CM and PB interpreted and discussed the data, prepared fgures, wrote the manuscript and funded research. All authors participated in data discussion and revised the manuscript.

Funding Open access funding provided by Università degli Studi di Genova within the CRUI-CARE Agreement. The study was supported by research grants from Compagnia di San Paolo Torino (2017.20612 to PB and 2019.34760 to FB); IRCCS Ospedale Policlinico San Martino (Ricerca Corrente and 5×1000’ to PB and FB); the Italian Ministry of University and Research (PRIN2017-A9MK4R to FB; #NEXTGENERATIONEU National Recovery and Resilience Plan (NRRP), project MNESYS PE0000006—A Multiscale integrated approach to the study of the nervous system in health and disease DN.

1553 11.10.2022 to SG and PB; 100008-2022 Curiosity Driven Grant founded by NEXT GENERATION EU to CM).

Data availability The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding authors on reasonable request.

¶ Declarations

Conflict of interest The authors have no relevant fnancial or non-fnancial interests to disclose.

Ethical approval All experiments were carried out in accordance with the guidelines established by the European Communities Council (Directive 2010/63/EU of March 4th, 2014) and were approved by the Italian Ministry of Health (authorization n° 600/2020-PR).

Consent to participate NA. The study does not involve any human subjects.

Consent to publish NA. The manuscript does not contain any individual person’s data.

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

¶ References

- Koepp MJ, Årstad E, Bankstahl JP, Dedeurwaerdere S, Friedman A, Potschka H, Ravizza T, Theodore WH, Baram TZ (2017) Neuroinfammation imaging markers for epileptogenesis. Epilepsia 58(Suppl 3):11–19. https://doi.org/10.1111/epi.13778

- Williams PA, Hellier JL, White AM, Staley KJ, Dudek FE (2007) Development of spontaneous seizures after experimental status epilepticus: implications for understanding epileptogenesis. Epilepsia 48:157–163. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1528-1167.2007. 01304.x

- Dichter MA (2009) Emerging concepts in the pathogenesis of epilepsy and epileptogenesis. Arch Neurol 66:443–447. https:// doi.org/10.1001/archneurol.2009.10

- Pawlik MJ, Miziak B, Walczak A, Konarzewska A, ChrościńskaKrawczyk M, Albrecht J, Czuczwar SJ (2021) Selected molecular targets for antiepileptogenesis. Int J Mol Sci 22:9737. https://doi. org/10.3390/ijms22189737

- Hartman AL, Stafstrom CE (2013) Harnessing the power of metabolism for seizure prevention: focus on dietary treatments. Epilepsy Behav EB 26:266–272. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yebeh. 2012.09.019

- Engel J, Pitkänen A (2020) Biomarkers for epileptogenesis and its treatment. Neuropharmacology 167:107735. https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2019.107735 7. Pitkänen A, Lukasiuk K (2011) Mechanisms of epileptogenesis and potential treatment targets. Lancet Neurol 10:173–186. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1474-4422(10)70310-0 8. Patel AA, Jannati A, Dhamne SC, Sapuwa M, Kalanga E, Mazumdar M, Birbeck GL, Rotenberg A (2020) EEG markers predictive of epilepsy risk in pediatric cerebral malaria –a feasibility study. Epilepsy Behav 113:107536. https://doi.org/10. 1016/j.yebeh.2020.107536

- Coppola G, D’Aniello A, Messana T, Pasquale FD, Della Corte R, Pascotto A, Verrotti A (2011) Low glycemic index diet in children and young adults with refractory epilepsy: frst Italian experience. Seizure - Eur J Epilepsy 20:526–528. https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.seizure.2011.03.008

- Grocott OR, Herrington KS, Pfeifer HH, Thiele EA, Thibert RL (2017) Low glycemic index treatment for seizure control in angelman syndrome: a case series from the center for dietary therapy of epilepsy at the Massachusetts general hospital. Epilepsy Behav EB 68:45–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yebeh.2016. 12.018

- Pfeifer HH, Lyczkowski DA, Thiele EA (2008) Low glycemic index treatment: implementation and new insights into efcacy. Epilepsia 49(Suppl 8):42–45. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1528- 1167.2008.01832.x

- Kim SH, Kang H-C, Lee EJ, Lee JS, Kim HD (2017) Low glycemic index treatment in patients with drug-resistant epilepsy. Brain Dev 39:687–692. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.braindev.2017. 03.027

- Haridas B, Kossof EH (2022) Dietary treatments for epilepsy. Neurol Clin 40:785–797. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ncl.2022.03. 009

- Fei Y, Shi R, Song Z, Wu J (2020) Metabolic control of epilepsy: a promising therapeutic target for epilepsy. Front Neurol. https:// doi.org/10.3389/fneur.2020.592514

- Garriga-Canut M, Schoenike B, Qazi R, Bergendahl K, Daley TJ, Pfender RM, Morrison JF, Ockuly J, Stafstrom C, Sutula T, Roopra A (2006) 2-Deoxy-D-glucose reduces epilepsy progression by NRSF-CtBP-dependent metabolic regulation of chromatin structure. Nat Neurosci 9:1382–1387. https://doi.org/10.1038/ nn1791

- Gasior M, Rogawski MA, Hartman AL (2006) Neuroprotective and disease-modifying efects of the ketogenic diet. Behav Pharmacol 17:431

- Masino SA, Rho JM (2019) Metabolism and epilepsy: ketogenic diets as a homeostatic link. Brain Res 1703:26–30. https://doi. org/10.1016/j.brainres.2018.05.049

- Freeman J, Veggiotti P, Lanzi G, Tagliabue A, Perucca E (2006) The ketogenic diet: from molecular mechanisms to clinical efects. Epilepsy Res 68:145–180. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eplep syres.2005.10.003

- Lusardi TA, Akula KK, Cofman SQ, Ruskin DN, Masino SA, Boison D (2015) Ketogenic diet prevents epileptogenesis and disease progression in adult mice and rats. Neuropharmacology 99:500–509. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuropharm.2015.08.007

- Masino SA, Rho JM Mechanisms of ketogenic diet action, In: J.L. Noebels, M. Avoli, M.A. Rogawski, R.W. Olsen, A.V. Delgado-Escueta (Eds.), Jaspers Basic Mech. Epilepsies, 4th ed., National Center for Biotechnology Information (US), Bethesda (MD), 2012. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK98219/ (Accessed 5 Jan 2023)

- De Camilli P, Benfenati F, Valtorta F, Greengard P (1990) The synapsins. Annu Rev Cell Biol 6:433–460. https://doi.org/10. 1146/annurev.cb.06.110190.002245

- Greengard P, Valtorta F, Czernik AJ, Benfenati F (1993) Synaptic vesicle phosphoproteins and regulation of synaptic function. Science 259(5096):780–785. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.84303 30

- Rosahl TW, Spillane D, Missler M, Herz J, Selig DK, Wolf JR, Hammer RE, Malenka RC, Südhof TC (1995) Essential functions of Synapsins I and II in synaptic vesicle regulation. Nature 375:488–493. https://doi.org/10.1038/375488a0

- Gitler D, Cheng Q, Greengard P, Augustine GJ (2008) Synapsin IIa controls the reserve pool of glutamatergic synaptic vesicles. J Neurosci Of J Soc Neurosci 28:10835–10843. https://doi.org/ 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0924-08.2008

- Cesca F, Baldelli P, Valtorta F, Benfenati F (2010) The Synapsins: key actors of synapse function and plasticity. Prog Neurobiol 91:313–348. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pneurobio.2010.04. 006

- Cavalleri GL, Weale ME, Shianna KV, Singh R, Lynch JM, Grinton B, Szoeke C, Murphy K, Kinirons P, O’Rourke D, Ge D, Depondt C, Claeys KG, Pandolfo M, Gumbs C, Walley N, McNamara J, Mulley JC, Linney KN, Shefeld LJ, Radtke RA, Tate SK, Chissoe SL, Gibson RA, Hosford D, Stanton A, Graves TD, Hanna MG, Eriksson K, Kantanen A-M, Kalviainen R, O’Brien TJ, Sander JW, Duncan JS, Schefer IE, Berkovic SF, Wood NW, Doherty CP, Delanty N, Sisodiya SM, Goldstein DB (2007) Multicentre search for genetic susceptibility loci in sporadic epilepsy syndrome and seizure types: a case-control study. Lancet Neurol 6:970–980. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1474-4422(07)70247-8

- Lakhan R, Kalita J, Misra UK, Kumari R, Mittal B (2010) Association of intronic polymorphism rs3773364 A>G in synapsin-2 gene with idiopathic epilepsy. Synapse 64:403–408. https://doi. org/10.1002/syn.20740

- Prasad DKV, Shaheen U, Satyanarayana U, Prabha TS, Jyothy A, Munshi A (2014) Association of GABRA6 (rs3219151) and Synapsin II (rs37733634) gene polymorphisms with the development of idiopathic generalized epilepsy. Epilepsy Res 108:1267–1273. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eplepsyres. 2014.07.001

- Fassio A, Raimondi A, Lignani G, Benfenati F, Baldelli P (2011) Synapsins: from synapse to network hyperexcitability and epilepsy. Semin Cell Dev Biol 22:408–415. https://doi.org/10. 1016/j.semcdb.2011.07.005

- Corradi A, Zanardi A, Giacomini C, Onofri F, Valtorta F, Zoli M, Benfenati F (2008) Synapsin-I- and Synapsin-II-null mice display an increased age-dependent cognitive impairment. J Cell Sci 121:3042–3051. https://doi.org/10.1242/jcs.035063

- Etholm L, Bahonjic E, Walaas SI, Kao H-T, Heggelund P (2012) Neuroethologically delineated diferences in the seizure behavior of Synapsin 1 and Synapsin 2 knock-out mice. Epilepsy Res 99:252–259. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2011.12.004

- Etholm L, Lindén H, Eken T, Heggelund P (2011) Electroencephalographic characterization of seizure activity in the Synapsin I/II double knockout mouse. Brain Res 1383:270–288. https:// doi.org/10.1016/j.brainres.2011.01.070

- Etholm L, Heggelund P (2009) Seizure elements and seizure element transitions during tonic-clonic seizure activity in the Synapsin I/II double knockout mouse: a neuroethological description. Epilepsy Behav EB 14:582–590. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yebeh. 2009.02.021

- Greco B, Managò F, Tucci V, Kao HT, Valtorta F, Benfenati F (2013) Autism-related behavioral abnormalities in synapsin knockout mice. Behav Brain Res 251:65–74. https://doi.org/10. 1016/j.bbr.2012.12.015

- Michetti C, Caruso A, Pagani M, Sabbioni M, Medrihan L, David G, Galbusera A, Morini M, Gozzi A, Benfenati F, Scattoni ML (2017) The knockout of Synapsin II in mice impairs social behavior and functional connectivity generating an ASD-like phenotype. Cereb Cortex NY N 1991(27):5014–5023. https://doi.org/ 10.1093/cercor/bhx207

- Currais A, Farrokhi C, Dargusch R, Goujon-Svrzic M, Maher P (2016) Dietary glycemic index modulates the behavioral and biochemical abnormalities associated with autism spectrum disorder. Mol Psychiatry 21:426–436. https://doi.org/10.1038/mp. 2015.64

- Medrihan L, Ferrea E, Greco B, Baldelli P, Benfenati F (2015) Asynchronous GABA release is a key determinant of tonic inhibition and controls neuronal excitability: a study in the Synapsin II-/- mouse. Cereb Cortex 25:3356–3368. https://doi.org/10. 1093/cercor/bhu141

- Stühmer W, Ruppersberg JP, Schröter KH, Sakmann B, Stocker M, Giese KP, Perschke A, Baumann A, Pongs O (1989) Molecular basis of functional diversity of voltage-gated potassium channels in mammalian brain. EMBO J 8:3235–3244. https://doi.org/ 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1989.tb08483.x

- Wulf H, Castle NA, Pardo LA (2009) Voltage-gated potassium channels as therapeutic targets. Nat Rev Drug Discov 8:982– 1001. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrd2983

- Coetzee WA, Amarillo Y, Chiu J, Chow A, Lau D, McCORMACK T, Morena H, Nadal MS, Ozaita A, Pountney D, Saganich M, De Miera EV-S, Rudy B (1999) Molecular diversity of channels. Ann N Y Acad Sci 868:233–255. https://doi.org/ 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1999.tb11293.x

- Nedergaard S (2000) Regulation of action potential size and excitability in substantia nigra compacta neurons: sensitivity to 4-aminopyridine. J Neurophysiol 82:2903–2913. https://doi. org/10.1152/jn.1999.82.6.2903

- Perreault P, Avoli M (1991) Physiology and pharmacology of epileptiform activity induced by 4-aminopyridine in rat hippocampal slices. J Neurophysiol 65:771–785. https://doi.org/ 10.1152/jn.1991.65.4.771

- Perreault P, Avoli M (1992) 4-aminopyridine-induced epileptiform activity and a GABA-mediated long-lasting depolarization in the rat hippocampus. J Neurosci Of J Soc Neurosci 12:104– 115. https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.12-01-00104.1992

- Heuzeroth H, Wawra M, Fidzinski P, Dag R, Holtkamp M (2019) The 4-aminopyridine model of acute seizures in vitro elucidates efficacy of new antiepileptic drugs. Front Neurosci 13:677. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnins.2019.00677

- Gonzalez-Sulser A, Wang J, Queenan BN, Avoli M, Vicini S, Dzakpasu R (2012) Hippocampal neuron fring and local feld potentials in the in vitro 4-aminopyridine epilepsy model. J Neurophysiol 108:2568–2580. https://doi.org/10.1152/jn.00363.2012

- Avoli M (1990) Epileptiform discharges and a synchronous GABAergic potential induced by 4-aminopyridine in the rat immature hippocampus. Neurosci Lett 117(1–2):93–98. https:// doi.org/10.1016/0304-3940(90)90125-s

- Ferrea E, Maccione A, Medrihan L, Nieus T, Ghezzi D, Baldelli P, Benfenati F, Berdondini L (2012) Large-scale, high-resolution electrophysiological imaging of feld potentials in brain slices with microelectronic multielectrode arrays. Front Neural Circuits 6:80. https://doi.org/10.3389/fncir.2012.00080

- Maccione A, Gandolfo M, Massobrio P, Novellino A, Martinoia S, Chiappalone M (2009) A novel algorithm for precise identifcation of spikes in extracellularly recorded neuronal signals. J Neurosci Methods 177:241–249. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jneum eth.2008.09.026

- Makris K, Spanou L (2011) Is there a relationship between mean blood glucose and glycated hemoglobin? J Diabetes Sci Technol 5:1572–1583

- Yang JC, Paulk AC, Salami P, Lee SH, Ganji M, Soper DJ, Cleary D, Simon M, Maus D, Lee JW, Nahed BV, Jones PS, Cahill DP, Cosgrove GR, Chu CJ, Williams Z, Halgren E, Dayeh S, Cash SS (2021) Microscale dynamics of electrophysiological markers of epilepsy. Clin Neurophysiol Of J Int Fed Clin Neurophysiol 132:2916–2931. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clinph.2021. 06.024

- Biagini G, Panuccio G, Avoli M (2010) Neurosteroids and epilepsy. Curr Opin Neurol 23:170–176. https://doi.org/10.1097/ WCO.0b013e32833735cf

- Diviccaro S, Ciof L, Falvo E, Giatti S, Melcangi RC (2022) Allopregnanolone: an overview on its synthesis and efects. J Neuroendocrinol 34:e12996. https://doi.org/10.1111/jne.12996

- Łukawski K, Andres-Mach M, Czuczwar M, Łuszczki JJ, Kruszyński K, Czuczwar SJ (2018) Mechanisms of epileptogenesis and preclinical approach to antiepileptogenic therapies. Pharmacol Rep 70:284–293. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pharep.2017. 07.012

- Radzik I, Miziak B, Dudka J, Chrościńska-Krawczyk M, Czuczwar SJ (2015) Prospects of epileptogenesis prevention. Pharmacol Rep PR 67:663–668. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pharep.2015. 01.016

- Ravizza T, Balosso S, Vezzani A (2011) Infammation and prevention of epileptogenesis. Neurosci Lett 497:223–230. https:// doi.org/10.1016/j.neulet.2011.02.040

- Löscher W, Klitgaard H, Twyman RE, Schmidt D (2013) New avenues for anti-epileptic drug discovery and development. Nat Rev Drug Discov 12:757–776. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrd4126

- Noebels JL (2003) Exploring new gene discoveries in idiopathic generalized epilepsy. Epilepsia 44:16–21. https://doi.org/10. 1046/j.1528-1157.44.s.2.4.x

- Stables JP, Bertram E, Dudek FE, Holmes G, Mathern G, Pitkanen A, White HS (2003) Therapy discovery for pharmacoresistant epilepsy and for disease-modifying therapeutics: summary of the NIH/NINDS/AES models II workshop. Epilepsia 44:1472–1478. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0013-9580.2003. 32803.x

- Medrihan L, Cesca F, Raimondi A, Lignani G, Baldelli P, Benfenati F (2013) Synapsin II desynchronizes neurotransmitter release at inhibitory synapses by interacting with presynaptic calcium channels. Nat Commun 4:1512. https://doi.org/10.1038/ ncomms2515

- Wheless JW (2008) History of the ketogenic diet. Epilepsia 49(Suppl 8):3–5. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1528-1167.2008. 01821.x

- Covey C (2021) Ketogenic diets for drug-resistant epilepsy. Am Fam Phys 103:524–525

- Martin-McGill KJ, Jackson CF, Bresnahan R, Levy RG, Cooper PN (2018) Ketogenic diets for drug-resistant epilepsy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 11:CD001903. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651 858.CD001903.pub4

- Giménez-Cassina A, Martínez-François JR, Fisher JK, Szlyk B, Polak K, Wiwczar J, Tanner GR, Lutas A, Yellen G, Danial NN (2012) BAD-dependent regulation of fuel metabolism and KATP channel activity confers resistance to epileptic seizures. Neuron 74:719–730. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuron.2012.03.032

- Sada N, Lee S, Katsu T, Otsuki T, Inoue T (2015) Epilepsy treatment. Targeting LDH enzymes with a stiripentol analog to treat epilepsy. Science 347:1362–1367. https://doi.org/10.1126/scien ce.aaa1299

- Miranda MJ, Turner Z, Magrath G (2012) Alternative diets to the classical ketogenic diet–can we be more liberal? Epilepsy Res 100:278–285. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2012.06.007

- Pfeifer HH, Thiele EA (2005) Low-glycemic-index treatment: a liberalized ketogenic diet for treatment of intractable epilepsy. Neurology 65:1810–1812. https://doi.org/10.1212/01.wnl.00001 87071.24292.9e

- Stafstrom CE (2003) Hyperglycemia lowers seizure threshold. Epilepsy Curr 3:148–149. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1535-7597. 2003.03415.x

- Huttenlocher PR (1976) Ketonemia and seizures: metabolic and anticonvulsant efects of two ketogenic diets in childhood epilepsy. Pediatr Res 10:536–540. https://doi.org/10.1203/00006 450-197605000-00006

- Singh R, Sarangi SC, Singh S, Tripathi M (2022) A review on role of metformin as a potential drug for epilepsy treatment and modulation of epileptogenesis, Seizure - Eur. J Epilepsy 101:253–261. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.seizure.2022.09.003

- Lutas A, Yellen G (2013) The ketogenic diet: metabolic infuences on brain excitability and epilepsy. Trends Neurosci 36:32– 40. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tins.2012.11.005

- Lutas A, Birnbaumer L, Yellen G (2014) Metabolism regulates the spontaneous fring of substantia nigra pars reticulata neurons via KATP and nonselective cation channels. J Neurosci Of J Soc Neurosci 34:16336–16347. https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUR OSCI.1357-14.2014

- Reid CA, Mullen S, Kim TH, Petrou S (2014) Epilepsy, energy defciency and new therapeutic approaches including diet. Pharmacol Ther 144:192–201. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pharmthera. 2014.06.001

- Nichols CG (2006) KATP channels as molecular sensors of cellular metabolism. Nature 440:470–476. https://doi.org/10.1038/ nature04711

- Lignani G, Baldelli P, Marra V (2020) Homeostatic plasticity in epilepsy. Front Cell Neurosci 14:197. https://doi.org/10.3389/ fncel.2020.00197

- Pozzi D, Lignani G, Ferrea E, Contestabile A, Paonessa F, D’Alessandro R, Lippiello P, Boido D, Fassio A, Meldolesi J, Valtorta F, Benfenati F, Baldelli P (2013) REST/NRSF-mediated intrinsic homeostasis protects neuronal networks from hyperexcitability. EMBO J 32:2994–3007. https://doi.org/10.1038/ emboj.2013.231

- Pecoraro-Bisogni F, Lignani G, Contestabile A, Castroflorio E, Pozzi D, Rocchi A, Prestigio C, Orlando M, Valente P, Massacesi M, Benfenati F, Baldelli P (2018) REST-dependent presynaptic homeostasis induced by chronic neuronal hyperactivity. Mol Neurobiol 55:4959–4972. https://doi.org/10.1007/ s12035-017-0698-9

- Prestigio C, Ferrante D, Marte A, Romei A, Lignani G, Onofri F, Valente P, Benfenati F, Baldelli P (2021) Rest/nrsf drives homeostatic plasticity of inhibitory synapses in a target-dependent fashion. Elife. https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.69058

- Centonze E, Marte A, Albini M, Rocchi A, Cesca F, Chiacchiaretta M, Floss T, Baldelli P, Ferroni S, Benfenati F, Valente P (2023) Neuron-restrictive silencer factor/repressor element 1-silencing transcription factor (NRSF/REST) controls spatial bufering in primary cortical astrocytes. J Neurochem. https://doi.org/10.1111/jnc.15755

- Cherkas A, Holota S, Mdzinarashvili T, Gabbianelli R, Zarkovic N (2020) Glucose as a major antioxidant: when, what for and why it fails? Antioxid Basel Switz 9:140. https://doi.org/10.3390/ antiox9020140

- Doiron B, Cuif MH, Chen R, Kahn A (1996) Transcriptional glucose signaling through the glucose response element is mediated by the pentose phosphate pathway. J Biol Chem 271:5321–5324. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.271.10.5321

- Stanton RC (2012) Glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase, NADPH, and cell survival. IUBMB Life 64:362–369. https:// doi.org/10.1002/iub.1017

- Stincone A, Prigione A, Cramer T, Wamelink MMC, Campbell K, Cheung E, Olin-Sandoval V, Grüning N-M, Krüger A, Tauqeer Alam M, Keller MA, Breitenbach M, Brindle KM, Rabinowitz JD, Ralser M (2015) The return of metabolism: biochemistry and physiology of the pentose phosphate pathway. Biol Rev Camb Philos Soc 90:927–963. https://doi.org/10.1111/brv.12140

- Herrero-Mendez A, Almeida A, Fernández E, Maestre C, Moncada S, Bolaños JP (2009) The bioenergetic and antioxidant status of neurons is controlled by continuous degradation of a key glycolytic enzyme by APC/C–Cdh1. Nat Cell Biol 11:747–752. https://doi.org/10.1038/ncb1881

- Kondoh H, Teruya T, Yanagida M (2020) Metabolomics of human fasting: new insights about old questions. Open Biol 10:200176. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsob.200176

- Teruya T, Chaleckis R, Takada J, Yanagida M, Kondoh H (2019) Diverse metabolic reactions activated during 58-hr fasting are revealed by non-targeted metabolomic analysis of human blood. Sci Rep 9:854. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-36674-9

- Peng F, Zhang Y-H, Zhang L, Yang M, Chen C, Yu H, Li T (2022) Ketogenic diet attenuates post-cardiac arrest brain injury by upregulation of pentose phosphate pathway-mediated antioxidant defense in a mouse model of cardiac arrest. Nutr Burbank Los Angel Cty Calif 103–104:111814. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. nut.2022.111814

- Melcangi RC, Ciof L, Diviccaro S, Traish AM (2021) Synthesis and actions of 5α-reduced metabolites of testosterone in the nervous system. Androg Clin Res Ther 2:173–188. https://doi.org/10. 1089/andro.2021.0010

- Wang M, Bhattacharyya AK, Taylor MF, Tai HH, Collins DC (1999) Site-directed mutagenesis studies of the NADPH-binding domain of rat steroid 5alpha-reductase (isozyme-1) I: analysis of aromatic and hydroxylated amino acid residues. Steroids 64:356– 362. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0039-128x(99)00010-0

- Pinna G, Rasmusson AM (2012) Upregulation of neurosteroid biosynthesis as a pharmacological strategy to improve behavioral defcits in a putative mouse model of PTSD. J Neuroendocrinol 24:102–116. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2826.2011.02234.x

- Farrant M, Nusser Z (2005) Variations on an inhibitory theme: phasic and tonic activation of GABAA receptors. Nat Rev Neurosci 6:215–229. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrn1625

- Nusser Z, Sieghart W, Somogyi P (1998) Segregation of diferent GABA receptors to synaptic and extrasynaptic membranes of cerebellar granule cells. J Neurosci 18:1693–1703. https://doi. org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-05-01693.1998

- Stell BM, Brickley SG, Tang CY, Farrant M, Mody I (2003) Neuroactive steroids reduce neuronal excitability by selectively enhancing tonic inhibition mediated by delta subunit-containing GABAA receptors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 100:14439–14444. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2435457100

- Carver CM, Reddy DS (2013) Neurosteroid interactions with synaptic and extrasynaptic GABA(A) receptors: regulation of subunit plasticity, phasic and tonic inhibition, and neuronal network excitability. Psychopharmacology 230:151–188. https://doi. org/10.1007/s00213-013-3276-5

- Gaignard P, Liere P, Thérond P, Schumacher M, Slama A, Guennoun R (2017) Role of Sex Hormones on Brain Mitochondrial Function, with Special Reference to Aging and Neurodegenerative Diseases. Front Aging Neurosci 9:406. https://doi.org/10. 3389/fnagi.2017.00406

- Gaignard P, Savouroux S, Liere P, Pianos A, Thérond P, Schumacher M, Slama A, Guennoun R (2015) Efect of sex diferences on brain mitochondrial function and its suppression by ovariectomy and in aged mice. Endocrinology 156:2893–2904. https://doi.org/10.1210/en.2014-1913

- Zhu X, Fréchou M, Liere P, Zhang S, Pianos A, Fernandez N, Denier C, Mattern C, Schumacher M, Guennoun R (2017) A role of endogenous progesterone in stroke cerebroprotection revealed by the neural-specifc deletion of its intracellular receptors. J Neurosci 37:10998–11020. https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUR OSCI.3874-16.2017

- Guennoun R (2020) Progesterone in the brain: hormone, neurosteroid and neuroprotectant. Int J Mol Sci 21:5271. https://doi. org/10.3390/ijms21155271

- Compagnone NA, Mellon SH (2000) Neurosteroids: biosynthesis and function of these novel neuromodulators. Front Neuroendocrinol 21:1–56. https://doi.org/10.1006/frne.1999.0188

- Cohen RE, Wade J (2010) Distribution of two isozymes of 5α-reductase in the brains of adult male and female green anole lizards. Brain Behav Evol 76:279–288. https://doi.org/10.1159/ 000322096

- Reddy DS, Matthew Carver C, Clossen B, Wu X (2019) Extrasynaptic GABA-A receptor-mediated sex differences in the antiseizure activity of neurosteroids in status epilepticus and complex partial seizures. Epilepsia 60:730–743. https://doi.org/ 10.1111/epi.14693

Publisher’s Note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional afliations.